“Drummers don’t write – or at least, that’s what everybody believes,” percussionist Tony Williams (Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea) told Downbeat in a 1997 interview that noted his exasperation at the stereotype. “That’s other drummers. I’m a musician who plays drums. And I write.”

It is true, however, that fewer drummers than horn players have lead prominent jazz bands, and that, as lead melody creators, the wind-blowers have long trumped the rhythm makers when it comes to getting their names on album covers. One reason might be that it’s hard to connect with crowds when a drum kit is in the way. Plus: seated musicians cannot strut; drummers are too busy banging on things to engage with the crowd; and, to paraphrase Flava Flav, you can’t copyright a beat.

If drummers are different from others, maybe it’s because, as a whole, they’re busy listening for patterns – so have no time for your nonsense. They spy for ideas as they pass construction sites, as rain taps on rooftops or as crickets chirp.

Percussionist Brian Blade (Chick Corea, Wayne Shorter, Joshua Redman) describes one of his inspirations as “a groove that comes from the street culture. If you can play below sea level you’ve got it made.” He calls it “a certain feeling of the beat that finds its way in, whether it’s traditional jazz, R&B, or whatever.”

When drummers take the lead, the beat intensifies. Bandmates – even (gasp) tenor players – abide by the boss’s commands, which usually involves giving the percussion more room to move. Stuff gets more frantic and energetic. Need evidence? Here are five great drummer-led albums.

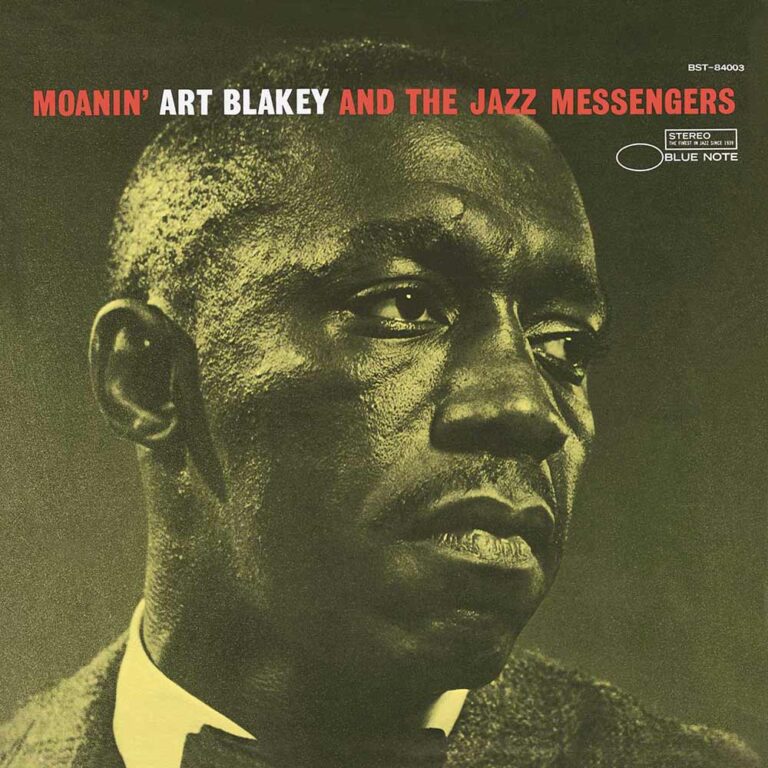

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers – “Moanin’”

ART BLAKEY AND THE JAZZ MESSENGERS Moanin'

Available to purchase from our US store.As the founder of the Jazz Messengers in the mid 1950s, archetypal hard-bop drummer Art Blakey helped define the sound of gritty, blues-driven jazz while serving as an early mentor to experts including Wayne Shorter, Lee Morgan and Freddie Hubbard. “Moanin’” is one of the great bop albums, a midnight burner that draws energy from trumpeter Morgan, tenor player Benny Golson, pianist Bobby Timmons and double bassist Jymie Merritt. The Timmons-penned title track, one of the most recognisable bop songs in the jazz canon, is a series of thrilling meditations on its central melody, a scene-setting work powered by a laid back, but somehow urgent, groove. The drama and expressiveness blossom from there as Blakey and band move through five other songs, most written by Golson.

