Tracing the roots of jazz is as complex as the founding of America itself. Much like our nation, jazz is an amalgamation of experiences and influences that shape its overall sound and style, and it continues to evolve into the 21st century. Jazz embodies the Black American experience – from the Transatlantic Slave Trade to Jim Crow – blending European instrumentation (brass, piano, woodwinds, and double bass) and harmonic structures with the lush, intricate rhythms of the Caribbean.

Long before big bands dominated the Swing era, the late 19th and early 20th centuries laid the groundwork. Between 1880 and 1925, the blues and gospel of the South, the ragtime of the Midwest, and the collective improvisation of early New Orleans bands would converge, creating what we now call jazz and radically changing how we approach and listen to music.

Blues & Gospel

The blues and gospel form the emotional bedrock of modern music, influencing virtually every genre, including hip-hop, rock, pop, and R&B. Spirituals originated in hush harbor gatherings, where enslaved Black people secretly congregated at night in secluded places, often outdoors, to worship and find solace away from their enslavers’ control. During these gatherings, they employed techniques like whispers and coded songs as acts of resilience and resistance against their oppressors. Combining African oral traditions with Christianity, hush harbor meetings laid the groundwork for the Black church.

By the late 1880s, this spiritual tradition had evolved into secular work songs and field hollers that expressed the struggles and hardships of everyday life. Often considered “two sides of the same coin,” both gospel spirituals and the blues share many features: a 12-bar structure, vocal techniques such as wailing, moaning, melismas (vocal runs) and call-and-response.

In gospel, call-and-response mirrors the African oral tradition, where the pastor or lead singer “calls out” or sings a line, and the congregation or choir responds. However, in the blues, call-and-response can occur between two contrasting voices or between a singer and an instrument, often a slide guitar, harmonica, or a full band. From bending notes to rallying cries, both gospel and blues position the singer as the “messenger” or storyteller.

Two blues styles greatly influenced early jazz:

The Delta Blues, originating in Mississippi, focuses on solo performances and is often richer in texture and tone, emphasizing raw energy and improvisation while allowing ample space for emotional expression. Notable Delta Blues artists include Robert Johnson, Elmore James, Skip James, John Lee Hooker and Lead Belly.

Vaudeville or Memphis Blues produced some of our earliest known feminists – Ma Rainey, Ethel Waters, and Bessie Smith – who toured and performed on the vaudeville circuit, either through the Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA), which was notorious for low wages, or its contemporary, the Chitlin’ Circuit, which nurtured Black talent at the height of Jim Crow. Widely regarded as the Father of the Blues, W.C. Handy composed such standards as “St. Louis Blues” and “Memphis Blues,” and published his work, which codified and helped popularize the genre across the country.

Ragtime

If gospel and the blues provided jazz with its inherent soul, then ragtime would give it rhythmic precision and form. Emerging from Missouri in the 1890s, ragtime featured syncopated rhythms and distinctive melodies over a steady bass line, chiefly in piano music. Syncopation is when musical rhythm places emphasis or accents on unexpected or “off-beats,” disrupting the regular, steady rhythm. In a 4/4 song, syncopation stresses the “2 and 4,” or the parts between the main beats, creating a “ragged,” funky groove.

The three most prominent composers of ragtime were James Scott, Joseph Lamb, and, of course, Scott Joplin. Dubbed the King of Ragtime, in his lifetime, Scott Joplin composed over 40 ragtime pieces (often called “rags”), two operas, and a ballet. After he performed at Chicago’s World’s Fair, ragtime turned into a nationwide sensation.

Joplin began publishing his music in 1895, garnering fame and a steady income, notably from the sales of “Maple Leaf Rag,” widely considered the archetype of ragtime. Ragtime and stride piano would inspire classical musicians of the era — Stravinsky, Satie, Debussy, and Ives. With its multi-strain structure, listening to “Maple Leaf Rag” reveals four contrasting sections, each with 16 measures, arranged in an “AABBACCD” pattern, and features syncopated melodies. Multi-strain compositions taught musicians how to organize larger works, repeat ideas, and build momentum — skills essential for early jazz figures like Jelly Roll Morton and Fletcher Henderson.

