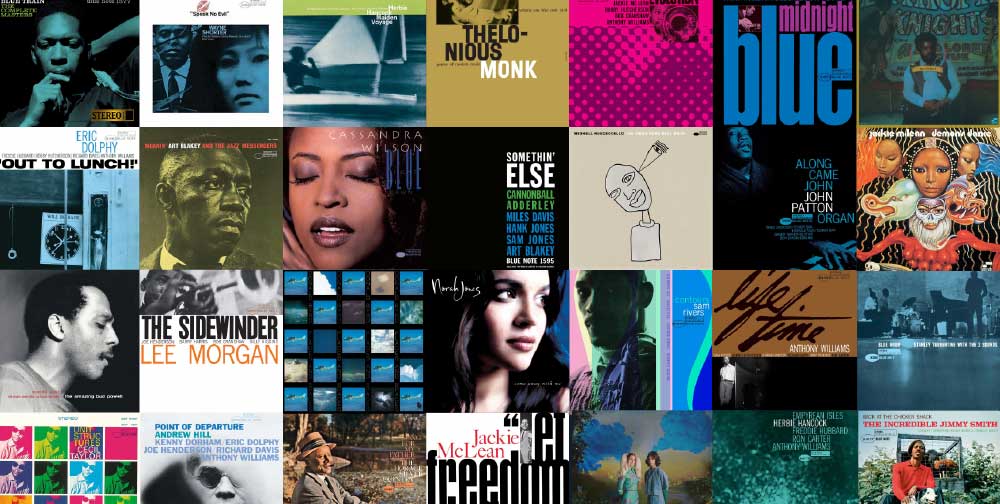

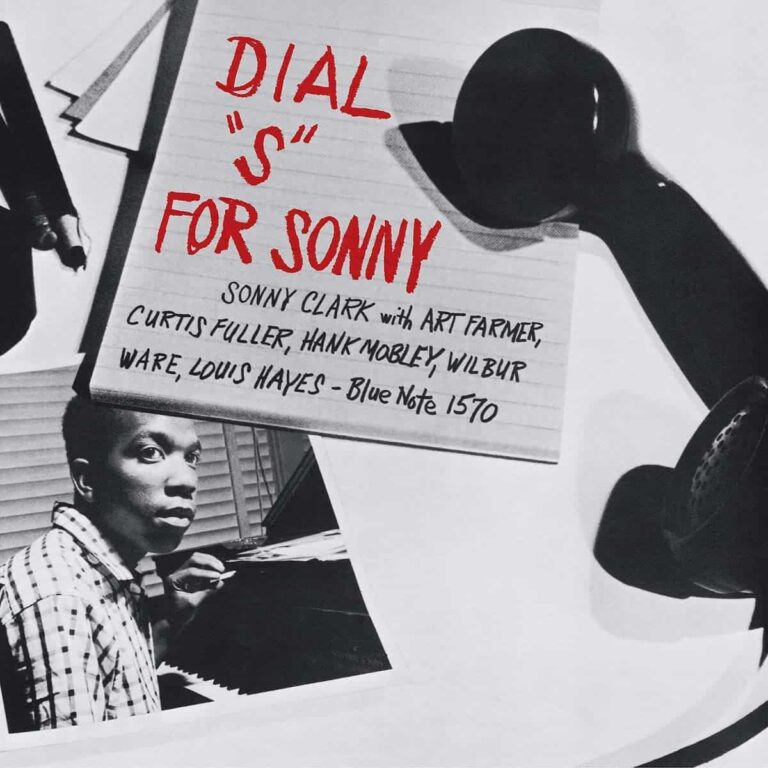

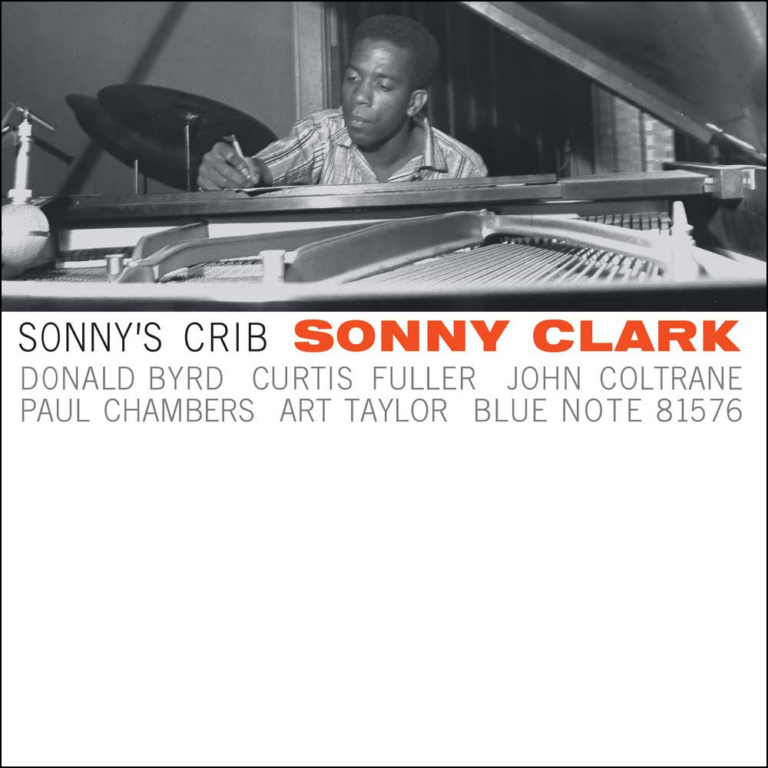

When Sonny Clark turned up to Rudy van Gelder’s studio in September 1957 to record “Sonny’s Crib”, the pianist had already amassed years of experience, despite his carefree, youthful optimism.

SONNY CLARK Sonny's Crib

Available to purchase from our US store.Moving from Pittsburgh to the West Coast and then to New York City in the early to mid-1950s meant that Clark had plenty of styles in his songbook. He soaked up bebop before adapting to California’s laid-back, chamber-esque jazz in Buddy DeFranco’s quartet, which allowed him to put a personal twist on the sounds that were emanating from the hotbed of hard bop. Clark had distilled his favourite elements of piano idols Bud Powell, Horace Silver, Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson, and shaped them into his own image – fluent and swinging, carefree yet bluesy, cooking but cool.

