Such was the intensity of Elvin Jones’ stint as drummer in John Coltrane’s groups – and so epochal the music they made together with bassist Jimmy Garrison and pianist McCoy Tyner as the Classic Quartet – that he will always be best remembered for that world-shaking tenure. Yet it’s easy to forget that the association lasted just six years.

Jones quit Coltrane’s employ in early 1966, shortly after Trane’s hiring of additional drummer Rashied Ali signalled a deepening of his commitment to exploring the wide-open possibilities of free jazz. By then, Jones had made enough of a name for himself to lead his own bands, both in the studio and onstage, where he enthusiastically pursued the heavy swinging, hard-bop modal aesthetic that had characterised his best work with Coltrane.

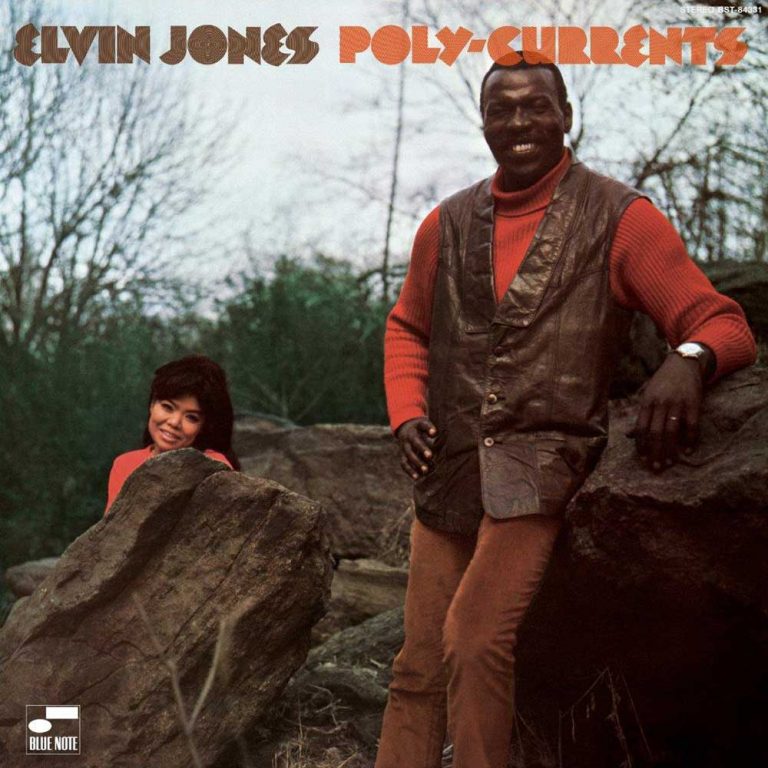

After the slightly underwhelming hotchpotch of 1967’s “Heavy Sounds” and 1968’s “Live at the Village Vanguard,” Jones hit his stride with two hard-hitting, stripped back trio albums – “Puttin’ It Together” and “The Ultimate,” both recorded in 1968 – featuring Garrison and young saxophonist/flautist Joe Farell. However, for his next album, “Poly-Currents” – recorded in 1969 and released on Blue Note the following year – Jones formed a more ambitious, expanded ensemble, which retained Farrell and added a whole lot more wind-power: Fred Tompkins on flute, Pepper Adams on baritone sax and, on tenor sax, the woefully under-appreciated tenor man, George Coleman, who had played in Miles Davis’ quintet, just prior to the arrival of Wayne Shorter. Rounding out the rhythm section was hard-bop bassist Wilbur Little and Cuban master percussionist Cándido Camero on congas.

It’s little surprise that this heavyweight crew cooks up some hefty jams, giving Jones plenty of opportunity to burn in a muscular, straight-ahead setting. Side one of the album is dominated by the nearly-14-minute Jones original, “Agenda.” Beginning with a classic Elvin Jones polyrhythmic drum riff – rim shots, toms and ride cymbal slotting together in hip complexity – it picks up a deep, modal bassline, before Farrell enters blowing an English horn (aka the oboe-like cors anglais).

Languorous and sinuous like a North African ney, it’s perfectly complemented by Adams’ buzzing baritone. With this unusual instrumentation setting a drowsy vibe, Jones takes a monumental solo – his longest on the album – full of thunderous triplets, firecracker snare rolls and booming kicks that amply demonstrate why he was known to nail his bass drum to the stage in performance.

Elsewhere, there are more meditative moods – particularly on two relatively brief, flute-led tracks, which give Jones the chance to demonstrate masterful brushwork: on Farrell’s delicate “Agappe Love” the lightest touch of brush on snare creates a gently sighing breeze, while on Tompkins’ “Yes” it’s all about the supple-wristed, syncopated snap of bristles on skin.

Two mid-tempo swingers complete the album: “Mr Jones” – credited to Jones’ wife, composer and classical pianist Keiko Jones – is a deep blues with congas adding a buoyant bounce and Coleman blowing hot; and Little’s “Whew” is built around a bass-led head with cheeky unison stabs, opening out into a 10-minute blowing session in which Jones works up some of the elemental energy that enlivened so many of Coltrane’s most timeless performances. As Jones swells, crashes and subsides like a tempestuous sea, there’s no doubting his reputation as one of the key architects of jazz drumming, and an ever-living avatar of the music.

Read On…Spring – Tony Williams’ Adventurous Early Masterpiece

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

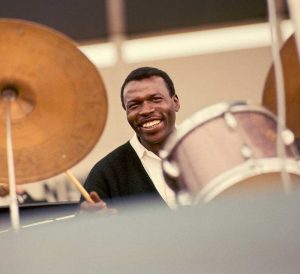

Header image: Elvin Jones. Photo: Gai Terrell/Redferns via Getty.