“I’m free. John did this. I got an offer to go to Japan but I won’t go 10,000 miles on someone else’s terms. I’ve been taking orders, in some form, all of my life; being a woman I’ve always been subservient — servant, nurse, cook. The man is number one. He must assume the position of leadership or where is he? In this country, the Black man is not leading. The only hope is through enough money to pay his way to privacy, freedom, independence…I’m glad I’m not a man. My true expression is in my art and my kids.”

Alice Coltrane quoted in Essence, December 1971

In December 1970, not long after recording “Journey in Satchidananda,” Alice Coltrane took a five-week trip to the Indian subcontinent. She swam in the Ganges, visited monasteries in the Himalayan Mountains, and made pilgrimages to holy sites including Rishikesh and the Taj Mahal. She spent several days at a spiritual retreat in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and attended the World Scientific Yoga Conference, a gathering of gurus, scholars, and students. The trip, she later wrote, brought an end to a cycle of suffering: “Having made the journey to the East, a most important part of my Sadhana (spiritual struggle) has been completed.”

And suffered, she had. It had been four years since the death of her husband, John, and two years since the death of her older half-brother, the bassist Ernie Farrow. She was 33 years old, taking care of four young children, and immersed in the sort of pain that one can only begin to make sense of as a necessary step in a spiritual journey.

There would be a lesson in the suffering, a purification of the spirit, she believed. She had taken practices of ascetic discipline to the limit, embarking on an extreme program of meditation, sometimes sitting for 20 hours a day. There were weeks when she only slept two hours. Her weight dropped to 95 pounds. She experienced hallucinations, heard sounds coming from trees and planets, and had to be hospitalized more than once, including once for self-inflicted burns. “There were demands made, definite demands, that took me away from the world, and at one point almost away from music, family, and all, because the sacrifice had to be within an inch of my life, almost literally,” she said in a 1970 interview. “I found that whatever questions that I might have had in my mind concerning whatever events in the future or past were answered. I think that it gave me freedom, that it gave me my true independence. The world cannot claim me anymore.”

By the time Alice took the stage at Carnegie Hall in early 1971, the spiritual purpose in her work had been made even clearer, galvanised by her travels. “The trip to the East gave me the spiritual motivation to come out more – to do more with my music,” she told Essence. “I also listened to a lot of beautiful sitar and vina [veena] music…and I’m going to use some of the chants I heard…some of the essence of the East.”

ALICE COLTRANE The Carnegie Hall Concert

Available to purchase from our US store.The Carnegie performance was one of several concerts and recordings in which she paid tribute to Swami Satchidananda, who had become her spiritual leader and had guided her on her trip to India and Ceylon. Other tributes to her newly found guru included “Journey in Satchidananda,” an album released just one week prior to the Carnegie performance, and “Universal Consciousness,” which she would begin recording a few months later and release later that year, the interior gatefold featuring a photo of the two of them together by the Ganges River. Alice even became a generous benefactor to the Integral Yoga Institute; in 1970, when the institute had outgrown a rental apartment Upper West Side, she quietly donated money for a down payment on a brownstone in West 13th Street in Greenwich Village. It is a building which, to this day, still belongs to the institute.

ALICE COLTRANE Journey in Satchidananda

Available to purchase from our US store.

Although she credited her husband with introducing her to yoga and eastern religious concepts, Alice made no secret of her debt to Satchidananda, a spiritualist she first encountered in 1969, in the depth of grief. She performed at Carnegie Hall as part of an all-star benefit to raise funds for his Integral Yoga Institute, described in the concert program as a “non-profit, non-sectarian organization” promoting “a synthesis of specific methods which bring the harmonious development of the individual and the peaceful evolution of the community”.

