“I always had thought of free music, even when I was still small,” Ayler told Melody Maker in 1966. “I’d be playing a ballad and my father would say, ‘Get back to the melody. Stop playing that nonsense.’ But I knew there was something there. I’d be standing in a corner playing and trying to communicate with a spirit that I knew nothing about at that particular age.”

Ayler’s desire to speak with a spirit through “Ghosts” had become obvious by 1964, when he’d named his second solo album “Ghosts” and included two different variations of it. That same year, he and Don Cherry explored “Ghosts” two other ways on the album “Vibrations” – and then quoted its motif on album-closer “Mothers.” On “Spiritual Unity,” his 1964 album with the Albert Ayler Trio, the bandleader, then 28, again tackled the song two ways, one of which extended beyond ten minutes. In 1968, Ayler even set lyrics to “Ghosts,” which he delivered between nonverbal, marble-mouthed warbles.

Ayler told writer Nat Henthoff in 1966 that his desire with the “Ghosts” melody was to “play something… that people can hum.” It worked. So beguiling is the song that Cherry once suggested in liner notes that it “should be our national anthem.”

Ayler knew something about deliberate melodies. He got his start in gutbucket R&B and electric blues bands, and during summer breaks as a teenager he played in harmonica player Little Walter’s touring unit. After enlisting in the military at 22, Ayler served in the U.S. Army Regiment Band (notably, alongside experimental composer Harold Budd). You can hear military march ideas – the clarity of tone, the pacing of the melody – in “Ghosts.”

By the time he landed in New York in the mid-1960s, Ayler seemed so obsessed with the “Ghosts” motif that he seemed to be trying to blow a relentless earworm out of his head, one that repeated involuntarily and with a kind of malice. In other instances he embraced its essence, working through it from different emotive angles.

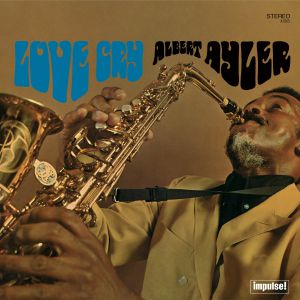

ALBERT AYLER Love Cry

Available to purchase from our US store.“The scream I was playing then was peace to me at that time,” Ayler told Melody Maker in 1966 when asked about the din he was making. “Whatever was inside of me, something was happening and I did not know exactly what it was. America was going through such a big change, and I’d been traveling all over, seen it all, and had to play it out of me. But now it’s peaceful. It’s more like a silent scream.”

The concentrated, dense “Love Cry” version may last less than three minutes, but the quartet of players make up for it in depth of expression. Blowing the motif as though awakening a platoon at sunrise, Ayler works with his younger brother Donald Ayler on trumpet, bassist Alan Silva and the 36-armed drumming of Milford Graves – who seems to spill the sticks onto his kit – to swirl around the melody. The band offers counterpoints to Albert’s call-and-response tenor bursts, which are blown with deep Coltrane-esque gusto. The Ayler brothers, taught by a jazz-loving father, never sounded better together on a studio recording than on “Love Cry.”

Tragically, “Love Cry” was the last time that the Ayler brothers collaborated on a studio recording. Albert, whose struggles with mental illness had grown increasingly acute, was found dead in New York’s East River in 1970, a few weeks after he disappeared, of a presumed suicide. Were it not such a magnetic work, his “Ghosts” earworm might have died with him. But it’s since become his signature piece.

For Ayler, that work, as with his entire oeuvre, was delivered on the wings of a medium that he considered the most powerful force in the universe. “I believe music can change people. When bop came, people acted differently than they had before,” he told one interviewer. “Our music should be able to remove frustration, to enable people to act more freely, to think more freely.”

Randall Roberts is an award-winning music and culture journalist, and a former music editor at the Los Angeles Times.

Header photo: Albert Ayler in a session for ABC/Impulse! Records ca. 1967-1968. Photo: PBH Images / Alamy.