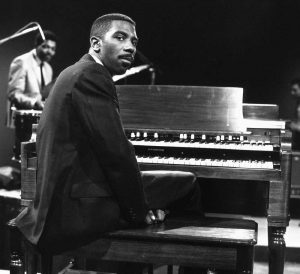

“The Hammond has body. It’s got depth – and resonance… It’s not so much that you can hear it. It’s the feeling that’s important…With the Hammond, you feel it in your bones,” Jimmy Smith told Downbeat magazine in a rare interview.

There have been many instances of musical instruments being repurposed in jazz. But none have been as revolutionary as Jimmy Smith’s innovations on the Hammond B-3 organ, which took it from being something of a novelty to one of the hippest and most progressive instruments in jazz.

Designed by an engineer Laurens Hammond in 1934, the Hammond organ (Model A) was conceived as a cheaper alternative to the pipe organ. It’s thought that a pastor by the name of Clarence Cobbs bought one of the earliest models for his congregation, the First Church of Deliverance in Chicago. It led to it becoming an important instrument in the development of gospel music.

Jazz musicians were quick to hear the potential of the Hammond organ; Count Basie played the Hammond A as early as 1939 with his Basie’s Bad Boys, and Fats Waller used the newly introduced Hammond B-3 on his 1950s albums for Riverside Records. But it was Wild Bill Davis who shook Jimmy Smith’s world when he first heard him playing the Hammond B-3 in the 1950s.

Self-taught on the piano, Smith dropped the instrument as soon as he heard the Hammond B-3. After buying his first model from a loan shark he retreated to a Philadelphia warehouse where he spent the next year perfecting his own unique style. “I pulled out that third harmonic and there! The bulb lit up, thunder and lightning! Stars came out of the sky,” he told All About Jazz in 1994. Blue Note’s Alfred Lion was at one of his early gigs and immediately signed him up for the label.

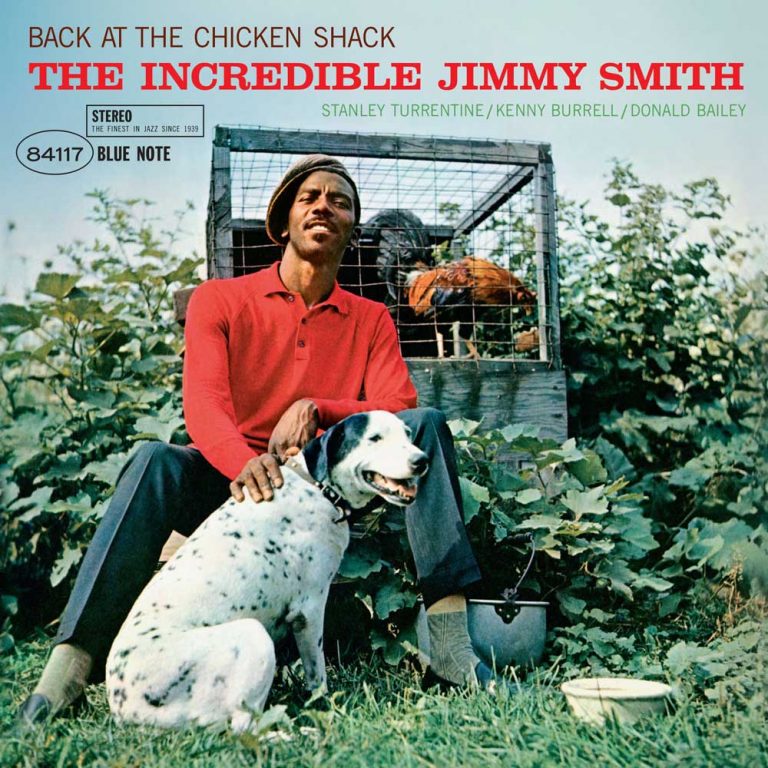

JIMMY SMITH Back At The Chicken Shack

Available to purchase from our US store.From 1957 to 1959 Jimmy Smith recorded an incredible 10 albums for Blue Note, each one breaking new ground for the Hammond B-3. On April 25 1960 he entered the Van Gelder Studio with tenorist Stanley Turrentine, guitarist Kenny Burrell and drummer Donald Bailey for what would turn out to be one of his most fruitful and famous sessions resulting in the albums “Midnight Special” and his best known “Back at the Chicken Shack”.