In the heady countercultural ferment of the 1960s and 70s, there was no shortage of Indian gurus in the music world. The Beatles and the Beach Boys found Maharishi Mahesh Yogi for a moment, and George Harrison later found Sri Prabhupada. John McLaughlin and Carlos Santana found Sri Chinmoy. Pete Townshend found Meher Baba. Satchidananda, who came to the U.S. in 1966, had the historical distinction of giving the opening benediction at Woodstock. “Music is a celestial sound and it is the sound that controls the whole universe, not atomic vibrations. Sound energy, sound power, is much, much greater than any other power in this world,” he said, before leading the crowd at Bethel in a chant. A physically striking and charismatic presence by many accounts, his coterie of famous devotees included Carole King, the artist Peter Max, the actor Raul Julia and more. “He was easily the most beautiful human being that ever walked the earth,” recalled Tulsi Reynolds, who played tamboura in her band that evening at Carnegie, and also appeared on “Journey in Satchidananda” and “Universal Consciousness.” “He was absolutely breathtakingly beautiful and he looked like – if you were to imagine what God looked like – he looked like Swami Satchidananda.”

Before he was an orange-robed monk with a flowing beard, Swami Satchidananda was Ramaswamy Gounder, a businessman, husband, and father of two children from Chettipalayam, a small town in Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state in India. Born in 1914 to a family of wealthy landowners, Gounder had worked in his family’s car business, in the film industry, and managed a temple. In a striking parallel to Alice’s own history, Gounder’s full-time spiritual quest was prompted by the death of his wife, which occurred five years into their marriage. He left his sons with his mother, renounced secular life, and departed on a journey through India which culminated with his initiation into monkhood by Swami Sivananda, who gave him the name Satchidananda, meaning ”existence-knowledge-bliss absolute.”

Alice was drawn to the universality of Satchidananda’s teachings, which promoted the idea of divine unity beyond the particularities of religious difference – sentiments which echoed her late husband’s values. But the swami’s most useful and enduring lesson, according to Alice, was pragmatic advice on how to approach work. Her anguish in the wake of her husband’s death had been amplified by the responsibility of dealing with the enormity of the work he left behind. There were the unfinished releases that she would have to oversee, and the bigger picture questions of where to take his musical ideas. “[John] said to me just a few days before he died that I should go ahead and do this myself,” she told Newsday in 1968.

Almost immediately after John’s death in 1967, Alice had established the Coltrane Recording Corporation, which also brought forth the label, Coltrane Records, to do just that. She worked late nights in the studio in the basement of their Dix Hills home, a studio that John had dreamed of but did not live to use himself. (Roy Musgnug, Alice’s in-house engineer who helped build the Dix Hills studio, reports that by the time construction began, John was still alive, but ill, either in the hospital or upstairs with a caretaker, so Alice managed the studio buildout.) “I learned to edit and work the control board by watching the engineers that recorded me…Now I have about 17 privately recorded albums my husband did, in addition to having two albums of my own to do so I have to put the children to bed and come down late at night to practice and work,” she said.

In 1968, her company succeeded in realizing two major efforts: the release of the album “Cosmic Music,” featuring archived recordings with John and herself, and the staging of a concert at Carnegie Hall called “Cosmic Music”, which also balanced her own compositions with those of her late husband.

But the combined responsibilities of running a label, producing concerts and records, and raising a family all proved to be too much. “I had a small staff of people working with me, but they were incompetent and I had to do all of the work,” Alice told Newsday in 1970. “So when a recording company offered me a contract that would allow them to produce John’s private sessions that I edited, I accepted and closed the company.”

It was Satchidananda who Alice would credit with helping her cope with crippling pressure of her workload, while still enabling her to be productive. His advice to her was to practice non-attachment in her working life. “Say, if you want to build a ship, build it in a detached manner,” she later recounted in a 2002 interview published in The Wire. “Don’t build it subjectively, don’t build it by putting your full faith into a technical, temporary, mundane, or materialistic thing. Go about it in a detached way. Detached doesn’t mean disliked, it just means that I don’t want this project to consume me. It will if I allow it. If I subject myself it ends up binding and controlling me. I can’t sleep at night because that’s all I’m concerned about. So I will go and do my work objectively. That’s one of the best lessons I’ve learned that he taught us.”

