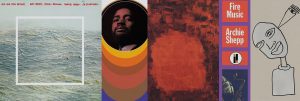

SHANNON J. EFFINGER: AHMAD JAMAL’s “THE AWAKENING” (VERVE BY REQUEST)

Ahmad Jamal was my last artist interview in February 2020, roughly five weeks before the pandemic lockdown would upend nearly all of our lives forever. While I met him some years ago, during a failed photo op at the Atlanta Jazz Festival (long story), this was the first – and last – conversation I would have with him.

It was just a few days before his Kennedy Center engagement. He was warm, gracious, and open, yet it was still hard for me not to be nervous while talking with him. I was sitting down with a living giant. Jamal is far more than a veritable icon. Like his contemporaries – notably, Randy Weston and Horace Silver – Jamal has a prowess for making the complex simple, embracing “less is more” with both hands, allowing every space to be just as crucial as the notes of a tune.

While “Poinciana” was my point of entry into his vast oeuvre, “The Awakening” was one of the first albums that solidified Jamal’s greatness. As with other releases – Miles Davis’s “Bitches Brew”, Jackie McLean’s “Demon Dance”, Lee Morgan’s “Live at the Lighthouse” — Jamal’s “Awakening” ushers in a new wave of progressive jazz, music that compels more from its artists and directly reflects both the times and themselves as artists.

Interestingly enough, Jamal and I had a lengthy conversation (not for publication) about how artists have sampled his work over the years, and his vast influence on hip-hop alone is evident. “I Love Music” is a masterful example of deep introspection. It opens with a motif of repetitive loops that gradually swell in timbre and rhythmic timing, bringing us on his quest for spirituality, at least for the first four minutes. Then, he resolves into a cool place, taking things down with sparse notes yet still melodic. Many listeners are perhaps most familiar with the melody, as producer Pete Rock lifts a few bars to create “The World is Yours” from Nas’s classic 1994 debut release, “Illmatic”.

Paying homage to Herbie Hancock with a reworking of “Dolphin Dance,” drawing inspiration from the “Maiden Voyage” version, Hancock’s approach to timing and precision feels intentional, giving the group – Freddie Hubbard, Ron Carter, Tony Williams, and George Coleman – ample room to stretch. With Jamal’s version, he shifts Hancock’s familiar opening refrain with a melodic turn that could have easily been a short cadenza. Another exemplary moment of exploration, his take on “Dolphin Dance” best showcases his trio – Jamil Nasser on bass and drummer Frank Gant. It soon segues into Hancock’s version but with Jamal’s punctuated chord progressions and nuanced flourishes. Around 2:44, Jamal deviates into yet another familiar passage, sampled by producer No I.D. for “Resurrection,” on the eponymous second album from rapper Common.

Jamal’s passing earlier this spring is still hard to accept. He was an idol for me, with my burgeoning musical ear, and remains one for me today.

AHMAD JAMAL The Awakening LP - Verve By Request Series

Available to purchase from our US store.Shannon J. Effinger (Shannon Ali) is a New York City-based arts journalist. Her writing on all things music regularly appears in The New York Times, Washington Post, Pitchfork, Downbeat, and NPR.

