Joe Harley is the producer and curator of the wildly successful Tone Poet reissue series. He’s been remastering and re-releasing classic Blue Note albums since 2019, which saw the 80th birthday of the iconic jazz label. For our expert chat, Joe was joined on Zoom by Darrel Sheinman, founder of the British jazz label and studio Gearbox. At one point, Sheinman happened to own one of the biggest collections of original Blue Note vinyl records worldwide.

Everything Jazz: How did you start collecting Blue Note records?

Darrel Sheinman: I’ve always been into jazz. I was actually a punk as a teenager. But you know, people say jazz is punk for older people, and that’s probably true. I just loved hard bop, then moving into post bop and funkier stuff. Blue Note covered that whole thing. Also, who can argue with that artwork? I would buy wherever I could and build up a large collection in the end.

Joe Harley: My mother was into jazz, and I became fascinated with drumming when I was around eight years old. I’d heard about this drummer “Philly“ Joe Jones. I thought his name was so hip. Anyway, I went to the small record store where I lived, in the middle of the country in Nebraska, and they had a small jazz section. They had a copy of “Cool Struttin“ by Sonny Clark. And there he was right on the cover: “Philly“ Joe Jones. I bought it and drove my parents crazy with that, on repeat over and over again, and I am on my little kit, trying to play along. And then, whenever I saw a Blue Note record, I would just buy it because I thought the covers were cool.

DS: That’s so interesting. I didn’t know you were a drummer. I’m a drummer too. I started at eight years old on Tupperware boxes, drumming along to The Police and David Bowie. My dad was also into jazz, he used to play Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five“.

JH: Now when people ask me if I’m a drummer, I always say no. And the reason is, as a teenager I became really close with Victor Lewis. When he left Nebraska, he went to New York, and within a week he was playing with Woody Shaw, Stan Getz and all those cats. When I heard Victor, I realised I’m just a poser. He belongs on one side of the glass in the studio, and I belong on the other.

EJ: What exactly is so special about the Blue Note records from the 1950s to the 1970s?

DS: Rudy van Gelder was quite an engineer. He was somewhat of a pioneer at the time. He had funny little techniques, like putting the microphone upside down with foam in the bottom of the bass, in the actual bridge of the bass. That made the bass sound really rich and warm. And that mattered a lot in the sound. It was all analog, which made it sound exceptional.

JH: These were recorded live to two-track. In other words, there’s no “fixing it in the mix“, no punch-ins. Rudy in effect became another member of the band, because he’s recording this as it’s going down live. And you hear him making moves, sometimes fairly radical moves. Lee Morgan comes in too close to the mic, and he’s coming in hot, and you can hear Rudy diving for the faders. In those days, the faders were rotaries, they weren’t sliders that we’re used to now. I don’t know how he did that, adjusting reverb on the fly, moving parts around. The technical challenges were substantial. Part of the quality comes from the simplicity. You’re eliminating a lot of electronics when you’re going live to two-track and not mixing. And then, very simple miking. For the longest time he had one mic on each individual player. Everything’s really tight, delays are short. You don’t have phase issues.

EJ: As an audiophile, what would you say makes the Tone Poet series so special?

DS: Purity! Keeping things as close to the original as possible. Like Joe was just explaining, the original tracking was very limited and dependent upon the sound of the room. So if the originals are good, you don’t need to do much else. You have to be able to produce a product that can adhere to that as best as possible. It’s when we muck around with things later in the post-production that things actually go wrong. I’m really pleased to see a series like Tone Poet doing things how they should be done. It’s how we would do it at Gearbox, if we ever got our hands on one of those original masters. From an audiophile point of view, it’s perfect.

JH: There is something pretty special about the analogue.

DS: A guy who used to make tape heads comes to buy original master copies off us in analogue. He’s a tape nerd, and he said that it has to do with slew rates, voltage limitation basically, which makes the analogue sound broader, richer, as well as compression on the tape. But a lot of people forget about this: if you’re listening on a rubbish system, it doesn’t make much difference.

EJ: Back in the day, most people didn’t own high-end stereo systems like audiophiles do nowadays. Do you take that into account?