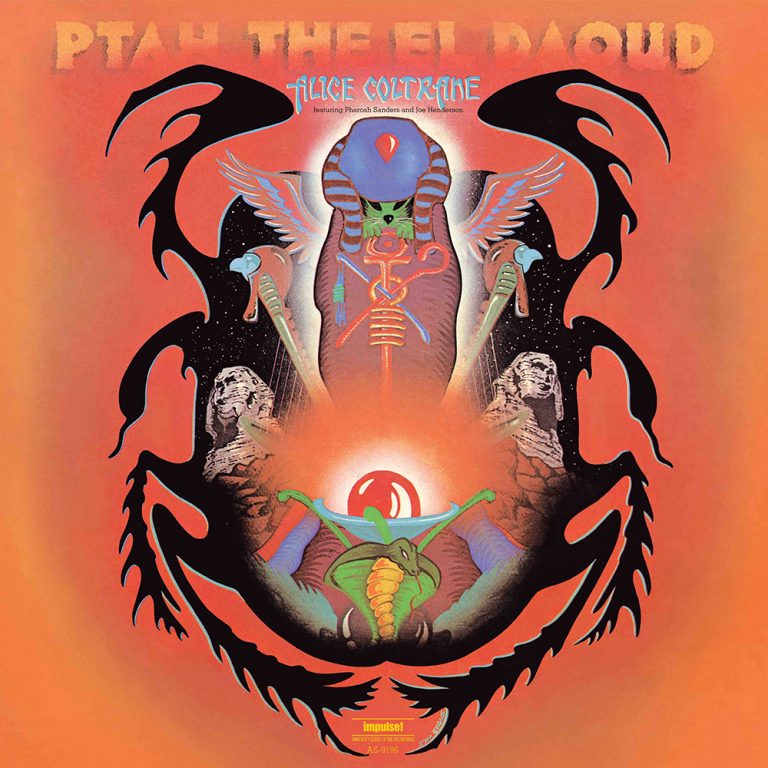

It was a lesson that yielded immediate results. A tour through her discography reveals that she was stunningly active and creatively adventurous from 1970 to 1972 – years she was most involved in Satchinanda’s spiritual community. Albums recorded during these two years alone included “Ptah the El Daoud,” “Journey in Satchidananda,” “Universal Consciousness,” and “World Galaxy “– landmark albums that solidified Alice as a formidable bandleader and saw the evolution of an increasingly distinctive stylistic voice as she experimented with new sounds, including the Wurlitzer and instruments typical to Indian devotional music like the tamboura and harmonium. During these years she also recorded guest appearances on albums by Laura Nyro, The Rascals, and McCoy Tyner, and was heavily involved in preparing and developing her husband’s recordings for posthumous release. These were years that could have easily been lost in a creative and emotional sinkhole, and instead, they became the most focused and prolific of her recording career.

ALICE COLTRANE Ptah The El Daoud

Available to purchase from our US store.It was a fairly cold night on Sunday, February 21, 1971 in New York City. The temperature was hovering around 42 degrees by show time. One might imagine an assortment of suede jackets and fur-lined coats worn by the crowd that evening, filing out of subway stations and up to the Carnegie Hall box office on the corner of Seventh and 57th Avenue. Ticket prices were a flat $6, all sold at the door.

In the weeks leading up to the show, the following advertisement had appeared in The Village Voice and The New York Times:

SID BERNSTEIN presents

A Benefit Performance

Net Proceeds to

INTEGRAL YOGA INSTITUTE

LAURA NYRO

THE RASCALS

ALICE COLTRANE

Featuring

PHAROAH SANDERS

To the casual concertgoer who spotted the ad in the Village Voice, the lineup might have presented an intriguing collage of acts from seemingly disparate scenes, but those on the inside knew that Laura Nyro, The Rascals’s Felix Cavaliere, and Alice were all disciples of Satchidananda. Indeed, they had all travelled together to Ceylon a few months prior.