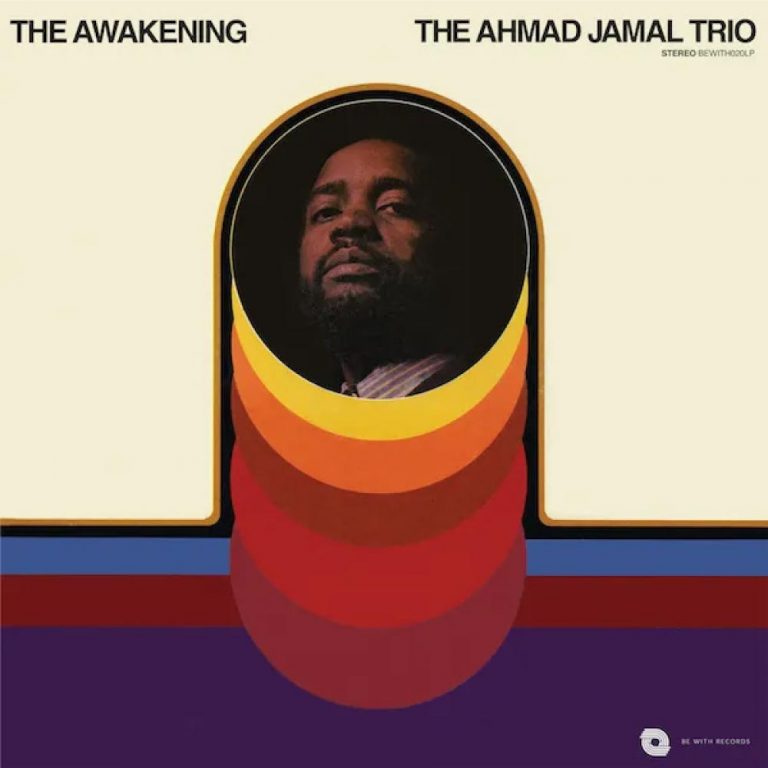

Stephan Kunze: Meshell Ndegeocello’s “The Omnichord Real Book” (Blue Note)

I loved playing this album really loud in the summer, opening the doors and windows wide to let the fresh air in. It truly made me feel like the pandemic era was finally over, but the music also reminded me that the struggle never ends.

Is this a jazz album? If you ask Meshell Ndegeocello, she’ll probably say no. At least she did when I asked her over Zoom one evening in early 2023. She cited musician Nicholas Payton, who in his provocative 2011 article “Why Jazz Isn’t Cool Anymore“ wrote: “Jazz is a brand. Jazz ain’t music, it’s marketing, and bad marketing at that.“ Meshell agrees with that notion: “Jazz has morphed. It’s a generalisation to sell something, and I can’t buy into that.“ Just like Payton preferred the term “Postmodern New Orleans music“, she would like people to see her songs as “Black American music“.

“The Omnichord Real Book” might still be classified as jazz, mostly because it was her first album for Blue Note and it featured some amazing players that are usually grouped into the genre – like Jason Moran, Ambrose Akinmusire, or Jeff Parker. But first and foremost, it’s a fresh and unclassifiable body of work, a full-on fusion of electric jazz, cosmic funk, fierce Afrobeat and futuristic hip-hop that evokes the spirits of Prince, Fela Kuti, Alice Coltrane, Miles Davis, Sun Ra, Lee Perry, and J Dilla.

Ndegeocello performs the magic trick of making this sound timeless and contemporary at the same time. Some of this music sounds not extremely far off from the progressive L.A. beat scene of the 2010s, like a Thundercat album produced by Sa-Ra maybe. Her last couple of albums were quiet, almost introverted affairs in comparison, born out of her love of classic, acoustic song craft. This one sounds more like a 72-minute block party on the mothership.

The song I played the most was “Virgo“: Eight and a half minutes of spiritual jazz grooves, with Brandee Younger on harp and Julius Rodriguez on a Farfisa organ. It’s such a jam!

MESHELL NDEGEOCELLO The Omnichord Real Book

Available to purchase from our US store.Stephan Kunze is a content editor for Everything Jazz. He’s a music writer, culture journalist and book author who has held leading positions at Spotify and Juice magazine. He lives in Berlin and in a tiny village in the rural Northeast of Germany.