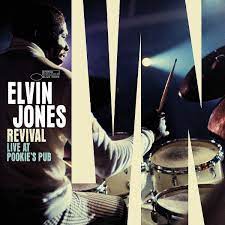

Elvin Jones – “Revival: Live at Pookie’s Pub”

ELVIN JONES Revival: Live at Pookie's Pub

Available to purchase from our US store.“This is my first group and I like being a leader, but then I guess I’ve been sort of a leader in most of the groups I’ve worked in. A drummer should conduct,” Elvin Jones told the writer Whitney Balliett in a brilliant 1968 profile for The New Yorker. At the time, the snare-snapping Jones was in the middle of an extended residency at Pookie’s Pub, a Manhattan dive near the Holland Tunnel with a capacity of 150. His former boss John Coltrane had died a few weeks before “Live at Pookie’s Pub” was recorded. Jones had left that band the year prior, after Coltrane added a second drummer, an arrangement that Jones couldn’t abide. (“There was too much going on, and it was ridiculous as far as I was concerned,” he said.)

That this album exists at all is due to the archeological work of expert producer Zev Feldman, who discovered the previously uncataloged tapes. Jones was then living in a ramshackle apartment not far away and barely scraping by in 1968, but at Pookie’s he conducted weekly live sessions alongside players including tenor saxophonist Joe Farrell, Billy Greene on (wonky, wobbly) piano and Wilbur Little on bass. Larry Young sits in to wrestle with the piano for a raucous take on “Gingerbread Boy.” That a microphone is perfectly placed to capture Jones’ work on the kit is a blessing.

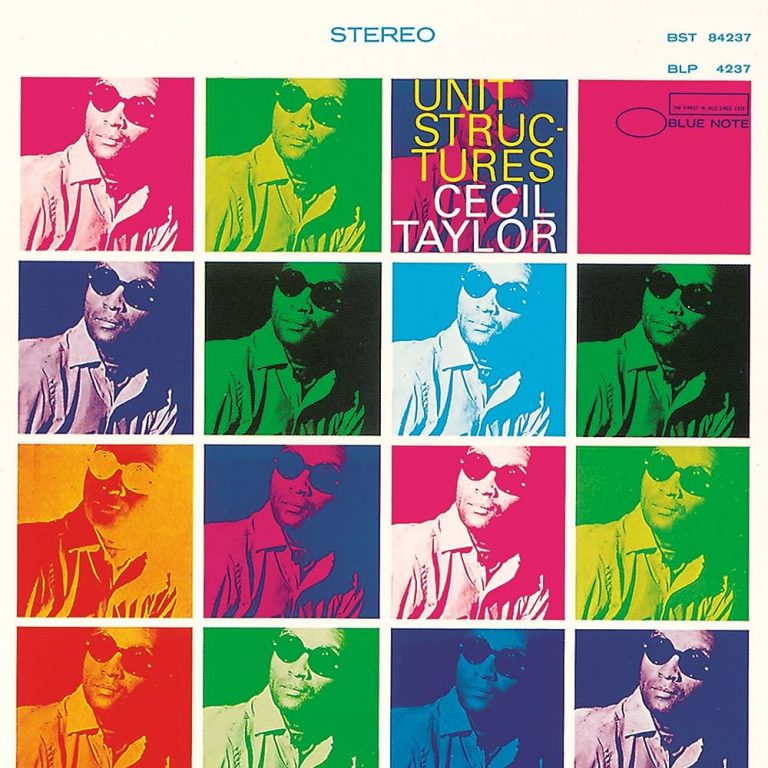

Cecil Taylor – “Unit Structures”

Cecil Taylor Unit Structures

Available to purchase from our US store.The piano is a percussion instrument driven by the sound of padded hammers striking tuned strings, and no musician better captures this truth than Cecil Taylor. An artist and musical theoretician famously described as playing piano as though its keys were 88 tuned drums, Taylor pounds, bangs and swipes at his instrument with the determination of a carpenter building a house. Released by Blue Note in 1966, Unit Structures is a percussion explosion where Taylor’s pointillistic piano runs seem to sprint alongside drummer Andrew Cyrille’s organised tom-and-kick drum entanglements. “Tales (8 Whisps)” begins as a two-way conversation between Taylor and Cyrille, one seamlessly joined partway through by double bassist Henry Grimes bowing a high, moaning note across a string.

