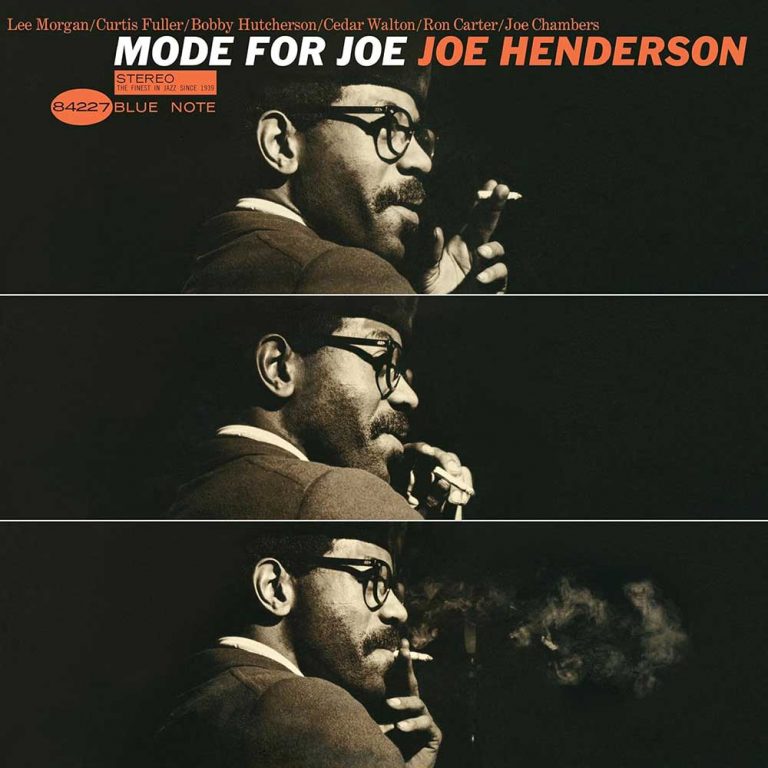

“The first time I heard a jazz record, it was “Mode for Joe” by saxophonist Joe Henderson,” Blue Note President Don Was told The Guardian newspaper in 2019. “He opened with these anguished cries, which really chimed with my own teenage angst, but then it slipped into this infectious swing. I never lost sight of that anguish, that need to keep it fresh and push the boundaries.”

Despite Joe Henderson’s fifth studio album for Blue Note making such a profound impact on the future head of Blue Note, when Don Was first heard Henderson, the tenorist had nowhere near the profile he has today. But over the years the albums he recorded for Blue Note during the exploratory mid ‘60s have achieved the same legendary status as those of peers like Wayne Shorter.

JOE HENDERSON Mode For Joe LP (Blue Note Classic Vinyl Series)

Available to purchase from our US store.Straddling hard bop, post bop, modal and the avant garde, Henderson is revered as one of Blue Note’s most multifaceted saxophonists. Guitarist John Scofield told DownBeat in 1992: “Joe Henderson is the essence of jazz. He embodies all the elements that came together in his generation: the virtuosity of hard bop and the avant-garde. He can be harmonically abstract and yet keep to the roots.”

When Henderson passed in June 2001, The Guardian’s John Fordham noted in his obituary that “Though he liked the middle register, which he occupied in a kind of penetrating murmur, he had a high-register sound as pure as a flute. He favoured fast, incisive statements of densely-packed runs, often ending in brusquely dissonant squalls or prolonged warbles, as if he were gargling with pebbles.”

The Ohio born Henderson earned his spurs in the Detroit jazz scene of the 1950s while studying at Wayne State University where his classmates included Yusef Lateef and Donald Byrd. After two years in the army, in 1962 he moved to New York. There he met Kenny Dorham who he recorded his first Blue Note session with, appearing on the trumpeter’s 1964 album “Una Mass”.