Like many other rock and folk performers at the time, Nyro and especially The Rascals were stylistically edging closer towards jazz, with Alice appearing on both of their most recent or forthcoming projects. While Alice’s music stood apart from the rest, the evening’s kaleidoscopic programming was in tune with the zeitgeist, with massive festivals like Newport Jazz, Isle of Wight, and Amougies juxtaposing jazz, rock, and pop acts on the same bill. Even as genre-specific an organ as DownBeat had added the words “blues” and “rock” to its cover logo. Intrepid rock promoters including Bill Graham, Steve Paul, and, to an extent, Sid Bernstein were also responsible for this shift.

Bernstein, who presented the show that night at Carnegie, was a Satchidananda follower at the time. He was a little older than either Graham or Paul and unlike them, was a general impresario. He booked a variety of entertainment, including open chess matches and also managed The Rascals. He was best known for presenting the Beatles in New York City for the first time at Carnegie Hall. Marketing materials for the show, including ads and the concert program, prominently featured his branding at the top.

Cavaliere recalls that the audience was diverse and not necessarily all young. “I remember it was a fun night. People in New York, they’re more rounded. Certainly they were more open, not locked into some of the things that are going on today. So it was a great, diverse crowd. Carnegie Hall wasn’t exactly cheap to get into so that limited the audience. There was a lot of grey there, way before my generation, but like our generation turned grey. For example, Laura had this fantastic grandfather who was an older man and he came and man, he adored her.”

“[The audience was] in bliss. I mean, seriously. The spirit of that event took hold from the beginning, There was no doubt. They were all devotees or interested people in the higher levels of consciousness. No question about it. ”

With the diverse crowd came divergent values. Laura Nyro opened the evening, just voice and piano, and during her 20-minute set, according to her biographer Michele Kort, she gave a “surprisingly long rap about the guru”, telling a story about asking Satchidananda for advice on how to get a man to fall in love with her. “You have to be his woman and his lover, you have to be his best friend, you have to be his sister, you have to be his mother, you have to be his maid,” she paraphrased the guru. “…and then he wouldn’t need any other woman.” “Bullshit”, someone shouted, to which Nyro replied, “You may think it’s bullshit, but I think it’s true,” a retort that garnered applause.

Alice’s set followed and the shift in her spiritual focus became obvious. Her 1968 Carnegie concert had been dedicated to the more universal “Cosmic Beloved Lord.” Her 1971 performance situated her within a specifically Vedic context — in sound and message. Her band that evening added two members of Satchidananda’s circle — Kumar Kramer and Tulsi Reynolds, playing harmonium and tamboura, respectively — to a large jazz ensemble comprising two saxophonists (Sanders and Archie Shepp), two bassists (Jimmy Garrison and Cecil McBee) and two drummers (Ed Blackwell and Clifford Jarvis). It was essentially an enhanced double quartet – a configuration made famous by Ornette Coleman’s “Free Jazz” and Miles Davis’s “Bitches Brew.” (At that point Sanders’s star was shining bright, and his name appeared as featured artist on both the evening’s set and on the cover of “Journey in Satchidananda.”)

Though there had been no group rehearsals, Sanders, McBee, and Reynolds had played together on the “Journey in Satchidananda” session in Dix Hills the previous November. The inclusion of amateur musicians whom Alice met through her new spiritual community didn’t immediately sit well with Sanders, though he grew more comfortable as they got going. “Pharoah gave me a dirty look, and Alice said, ‘Pharoah’ – and he stopped it,” recalled Tulsi, a singer by training from Brooklyn, who had taken up the tamboura as part of her study of vocal raga.