Jimmy Smith may have reinvented the Hammond B-3, but Blue Note had a deep roster of organists that crossed many different styles. Here are some highlights:

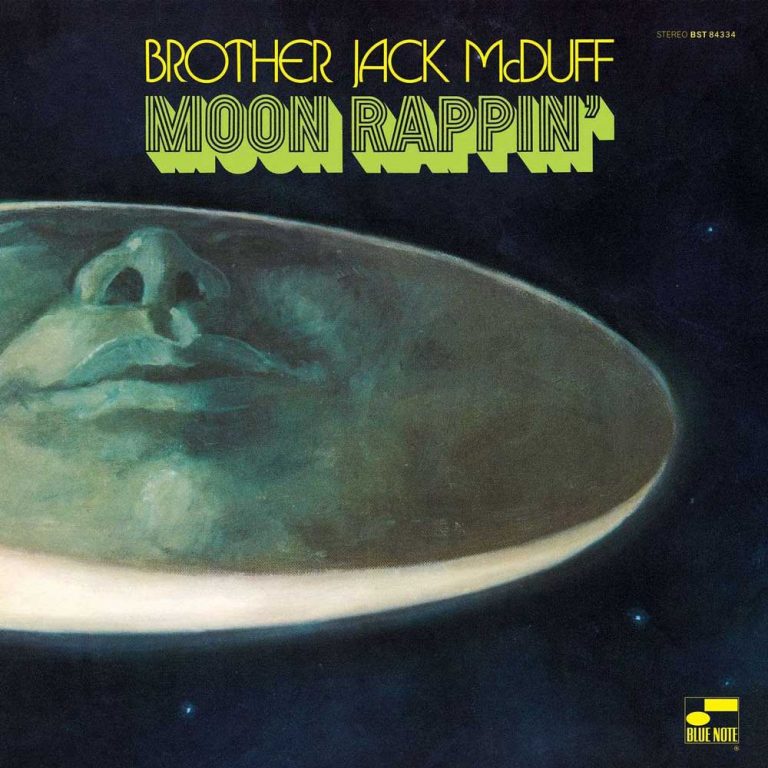

Next to Jimmy Smith the other jazz organist most associated with the Hammond B-3 is Brother Jack McDuff. On a series of albums for Prestige, Atlantic, and Cadet he became known as one of the leading soul jazz musicians of the era. His debut for Blue Note “Down Home Style” continued in this vein, but he took a left turn on this, his second of four albums for Blue Note between 1969-70. Spaced out funky and very much a record in tune with the times, “Moon Rappin” would reach new ears when A Tribe Called Quest sampled “Oblighetto” on both “Scenario” and “Check the Rhime”

BROTHER JACK McDUFF Moon Rappin'

Available to purchase from our US store.It was while playing in clubs with singer Lloyd Price that Kansas City-born Big John Patton started to experiment with the Hammond B-3 whenever there was one around. His relationship with Blue Note began as a sideman to Grant Green and Lou Donaldson before “Along Came John” the first of over 10 albums for the label. The Van Gelder Studios session with producer Alfred Lion was notable for the addition to his trio of Blue Note vibraphone master Bobby Hutcherson on top form on the modal soul jazzer “Latona”.

