Modern jazz was an umbrella term used to differentiate ‘50s jazz from ‘20s ‘trad’ or ‘classic’, but post-bop was also something of a one size fits all category. It essentially refers to music that consolidated bebop’s complex harmony and rhythms, and hard bop’s rousing gospel and Latin flavours, but also reflected the growing knowledge base and experimental thinking of the prime movers in jazz of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s.

The use of scales and modes, as well as European classical influences and unconventional tonality and meter, filtered into several of the landmark recordings of the era. While rooted in the soil of acoustic jazz, these new works had a different character to the albums made by bebop icons such as Charlie Parker. ‘Bird’s’ spirit was still in post-bop but it was now flying in several exciting new directions.

Branching Out: Four essential Post Bop albums

Quite simply one of the greatest jazz records of all time. “Somethin’ Else” is a calling card for modern music of any genre, for that matter. Alto saxophonist Adderley and trumpeter Miles Davis, scale heights of eloquent lyricism on the lengthy deconstructions of standards such as “Autumn Leaves” and “Love For Sale,” while a peerless rhythm section of pianist Hank Jones, drummer Art Blakey and double bassist Sam Jones is as supple as it is forceful. The simmering intensity of the music speaks of intelligence as well as passion.

Although he asserted himself as a highly gifted composer when a valued member of Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers, saxophonist Wayne Shorter created an incomparable body of work as a solo artist. His revered ‘60s Blue Note output had several seminal post-bop albums that continue to exert an enormous influence on contemporary players.

1964’s “Speak No Evil” is a chef d’oeuvre. Shorter’s ability to write themes that were vividly evocative and imagistic, such as the title track, are second to none. Backed by drummer Elvin Jones, double bassist Ron Carter, pianist Herbie Hancock, and trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, Shorter, also soloing brilliantly, hits a true creative peak.

Along with Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans made a vital contribution to the vocabulary of the piano trio during an eventful career.

Celebrated for the impressionistic subtleties he brought to Miles Davis’s “Kind Of Blue,” Evans was on outstanding form on “Trio ’64,” where the advanced interplay between himself, drummer Paul Motian and double bassist Gary Peacock, showed how improvised music could unfold like an easy flowing conversation, replete with as many digressions and asides as central themes.

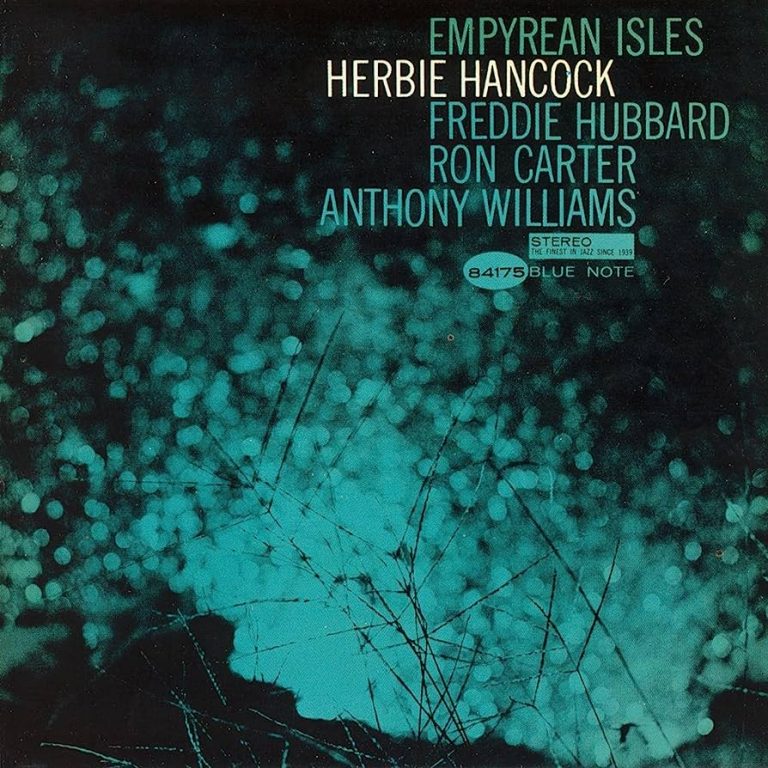

There are so many highlights from the first decade of Herbie Hancock’s career, let alone the five that followed, that it is hard to narrow down the embarrassment of riches. Yet “Empyrean Isles,” released in 1964, is something of a landmark in Hancock’s Blue Note tenure.

The stylistic breadth of the material, from the slinky Latin strut of ‘Cantaloupe Island’ to the enigmatic, abstract opus ‘The Egg’, reflects Hancock’s boundless ambition as well as his ability to be both entertaining and innovative. The band includes trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, double bassist Ron Carter and drum prodigy Tony Williams.

Read On…Miles Davis – Ascenseur pour l’échafaud: More Than a Movie Soundtrack

Kevin Le Gendre is a journalist and broadcaster with a special interest in black music. He contributes to Jazzwise, The Guardian and BBC Radio 3. His latest book is “Hear My Train A Comin’: The Songs Of JImi Hendrix”.

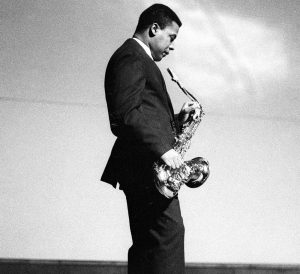

Header image: Wayne Shorter. Circa 1962. Photo: Michael Ochs Archives via Getty.