At Carnegie, Alice structured her set in a dramatic crescendo, opening with two new compositions, “Journey in Satchidananda” and “Shiva-Loka”, priming the stage in ethereal, meditative colors. She then switched from harp to piano, an instrument change that enabled the set’s shift into a high-energy register on “Africa” and “Leo”. Both were songs out of John’s book that served as points of departure, allowing players to stretch out in open-ended improvisation beyond the limits of time signature and formal song structure.

“Leo” was a tune Alice played with John after joining his band. “Africa”, too, had special significance, as it appeared on “Africa/Brass,” an album which, as an old friend from Detroit, reed player Bennie Maupin recalled, had fascinated her since its initial release. Performing John’s music was a way to still connect with him. “The feeling that I get from playing his music is sort of a sharing, you know, with him,” she said. “It’s sort of a being with him on a mental plane or on a spiritual plane.” Although Alice had been cautioned to keep her set to 20 minutes, the first song alone lasted that long.

Cavaliere, who led the Rascals in the set that followed Alice’s performance, was amazed by the music and virtuosity he had witnessed. “I kind of remember the spaciousness…I’m sure the audience was a little overwhelmed because it was kind of hard to figure out what exactly was happening up there. I think they ran out the chord changes and that’s about it — they just went and the good thing about it is that they had the chops. You gotta be a trained musician. If you’re not, that’s the wrong genre for you because you gotta really know a lot of scales.”

Cecil McBee offers his onstage perspective: “The spirit was there at all times…there was a feeling in that room that called for you to be yourself, and play and answer to what was expected of you.” He recalls that Alice’s “serious intent to express something”, coupled with the expectation that band members express themselves freely within a minimal, intuitive framework, made the evening a heavy musical experience. “It was 150 percent seriousness to find, to provide the platform so that one collectively could uniquely put forth who they were, without expectation…that’s pretty hard to achieve.”

McBee had met Alice around 1962, when, after his military service, he briefly touched down in Detroit for a year before heading to New York. He attended a few Sunday jam sessions that she hosted in her home. “She had a big Victorian house with a large living room and a lot of space and a grand piano in the centre of that room. It was sort of common for folks who were local and those who were passing through to join everybody there at about one in the afternoon on Sundays and play until about 7 or 8,” he said, adding that the sessions drew the likes of Elvin Jones and Barry Harris. McBee describes Alice as serious and private, and recalled that there was not much, if any, small talk with her. “There was really no camaraderie for the most part,” recalls McBee. “Alice was a very personal, serene, tender, gentle person that presented herself to you in very serious fashion pertaining to the music. But after that she was gone.” Similarly, Archie Shepp had no idea that Swami Satchidananda was Alice’s guru until years later, when he was reading liner notes on an album. But like McBee, Archie easily recalled the spiritual message in her playing. He described a “feeling of the church in her music,” which he attributed to her Detroit background and particular manner of voicing chords, which, as he said, “evok[ed] something very spiritual in the performer.”

Listening back to this live performance today, McBee says, “I’ve never heard anything that I played that was that more intense, that intense and that well designed as improvisation is concerned. It was absolutely amazing.”

The concert accomplished its immediate purpose, raising $8,000 dollars [equivalent to $61,000 in 2023] for Satchidananda’s rapidly expanding Institute, which between 1970 and 1972 grew from one New York City apartment to 25 centres across North America and Europe. Reviews of the evening were overwhelmingly positive, with a special emphasis on Alice’s set. “[Her group] was one of the greatest assemblages to appear on the Carnegie Hall stage,” raved Billboard’s Bob Glassenberg.

Others underscored the broad appeal of the billing. “There was something for everyone on this program,” wrote Joe H. Klee for Downbeat. “The underground people had their love goddess, Laura Nyro. The teenage rock ‘n’ roll dance freaks had their Rascals, and jazz fans had Alice and Archie and Pharoah…I doubt if anyone present enjoyed all three of the diverse acts equally well, but nobody went away disappointed.” Klee singled out the performances of “Africa” and “Leo” in his review, calling it “some of the finest improvisational music that’s been played since Trane checked out in 1967.”