BIG JOHN PATTON Let 'Em Roll

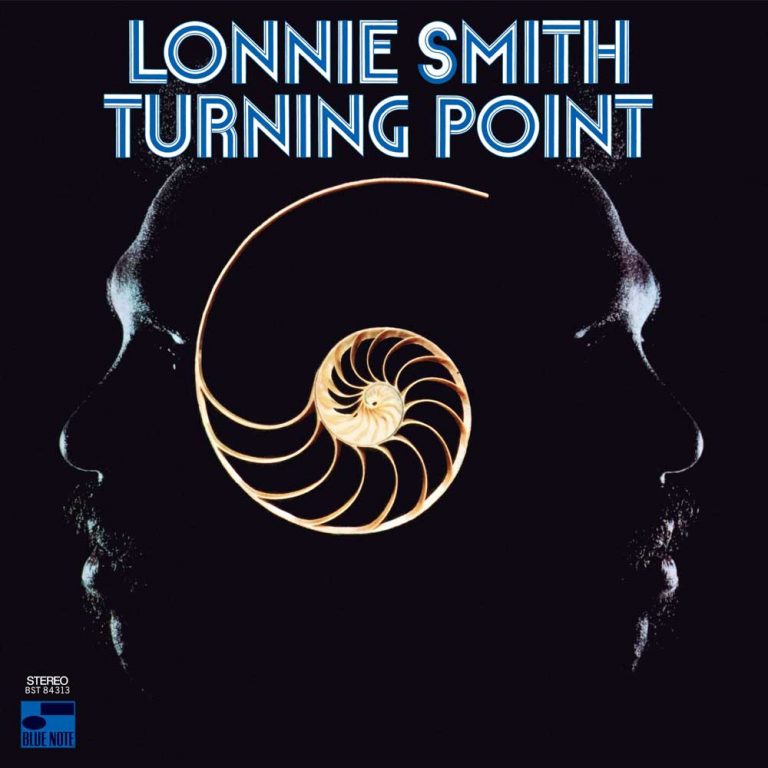

Available to purchase from our US store.“Dr.” Lonnie Smith’s first sessions for Blue Note were with Lou Donaldson replacing John Patton as organist on “Alligator Boogie”. His second album as leader for Blue Note “Turning Point” continued his association with trumpeter Lee Morgan, who was joined by two other horn players Bennie Maupin on tenor sax and Julian Priester on trombone. The rhythm section of guitarist Melvin Sparks and drummer Idris Muhammed (then known as Leo Morris) created a serious groove to possibly the funkiest of all the Hammond players own killer tracks like “See Saw” and the brooding “Slow High”.