JH: We master them with that expectation. When we started, our goal was to get them to sound as much like the originals as we could… that is until we went in for the first time and put up a master tape. This was a record we’d heard a million times, Horace Parlen’s “Speakin’ My Piece“. And we looked at each other like, “Holy cow! Wow, you can hear George Tucker’s bass. I don’t hear that on my original.“ So we changed our goal right there, which was to get what was on those masters, as opposed to trying to recreate the original LP. And it’s slightly controversial. Rudy really had to do things to keep those records sold. There’s no genuine low bass on those records. You didn’t want the record skipping. And he would use compression to make things pop a little more. Considering the systems of that time, it was kind of a genius move, because those records on that gear were really exciting to listen to. And they jumped in a way that a lot of other records didn’t. Anyway, cut to the present date, we assume that the user has much better gear, much more wide, full frequency response gear. And so we don’t do those things, we don’t use compression. I think Rudy, if he were around now and cutting vinyl, I suspect he would do the same. He wouldn’t have to make these compromises anymore.

DS: Funnily enough, I happened to speak to Rudy just before he passed away. I was such a geeky fan, and I found a number online, so I’d just call and he picked up. I started asking him questions, and he was quite happy to chat. He was really into CDs at that moment. Which is interesting, such an analogue guy. I asked him, “Why is that?“ And he was like, “Because I don’t have to worry about the dynamic range.“

JH: Exactly. But you know, there also are collectors that don’t care. They want those originals and they’ll pay for them. And I’m totally cool with however you get to the music. Whatever doorway speaks to you is certainly fine with me, as long as you got there, you know?

DS: Do you actually know a lot about the demographic that’s buying the Tone Poet records?

JH: It’s much younger than you might think. If you go to the chatrooms and whatnot, it’s mostly people that look like me and worse, but the peak of the demographic is between 35 and 50. When I go to the record stores, I’m almost always the oldest guy there. Which I love. There’s nothing better than hearing all these people in the jazz section flipping through and buying records, and they’re all younger than me. I love it. Somewhere on YouTube, these two guys were going on about one of the Jazz Messengers LPs, and they looked like they’re 14 to me. They were probably 20 and going on about the Jazz Messengers. That just made my day. How cool is this?

DS: Yeah, my 14-year old kid really likes his hip-hop. He was listening to Gang Starr’s “Jazz Thing“ the other day, asking me about all these players that they’re referring to in that track. I think it must have sort of come into his TikTok environment. But once he heard it, he was asking questions: “Who’s John Coltrane? Who’s this? Who’s that?“ Now we’ve been playing some Blue Notes. He listens for five minutes, then goes back to his hip-hop, but that’s okay.

JH: We’ll take it!

EJ: As the curator of the Tone Poet series, how do you actually decide on what will be the next batch of records that you’re gonna work on?

