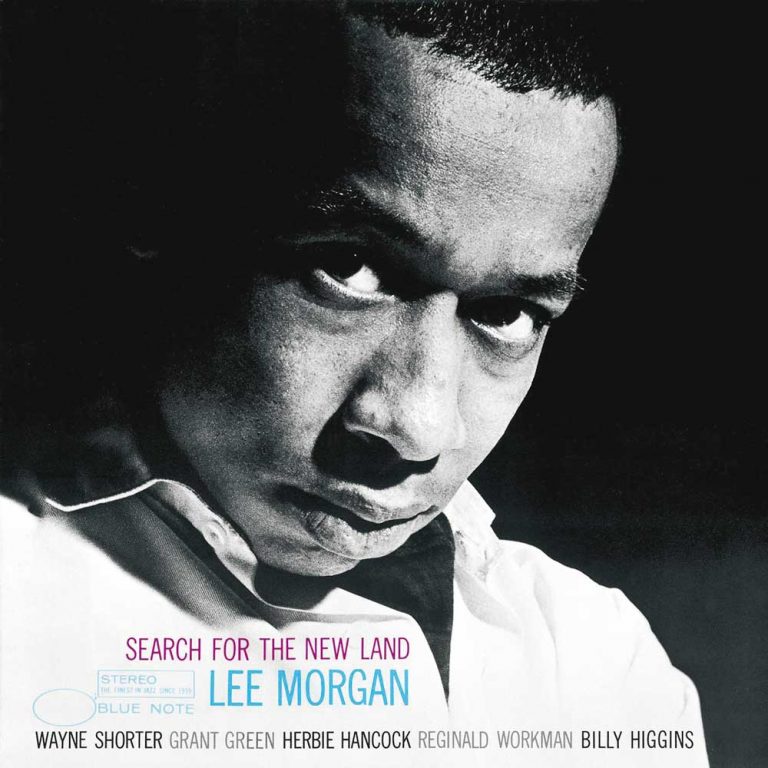

Just one look at the cover of Lee Morgan’s “Search For The New Land” tells you it’s serious. A black and white photo of Morgan in close up, head bowed and glancing up at the camera, cherubic and somehow vulnerable. It feels a long way from the brash showmanship and ebullience that had characterised the trumpeter’s playing with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

And it seems a wholly different artist to the one who had scored a major hit with the peppy soul-jazz boogaloo title track of his 1964 album “The Sidewinder” (In fact, “Search For The New Land” was recorded just a couple of months after “The Sidewinder” in February 1964, but not released until 1966.) Then there’s the list of sidemen appearing on the record, Blue Note stalwarts all, and about as heavy a personnel as it would be possible to assemble: tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter, bassist Reggie Workman (both fellow Jazz Messengers alumni), pianist Herbie Hancock, guitarist Grant Green and drummer Billy Higgins.

LEE MORGAN Search for the New Land

Available to purchase from our US store.And how about that title? Certainly it can be seen as a reference to the Civil Rights movement and the struggle of African nations to overthrow colonialism and achieve independence. That’s made clear by the title of Morgan’s hard-hitting, staccato-urgent “Mr. Kenyatta,” which begins the album’s second side – an obvious tribute to Jomo Kenyatta who had become Kenya’s first post-colonial President in 1964.

But it’s also possible to see Morgan’s search as a personal quest. Though just 25 at the time of recording, he’d already been through a lot. A former teen prodigy and major hard-bop stylist, by 1964 he had emerged from a drug-related slump that had precipitated his exit from the Jazz Messengers in 1961. Morgan was searching for a new land, yes, and maybe a new sense of self too.

All that seriousness and intensity is embodied in the album’s mesmerising title track, which, at nearly 16 minutes long, takes up most of the first side. From its opening moments, it’s clear this is no boogaloo bounce or hard-bop burner. Cymbals shimmer, bass lets forth a low arco drone, piano and guitar glisten like motes in a sunbeam, setting a mirage-like background for the emergence of Morgan’s wistful melody for twin horns.

Theme stated twice, Workman cuts in with a driving riff, Higgins’ whip-crack snare dances around a tough waltz and Hancock slices off stabbing chords, before horns sketch out a second, sprightlier theme and the band dissolves back into the opening aubade. This cyclical structure of theme, vamp, dissolve, theme plays out over the next 10-plus-minutes, with Shorter, Morgan, Hancock and Green each taking an unhurried, masterful solo in the vamp section.

Morgan’s solo is a revelation. Coming in with a typically pristine and strident tone, he quickly seems to pull back from the high-energy, note-dense style with which he was usually associated, settling into a more sensitive consideration of tone and breath, overblowing one moment, issuing a hushed huff the next. The group interplay throughout Morgan’s solo is breath-taking: a few bars in, he slides into a rapid trill, eliciting a sudden, excited prance from Hancock and firework snare cracks from Higgins that sound and feel remarkably like the liberated free-jazz drum style of Sunny Murray.

In fact, in its own elegant way, “Search For The New Land” was every bit as radical as the abstract free-jazz then gathering pace in the mid-60s, negotiating a fresh and surprising relationship with hard bop that only a master of the form like Morgan could have contemplated. A new land, a new sound, a whole new way of being.

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

Header image: Gai Terrell/Redferns via Getty Images