At the time, Ed Michel, then head A&R at Impulse Records, was aggressively peddling Alice’s music to audiences outside of jazz, through college and freeform radio. “I think one can say that the FM listener got into this music through people like Jimi Hendrix,” he told Billboard in 1971. “The high-energy people. Somehow there was a transfer from that type of energy to the similar vibrations put out by John Coltrane. Then the people got to Alice Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders and Archie Shepp.”

Michel supervised the recording of Alice’s 1971 Carnegie Hall performance with the intent to release it. For various reasons. it was not, and the full performance is now being released for the first time. As Michel notes in his essay, though there had been significant challenges with sound — such as a shortage of microphones, which led to the tamboura and harmonium not being separately miked — Michel had called on an expert sound technician: Dave Jones, the engineer responsible for Bill Evans’ legendary Sunday at the Village Vanguard album.

For Alice, the 1971 Carnegie Hall concert had been a display of how well her music worked outside of the jazz circuit, particularly to a spiritually-minded crowd. “My music isn’t jazz, not really,” she said in an interview later that year. “It is closer to spiritual music. It’s universal and it’s freedom.” The performances on “Alice Coltrane: The Carnegie Hall Concert” served as a sign of things to come, a chronicle of an artist in the midst of a musical and spiritual emergence. It struck a balance between meditative songs inspired by Vedic devotional songs and the more intense energy and open-ended structures she had been exploring in John’s last lineup. It also prefigured her eventual turn towards playing music exclusively for a spiritual community, save for the exceptional opportunity to play music with her children, or pay tribute to her late husband.

The summer after the 1971 Carnegie performance, Alice went on the road with Satchidananda, joining him and Peter Max on a trip to Chicago, where they appeared on a televised talk show and she performed at another benefit for the Institute. But by 1972, she had moved to California, and no longer considered herself a follower of Satchidananda, seeing him from then on only for occasional visits or performances. That same year, Satchidananda found himself mired in controversy for his relationships with his students; a guru who, like many others, proved to be all too human.

Alice had begun to use the name Turiya, signing her name as “Turiya Aparna” on the gatefold of her album “Universal Consciousness.” By 1976, she had become a swamini herself and taken the name Turiyasangitananda (Sanskrit for “the Transcendental Lord’s highest song of bliss”). It was a name that signalled her full withdrawal from secular life.

“My children, I had raised them, my husband had passed some years ago,” she told her biographer, Franya Berkman. “I had reached a point where most of my duties as a householder were fulfilled. It gave me the time to want to see, to want to strive, to want to devote quality time, because, you know, the work of a woman is so full! I mean it’s sometimes twenty-four hours. So once that was reduced, I had additional time that I could apply to the path, and that’s what I’ve been doing.”

In 1982, she founded the Sai Anantam Ashram in Agoura Hills, California, northwest of Los Angeles in the Santa Monica mountains. She was no longer a student. Her relationship with Satchidananda had become one of equals. “He was a great person and a great yogi. He gave the best lectures, and he was very universally minded,” Alice stated in 2003. “I didn’t seek any spiritual guidance from anyone else after him.”

ALICE COLTRANE Kirtan: Turiya Sings

Available to purchase from our US store.Read on…The Art of Jazz Harp

Lauren Du Graf is a writer and producer based in Seattle, Washington.

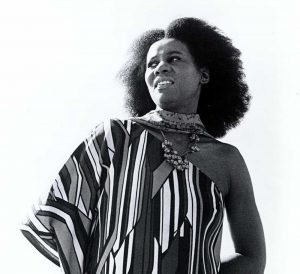

Header image: Alice Coltrane. Circa 1970. Photo: Michael Ochs Archives via Getty.