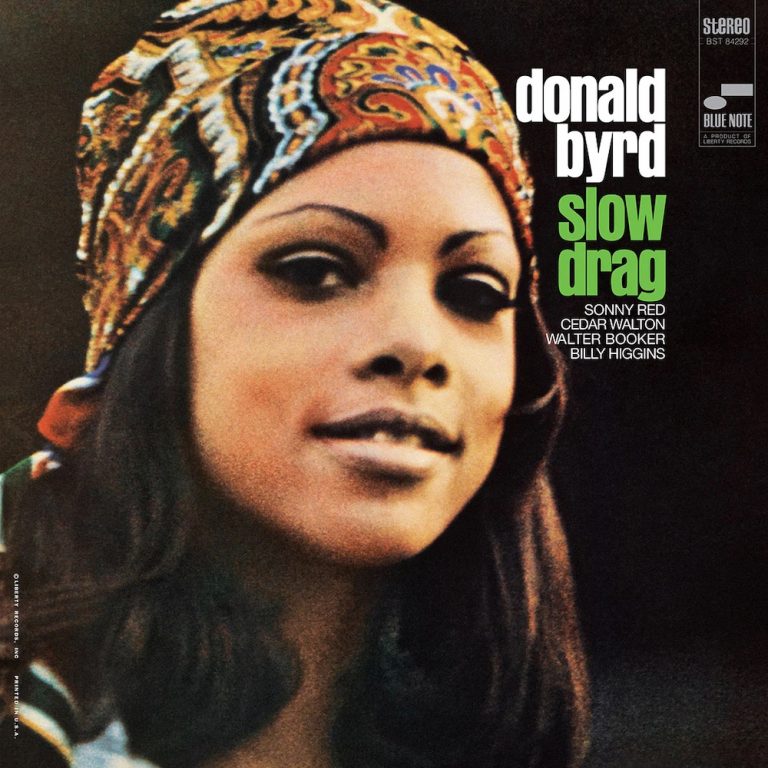

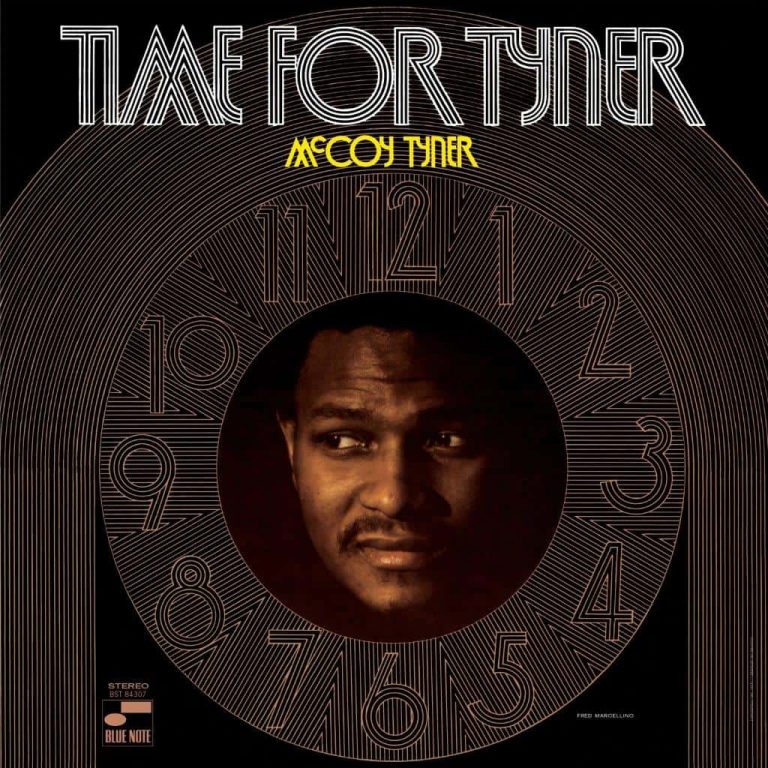

JH: Some people watch TV at night – I listen to records and have for years and years. So I’m pulling out titles and enjoying what I’m hearing, but I’m also working in the sense that I’m always making lists. I’ve got this gigantic list of titles. There’s records I pull out that are good, but there’s not necessarily a need for them to come out. But then there’s a lot where I listen and think, “Imagine what this could sound like!“ We’re also working way in advance. So the records that just came out, Donald Byrd’s “Slow Drag“ and McCoy Tyner’s “Time for Tyner“, were mastered two years ago. Because of the lead time and getting in the queue at the pressing plant. That’s just the world of vinyl at the moment.

DONALD BYRD Slow Drag

Available to purchase from our US store.

MCCOY TYNER Time For Tyner

Available to purchase from our US store.EJ: I assume that you don’t put out records you don’t like, but do you have a personal favourite from the Tone Poet catalogue?

JH: Each one has meaning to me, or I wouldn’t have picked it. I really love all of them, it depends on my mood. But yeah, I’ll bring it up just because it’s the last thing I listened to. It is not out yet, but there’s a McCoy Tyner coming later this year, called “Extensions“, that I was playing last night. And I realised this was probably the 20th time I played this test pressing. So it was dawning on me – I pulled this one out just for the pure joy of it! It’s coming out in autumn. It’s got Alice Coltrane, Wayne Shorter, Gary Bartz, Ron Carter and Elvin Jones on it. Just purely as a fan, I can’t get enough of that. Is that the favourite of all of them? I don’t know. But it’s certainly one of them.