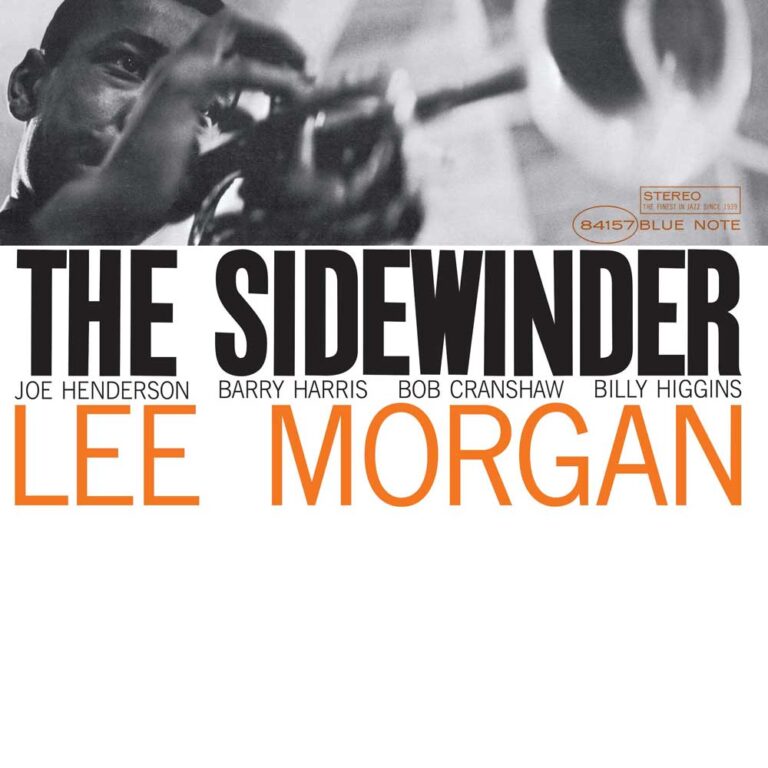

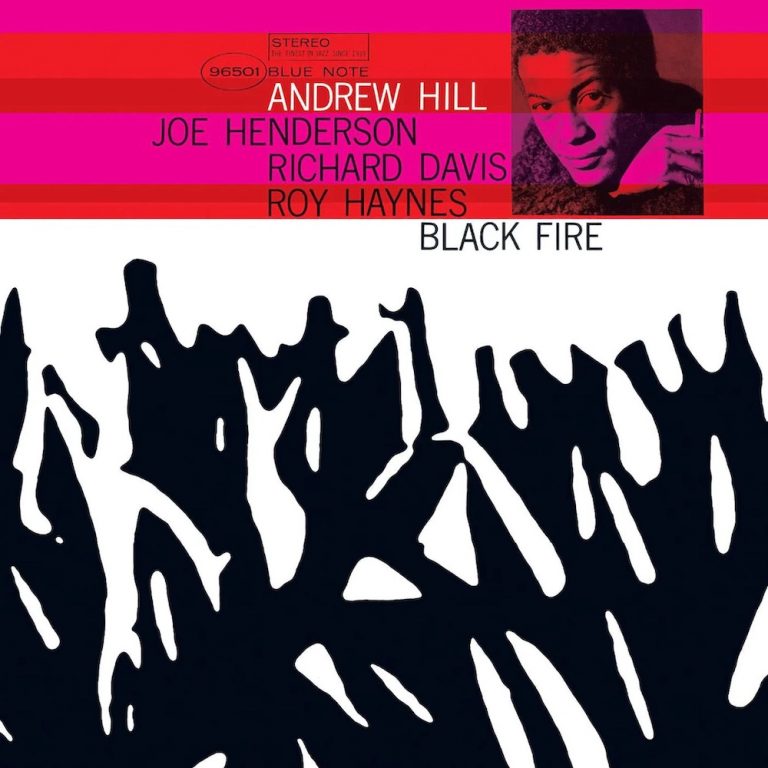

The session was recorded in 1963, a prolific year for Henderson that saw him play on such renowned albums as Lee Morgan’s “The Sidewinder” and Andrew Hill’s “Black Fire”.

LEE MORGAN The Sidewinder

Available to purchase from our US store.

ANDREW HILL Black Fire

Available to purchase from our US store.

In June of that year, two months after they had recorded “Una Mass”, Joe Henderson and Kenny Dorham went back to Van Gelder Studio with pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Butch Warren and drummer Pete La Roca. With two numbers written by Dorham and the rest by Henderson, “Page One” would go down as one of Blue Note’s great hard bop albums. Introduced by one of Francis Wolff’s greatest black and white cover portraits and with liner notes by Kenny Dorham, the album veered from the soaring dance classic “Blue Bossa” to the reflective ballad “La Mesha” and one of Henderson’s many future jazz standards “Recorda Me”.