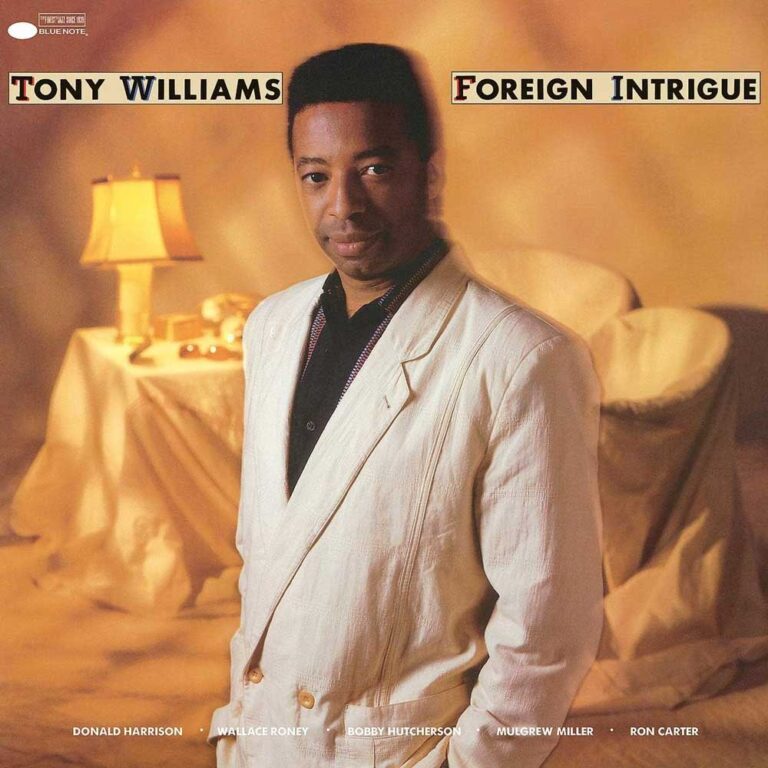

Tony Williams – “Foreign Intrigue”

TONY WILLIAMS Foreign Intrigue

Available to purchase from our US store.Don’t be fooled by the album cover, which suggests Tony Williams just lit a candle to seduce you with 1980s smoothness. This is some rad, expansive stuff from a key moment in the evolution of percussion. By the mid-1980s, forward-thinking drummers like Williams had started adding electronic beat-making instruments – triggers, pads and samplers – to their kits, resulting in synthetic pew-pew snares and weirdly toned tom-tom dots. Unlike his former boss Miles Davis in the mid-1980s, Williams doesn’t overdo it with the synth stuff, using it as one more weapon in his arsenal. “Clearways” showcases vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson and pianist Mulgrew Miller, and barely has any electronics. “Life of the Party,” on the other hand, jumps with electro-newness.

Makaya McCraven – Deciphering the Message

MAKAYA MCCRAVEN Deciphering the Message

Available to purchase from our US store.Chicago drummer and bandleader Makaya McCraven was given the keys to the Blue Note vault for Deciphering the Message, his 2021 record. Though often described as a remix album due to McCraven’s use of original recordings to make this, it’s more accurately called an augmented album. McCraven formed a band – vibraphonist Joel Ross, trumpeter Marquis Hill, guitarists Matt Gold and Jeff Parker, bassist Junius Paul, alto saxophonist Greg Ward and De’Sean Jones on tenor sax and flute – to added new instrumental layers and ideas to the records.

Read on…Roy Haynes Quartet – Out of the Afternoon

Randall Roberts is an award-winning music and culture journalist, and a former music editor at the Los Angeles Times.

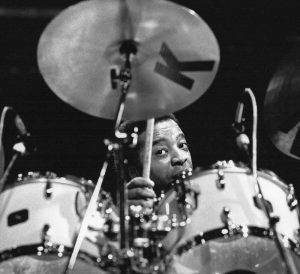

Header photo: Cary Hammond/Redferns via Getty