Darrel Sheinman’s four Tone Poet catalogue favourites

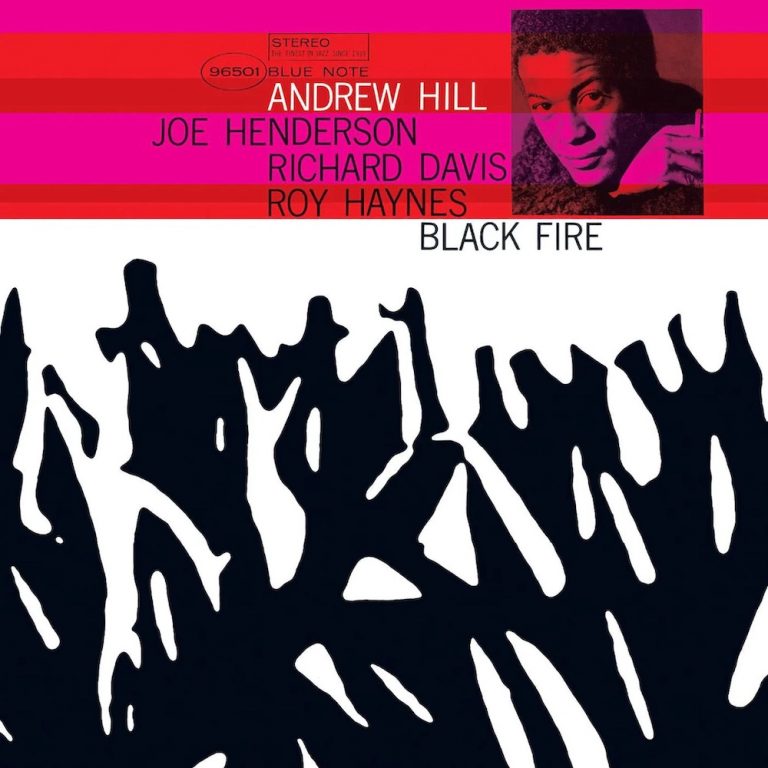

ANDREW HILL Black Fire

Available to purchase from our US store.JH: Isn’t it amazing that there were these players that Alfred Lion really loved but that were not commercially a big deal at the time? People forget that when he signed Monk in ’47, those records didn’t sell. People thought it was weird, they just weren’t quite ready to process his genius just yet. The musicians knew, but people had to kind of catch up. And Alfred hung in there. He did the same with Andrew Hill. You wonder, these days, would that still be the case? Would you have someone being that patient to hang in there because he knows it’s good?

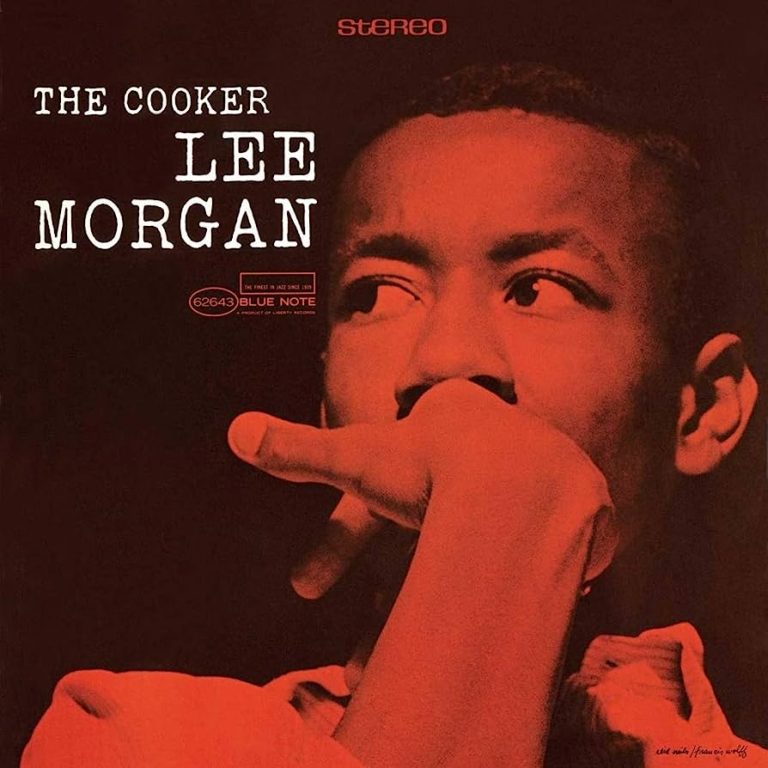

LEE MORGAN The Cooker

Available to purchase from our US store.JH: My man “Philly“ Joe Jones on there. Excellent. That “Night In Tunisia“ is a thrill ride every time. Rudy is having a great day in the studio in Hackensack. Good choice.