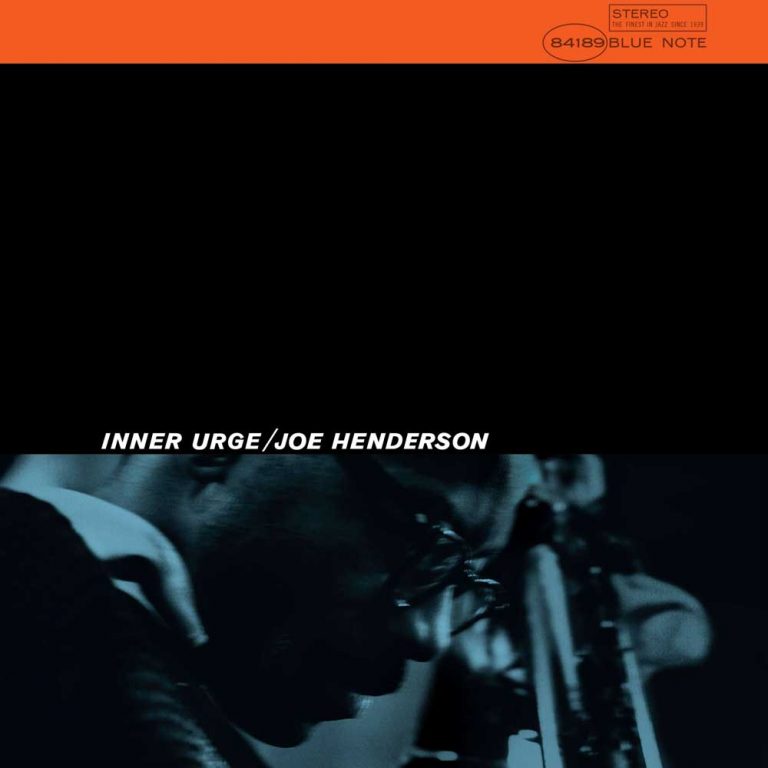

After two more quintet albums with Kenny Dorham, “Our Thing” and “In ’N Out”, Henderson stepped away from his regular partner for the first time for his most exploratory album to date. Recorded at Van Gelder Studio in November 30 1964 with John Coltrane Quartet’s McCoy Tyner and drummer Elvin Jones (alongside bassist Bob Cranshaw) a few days before they appeared on the legendary “A Love Supreme” session, Henderson’s own first quartet album thrust his horn out in the front of the mix.

JOE HENDERSON Inner Urge (Blue Note Classic Vinyl Series) LP

Available to purchase from our US store.As All About Jazz critic Norman Weinstein wrote in his review of the remastered “Inner Urge” in 2004, Henderson made “one of the major statements of jazz in the ’60s, recreating the political, economic, and social realities of the turbulent times more precisely than most recorded music of the ’60s.”

After the urgency of the title track came a blues dedicated to Thelonious Monk by the name of “Isotope”. As it fades out, the mournful cry of Henderson’s horn introduces the post bop modal masterpiece “El Barrio,” one of his most explorative compositions of the era and possibly his greatest ever solo. A mournful take on Duke Pearson’s ballad “You Know I Care” and a spirited version of Cole Porter’s “Night and Day” refer back to Henderson’s hard bop roots.

On January 27, 1966, two months before “Inner Urge” was released, Henderson recorded his first and only septet album for Blue Note. His final album of the sixties as a leader “Mode for Joe” featured a heavyweight line up of Lee Morgan on trumpet, Bobby Hutcherson on vibraphone, Curtis Fuller on trombone, Cedar Walton on piano, Ron Carter on bass, and Joe Chambers on drums. Written by Cedar Walton, fresh from recording with Art Blakey & The Messengers for the Blue Note album “Indestructible”, the title track was one Blue Note’s most famous modal numbers. While Henderson’s horn is upfront and strident throughout, you can hear the influence of the other members, from Lee Morgan’s soul jazz swagger on “Free Wheelin” to Bobby Hutcherson’s post bop harmonic invention on “Caribbean Fire Dance”. The latter features Henderson and Morgan duelling at their fiery best with a killer modal piano line by Cedar Walton pulsating underneath.

It was Henderson’s last Blue Note album as a leader although as a sideman he would appear on such notable sessions as Freddie Hubbard’s “Blue Spirits”, McCoy Tyner’s “The Real McCoy” and Herbie Hancock’s “The Prisoner”. But it was on the albums he recorded with Alice Coltrane like “Ptah, the El Daoud” for Impulse! from 1970 and “The Elements” from 1974 for Milestone that Henderson’s full creative force would be realised. A force that began at Blue Note in the mid sixties.

Read on… Jackie McLean – “Action”

Andy Thomas is a London based writer who has contributed regularly to Straight No Chaser, Wax Poetics, We Jazz, Red Bull Music Academy, and Bandcamp Daily. He has also written liner notes for Strut, Soul Jazz and Brownswood Recordings.

Header Image: Joe Henderson. Photo: Robert Abbott Sengstacke via Getty.