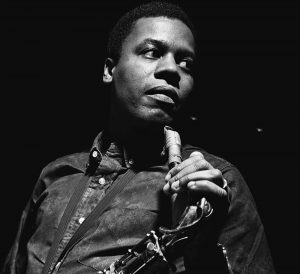

In 1964, aged 30, Wayne Shorter was riding high. Between 1959 and 1963, he’d been tenor saxophonist in the quintessential hard bop unit, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, quickly emerging as the group’s principal composer and musical director. At the same time, he’d cut three albums as a leader for the Chicago-based Vee-Jay Records, very much in the hard bop idiom but already showing signs of a nascent restlessness, a desire to stretch out and find new shapes.

But on April 29th that year, his rise assumed a new, more urgent trajectory as he entered the hallowed Van Gelder Studios in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, to cut his first session for Blue Note Records, released towards the end of the year as the album “Night Dreamer.”

WAYNE SHORTER Night Dreamer

Available to purchase from our US store.The quintet he assembled for the date was the toughest of the tough, featuring two former Messengers bandmates – trumpeter Lee Morgan and bassist Reggie Workman, who had been a mainstay of John Coltrane’s group until 1961 – plus pianist McCoy Tyner and drummer Elvin Jones, both then bringing startling new energies to light as half of Coltrane’s Classic Quartet.

There was no doubt he meant business. Indeed, the six pieces he recorded that day – five originals and one imaginative new arrangement – showed a clear development in his compositional genius. While clearly coming out of hard bop, with an irrepressible urge to swing still intact, there was also a new sense of economy, a sparer approach revealing a voice both visceral and cerebral, equal parts heart and mind.

It’s artfully apparent in the opening title track. Beginning with a romantic flourish from Tyner, the theme skips into a light-footed waltz in 3 ⁄ 4 time with a dreamy, carefree feel. Yet, from the very first note of Shorter’s solo, there’s a gritty authority, incisive and biting. “Oriental Folk Song” is based on a tune Shorter purportedly first heard in a commercial, later discovering it to be a traditional Chinese song. It’s introduced with a slow, meditative unfurling, before digging into an assured slow blues with Jones summoning great crashing waves at the drums.

WAYNE SHORTER Speak No Evil

Available to purchase from our US store.

After the sleepy ballad “Virgo” – featuring some gorgeously tender accompaniment from Tyner – the quintet dives into “Black Nile,” a heavy-swinging hard bop belter with Shorter’s solo earthy yet ethereal, Morgan in his element spitting out tight-lipped challenges, Tyner fleet and tuneful, and Jones taking a brief but thunderous solo. The final two tracks, “Charcoal Blues” and “Armageddon,” are muscular, mid tempo blues (with Jones clearly relishing the deep, straight-ahead setting his boss, Coltrane, was then in the process of leaving behind), yet both imbued with the same wistful search that would characterise Shorter’s work on later Blue Note classics such as “Speak No Evil.”

Night Dreamer was, then, a transitional moment for Shorter – the first in an astonishing 11-album run for Blue Note that saw him moving through more open-ended and interrogative post-bop, and up into the foothills of fusion in the early 70s. As if that weren’t enough, just five months after the recording of Night Dreamer, Shorter joined Miles Davis’s band, consolidating the line-up of the trumpeter’s world-shaking Second Great Quartet. But that’s another story.

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

Header photo: Francis Wolff / Blue Note Records