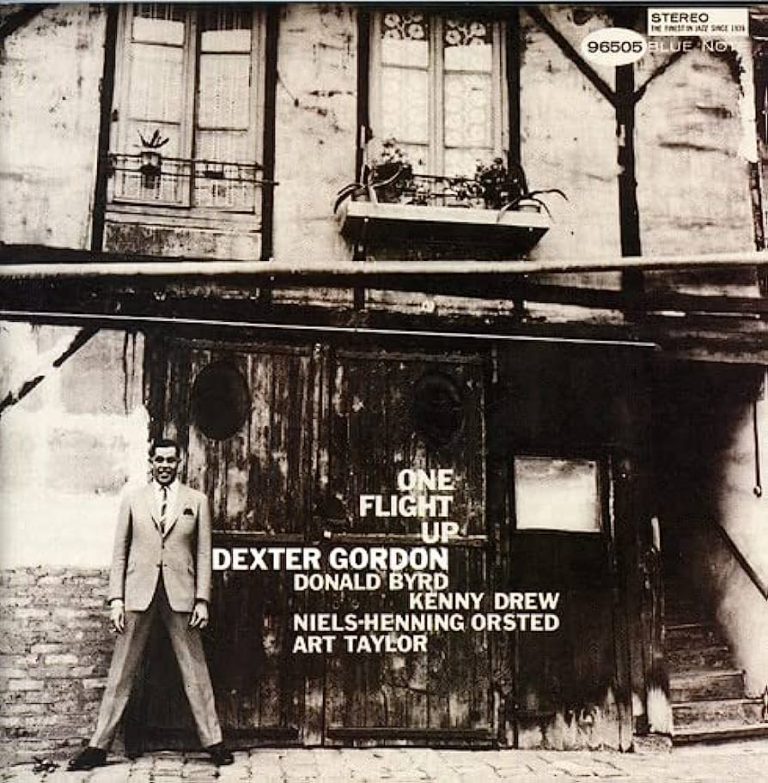

DEXTER GORDON One Flight Up

Available to purchase from our US store.JH: That one to me was a very risky one in some ways. It wasn’t recorded by Rudy van Gelder. This was done in Paris, I believe. But I mean, anybody who doesn’t like “Tanya“, that side-long track on Side A… I mean, if you don’t like that, I can’t help you.

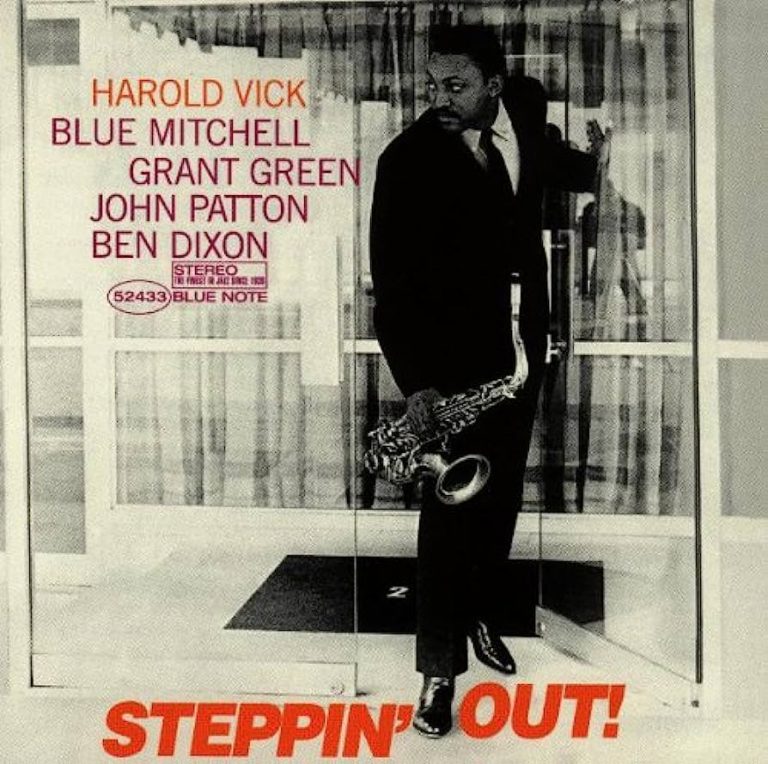

HAROLD VICK Steppin' Out!

Available to purchase from our US store.JH: That’s an interesting one. When you play the original, it sounds great and all, but there’s a problem in my opinion. There’s no bass player, so the bass is the Hammond B-3 played by Big John Patton. But the bass pedals aren’t heard, or you hear them, but there’s no real impact to it. So we put that up. And I played my original to death, but this thing grooves in an entirely different way. Hearing the master, there’s the bass pedals, they’re up there and present. And this is what they heard in the studio. This is what they were reacting to! Again, Rudy was doing what he had to do to keep those records playable and sold.

Stephan Kunze is a Berlin-based culture journalist who has been writing about music for magazines and newspapers since 2001. He’s a former Senior Music Editor and Global Editorial Lead at Spotify.

Header image: A box containing the original master tape of 1960 album, Lee Way, by jazz trumpeter Lee Morgan. Photo: ZUMA Press/Alamy.