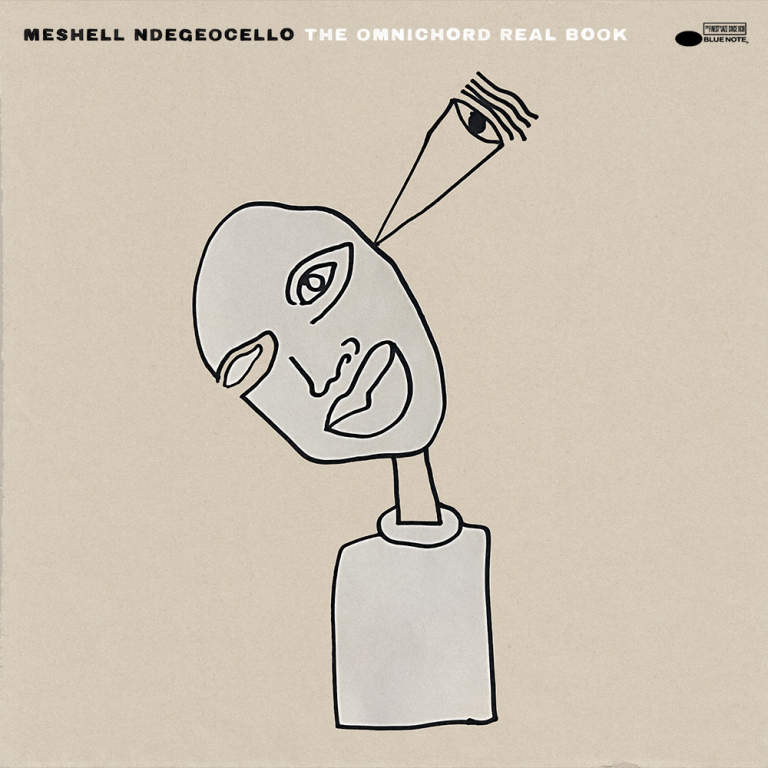

Max Cole: Don Cherry, Dewey Redman, Charlie Haden, Ed Blackwell’S “Old And New Dreams” (ECM Luminessence)

In many ways, this album sounds like it could have been recorded yesterday, rather than 44 years ago in Oslo’s Talent Studio, aka The Whale. The music occupies a certain timeless zone: it’s modern yet nostalgic, free yet lyrical, with a swinging, percussive pulse at its centre.

Old And New Dreams consisted of Don Cherry (trumpet), Dewey Redman (sax), Charlie Haden (bass) and Ed Blackwell (drums), four sidemen of Ornette Coleman who wished to celebrate and revisit some of Coleman’s musical ideas. Perhaps it’s this sense of looking back and forward at the same time gives the album its evergreen quality.

The way each side of their second album is sequenced is thus: the group plays a Coleman composition, and then splinters off in response over two other tracks, with each of the quartet supplying a composition. In this sense the Coleman tracks are a bit like palate cleansers – resetting the session before the group dives off into unmarked territories. But the Coleman association shouldn’t be overstated. The album doesn’t sound like “The Shape Of Jazz To Come”, but rather a reimagining of those initial blazing, pioneering sounds filtered through the folk music of Africa, Europe and India – a kind of global folk jazz that also incorporates plenty of earthy, bluesy feeling.

The version of “Lonely Woman” that opens the album is a superlative rendering, and the ballad’s anguish is more meandering and stretched-out than the original. It captures the feeling of a sad, lost soul exceptionally, and sets the bar for what follows. “Togo” is an Ed Blackwell composition, with extended drum sections nodding towards the Ewe drummers of West Africa. “Guinea” sees the group teleport along the Atlantic coast, as Cherry jumps on the piano for a rare moment of chordal color.

On the B-side, “Open Or Close” was a previously unknown Coleman track that Cherry fished out of his collection of Coleman sketches dating back to the 1950s. It’s a pacey bop that unfolds freely along solo sections, in between the loose, stop-start figures at the top and the close. The arrangement is typical of free jazz at the time, an almost archetypal slice of Coleman’s style of jazz. It’s kind of amazing to think that it’s the Coleman tracks that are the familiar signposts on the Old And New Dreams map, but that’s how it feels when Redman’s “Orbit of La-Ba” beams in next, opening with flurries of his double-reeded zurna. It evokes a place that’s neither China or India, but instead somewhere deep in the imagination, while Blackwell and Haden conjure up an ominous tribal rhythm. The album closes with “Song For The Whales,” a reverb-drenched excursion on bass that sees Haden attempt to convene with the ocean, in a haunting composition that is ecologically-minded and full of feeling.

I loved listening to this record again this year. It’s a fine balance between anchored and free, but you can hear the musicians searching for ways out of the loops they might have found themselves caught in. And this year, when the world seems doomed to repeat mistakes, and bad news is on replay, this album brings me hope that we might have the courage to try something new, while at the same time honoring past achievements.

DON CHERRY, DEWEY REDMAN, CHARLIE HADEN, ED BLACKWELL Old And New Dreams

Available to purchase from our US store.Max Cole is a Düsseldorf-based writer and music enthusiast who has written for record labels and magazines such as Straight No Chaser, Kindred Spirits, Rush Hour, South of North, International Feel and the Red Bull Music Academy.