New Orleans

A port city with African, French, Spanish, and Caribbean influences, New Orleans has long been a vital cultural hub and the birthplace of jazz. Following the Haitian Revolution, New Orleans experienced a significant influx of enslaved and free people of color. Haiti’s victory over France forced Napoleon to abandon his plans to acquire American territory, leading to the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the nation’s size and formed 15 additional states.

New Orleans’ expanded territory and increased population would influence its architecture (shotgun houses), cuisine (okra & red beans and rice), Mardi Gras celebrations (rara sounds in Krewe du Kanaval), and, of course, music (improvisation and rhythmic timing). Congo Square is another crucial element of the development of early jazz.

Located in Louis Armstrong Park in Tremé, Congo Square was a gathering space for enslaved people of color to play music, sing, dance, and set up a marketplace. Much like hush-harbor meetings, Hoodoo practitioners would hold midnight spiritual ceremonies with ring shouts, calling upon the ancestors for healing and fortitude in Black communities.

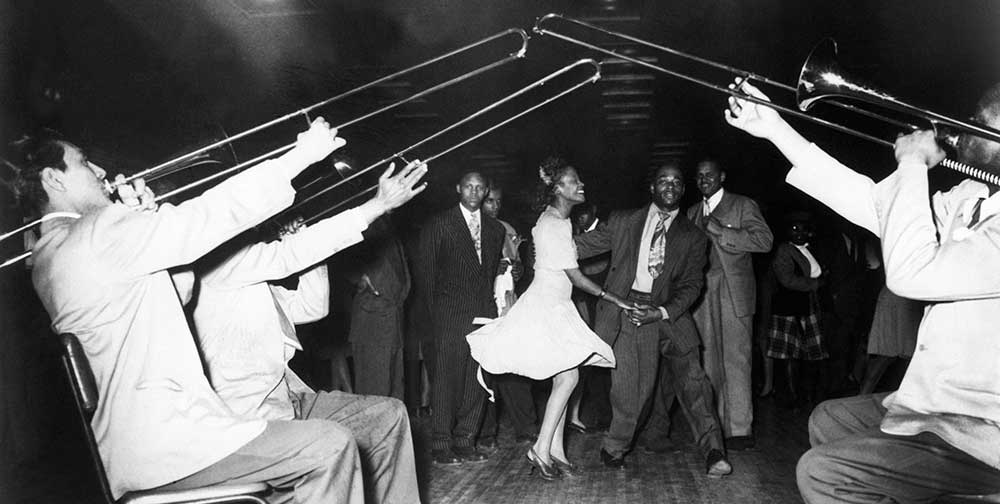

By the late 19th century, Congo Square would become a venue for brass band concerts from local orchestras in the region’s Creole of color community. New Orleans jazz was defined by collective improvisation. Furthering the tradition of call-and-response, the cornet relays the melody, the clarinet “responds” with a countermelody, and the trombone provides a low glissando (growl), lending the tune its rhythmic and harmonic foundation.

Vocal-like techniques, such as glissandos, were pioneered by legendary trombonist Kid Ory. Early New Orleans jazz was a three-part polyphony, backed by strings (banjo, guitar), string bass or tuba, and drums, creating a multi-layered, vibrant sound that captures the spirit of the city. Second line parades and funeral marches keep this tradition very much alive. Other trailblazers who were pivotal to honing New Orleans’ jazz include:

Cornetist Buddy Bolden, who combined the blues tradition with ragtime;

Pianist and bandleader Jelly Roll Morton, cited as the genre’s first arranger, who would also blend the precision of ragtime with improvisation and introduce the “Spanish tinge,” drawing influence from the Caribbean rhythms;

Cornetist and bandleader King Oliver introduced mutes to jazz. His jazz ensemble, the Creole Jazz Band, brought New Orleans jazz to Chicago and became one of the most influential bands of the 1920s. Members of the ensemble included reedist Johnny Dodds, his younger brother, drummer Baby Dodds, and Louis Armstrong, who famously said that jazz would not be what it is without King Oliver;

Sidney Bechet is celebrated for his intensely expressive solos on clarinet and soprano saxophone. His emotional intensity captivates listeners, foreshadowing the transition from group improvisation to solo virtuosity.

Shannon Ali (Shannon J. Effinger) is a freelance arts journalist and cultural critic. Her writing on jazz and music regularly appears in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian, NPR Music and Pitchfork, among others.