Dr. LONNIE SMITH Turning Point

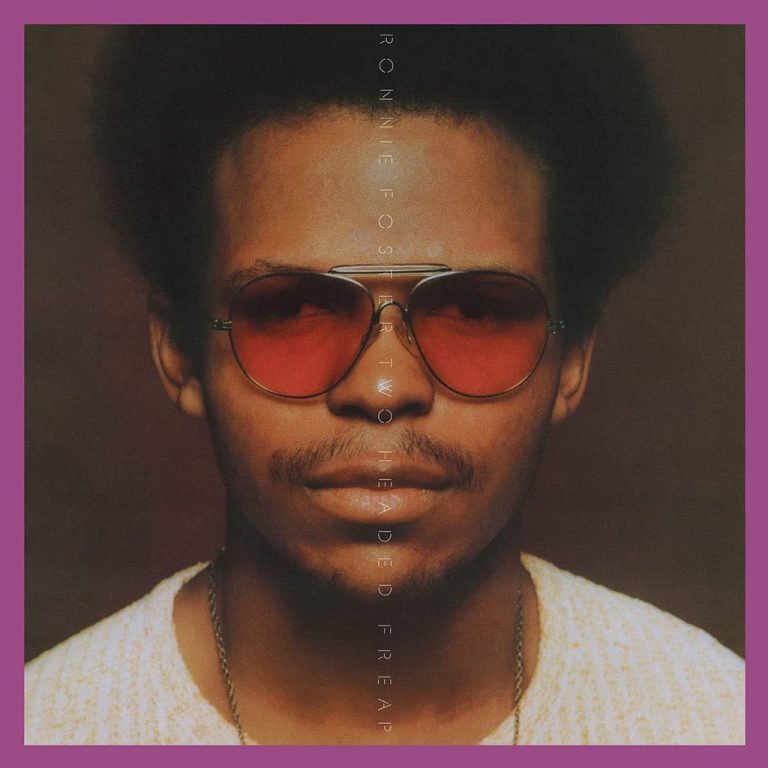

Available to purchase from our US store.He wasn’t the first Hammond player to be sampled in hip hop, but Ronnie Foster was perhaps the most famous, with his killer track “Mystic Brew’” creating the musical backbone of A Tribe Called Quest’s “Electric Relaxation” from their “Midnight Marauders” album. The original source album “Two-Headed Freap” was produced by George Butler whose stewardship of Blue Note into the jazz funk and fusion era was as daring as it was divisive. Right from the scorching opener “Chunky” it was one of Blue Note’s funkiest albums, with Foster playing the Hammond B-3 as raw as it ever would be.

RONNIE FOSTER Two Headed Freap

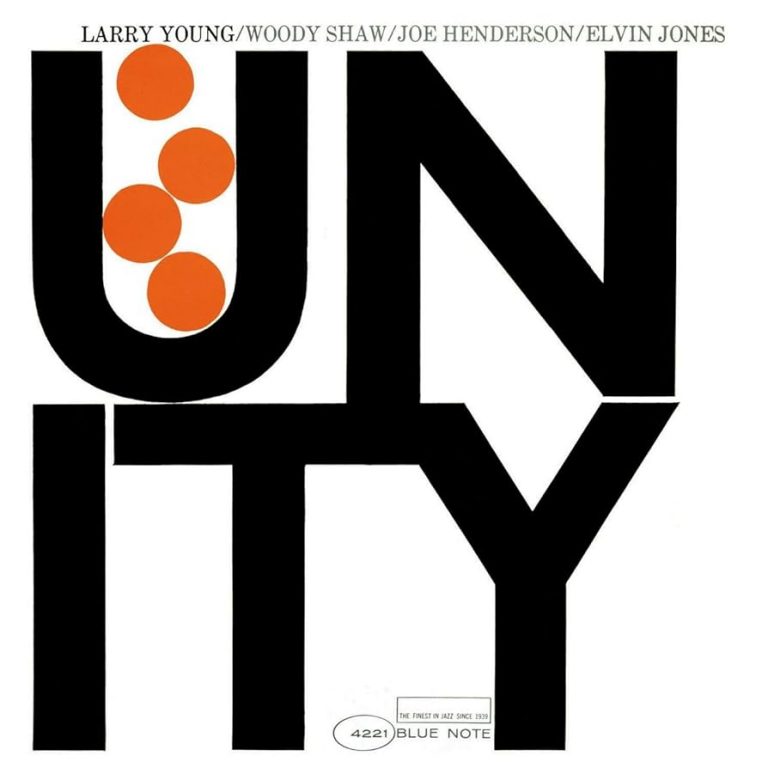

Available to purchase from our US store.The Hammond B3 went through many evolutions but perhaps its most radical shift since Jimmy Smith was the arrival of Larry Young. Where other Blue Note Hammond players of the sixties were firmly rooted in soul jazz, Young explored the instrument’s potential in a post bop modal setting. The New Jersey organist arrived at Blue Note with the 1965 album “Into Something” with guitarist Grant Green, drummer Elvin Jones and tenorist Sam Rivers. Its bop sensibilities were fully extended on the follow up again helmed by Elvin Jones but with fellow bop titans Joe Henderson on tenor and Woody Shaw on trumpet. Through the 1970s Young continued to push the possibilities of the jazz organ with the avant garde jazz funk album “Lawrence of Newark” and the funk drive fusion and future rare groove classic “Larry Young’s Fuel”.

LARRY YOUNG Unity

Available to purchase from our US store.Find all of these and more B-3 classics in the Everything Jazz Hammond B-3 Collection:

Read on…How George Butler took Blue Note Records sky high

Andy Thomas is a London based writer who has contributed regularly to Straight No Chaser, Wax Poetics, We Jazz, Red Bull Music Academy, and Bandcamp Daily. He has also written liner notes for Strut, Soul Jazz and Brownswood Recordings as well as storyboards for short films at RBMA.

Header image: Jimmy Smith. Photo: David Redfern/Redferns via Getty.