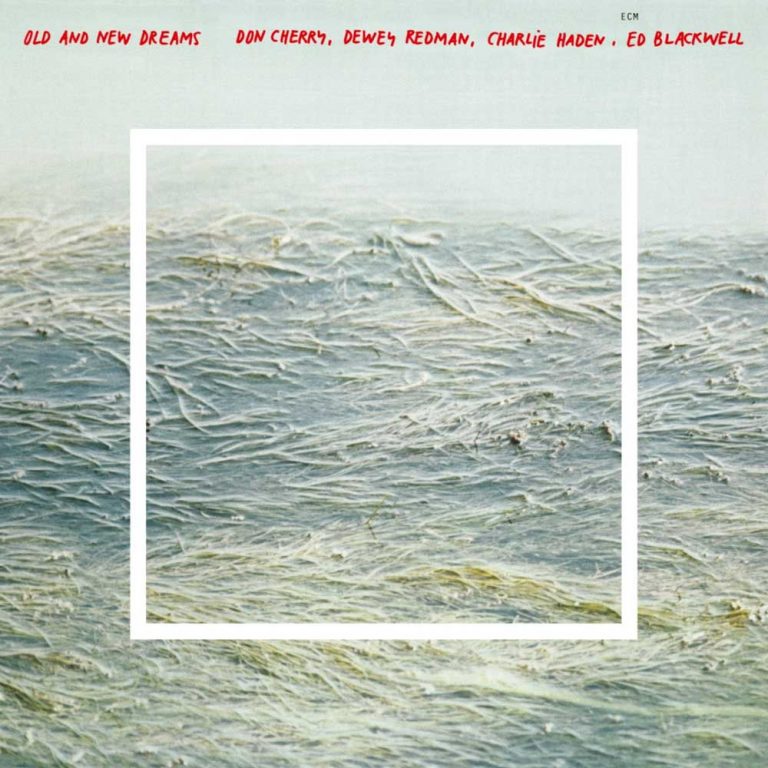

ANDY THOMAS: Archie Shepp’s “Fire Music” (Impulse!)

Riots in Watts that left 34 people dead, the assassination of Malcolm X, the Selma Freedom March to Montgomery, Alabama. 1965 was a momentous year for the Civil Rights and Black Power movement. It was also the year saxophonist Archie Shepp released “Fire Music”, his second album for Impulse! and next to the 1972 outing for the label, “Attica Blues”, his best known.

Amongst the most revolutionary records released by Impulse!, it would thrust Archie Shepp into the vanguard of the New Thing of the mid-1960s with music that continues to reverberate loudly today as the album gets a welcome pressing on 180-gram vinyl.

Recorded the year after the Bob Thiele/Coltrane produced “Four For Trane” from 1964 and his appearance on Trane’s LP “Ascension” the following year, “Fire Music” was the start of Shepp’s reputation as a radical free jazz firebrand allied with black nationalism.

The truth is he was also a multifaceted musician who would move effortlessly between free jazz, blues, and gospel. Equally he would often bridge the gap between challenging and accessible as heard on this perfect entry point to the music of Shepp.

The album was recorded at Van Gelder Studio on February 16 and March 9, 1965, with Shepp wielding his Selmer Saxophone like a sword alongside Marion Brown on alto saxophone, Reggie Johnson on bass, Joe Chambers on drums, Joseph Orange on trombone and Ted Curson on trumpet.

The cornerstone of “Fire Music” is “Malcolm, Malcolm Semper Malcolm”, Shepp’s dedication to Malcolm X who had been killed in February of that year. It opens with a haunting poem recited by Shepp, who often used spoken word within his jazz recordings. Over the next five minutes it builds into a sparse free jazz requiem, with Shepp’s horn veering between anger and beauty. It segues into “Prelude to a Kiss”, another example of how this most fiery musician could play with such warmth and elegance. Then there’s “Hambone”, the album’s most illustrative track in terms of Shepp’s trajectory between the blues and avant-garde.

The term Fire Music would become forever associated with the avant-garde playing that Shepp became known for, most recently used as the title for Tom Surgal’s 2021 documentary on free jazz. Once you’ve been here there is no turning back. Nor was there for Shepp. In the summer of 1969 he moved to Paris becoming one of the main American players in the avant-garde movement there recording a series of albums for BYG/Actuel. On his return to American he continued his conversations between free jazz, gospel and blues including the monumental “Attica Blues”.

A pivotal album that Shepp later recalled ostracised him from many in the jazz establishment at the time, “Fire Music” deserves to be up there with any of the New Thing recordings of the era.

ARCHIE SHEPP Fire Music

Available to purchase from our US store.Andy Thomas is a London-based writer who has contributed regularly to Straight No Chaser, Wax Poetics, We Jazz, Red Bull Music Academy, and Bandcamp Daily. He has also written liner notes for Strut, Soul Jazz and Brownswood Recordings.