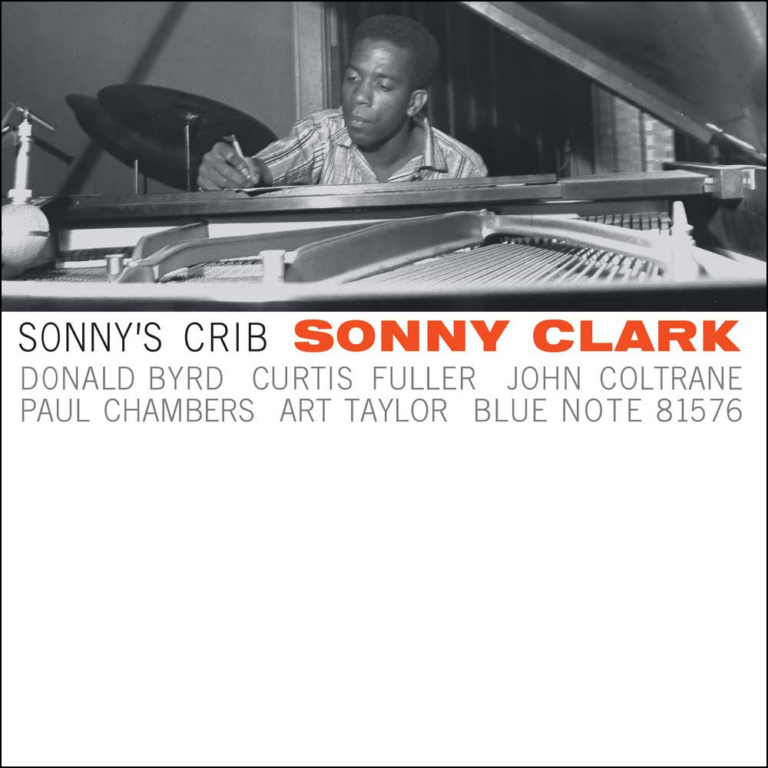

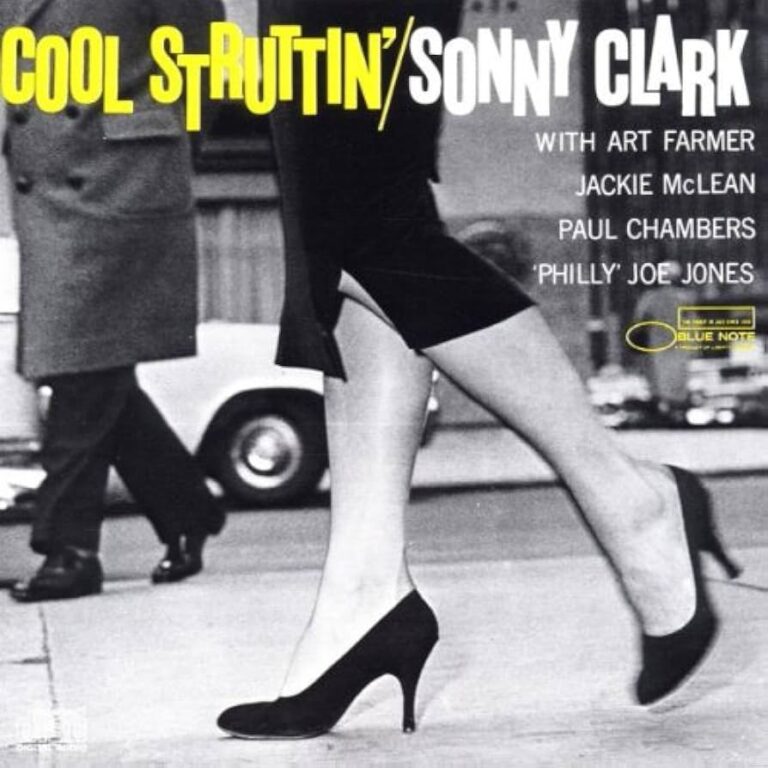

When Clark arrived in New York in 1957, he quickly struck up a rapport with Blue Note co-founder Alfred Lion. Clark already had a reputation for never playing a bad session, and his debut album “Dial “S” for Sonny” proved that with ease. However, it was his follow-up albums, “Sonny’s Crib” and “Cool Struttin” just four months later, that saw him up the ante and deliver two recordings that are now considered bonafide hard bop classics.

By the time he came to record “Sonny’s Crib”, Clark was right in the thick of it – trading licks with Thelonious Monk at the home of jazz patron Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, playing with Charles Mingus and Sonny Rollins. That year, he recorded so many sessions for Blue Note, he was practically their in-house pianist. For “Sonny’s Crib”, Clark wanted the best of the best, with a combination of tonal colours and improvising personalities that would really bring the music to life.

SONNY CLARK Cool Struttin'

Available to purchase from our US store.

SONNY CLARK Dial 'S' For Sonny

Available to purchase from our US store.Clark kept the same sextet configuration from “Dial “S” For Sonny”, but opted for a change of personnel. He kept Curtis Fuller and his rich trombone timbre, and went for two of the most exciting trumpet and tenor players of the moment – Donald Byrd and John Coltrane. It was a line-up that would anticipate Coltrane’s own quintet with Red Garland later in the year, and when Clark learnt that Coltrane was looking to get Curtis Fuller on his own “Blue Train” album, the jigsaw pieces fell into place.

Clark had heard Coltrane playing with Miles, and he’d been spellbound. He hoped the session would be a chance to get to know Coltrane better, but when Clark tried to engage him in conversation, he found Coltrane even more reserved than he’d expected. However, it was an auspicious sign for the eloquent music that was to come.

In search of the perfect rhythm section, Clark looked no further than bassist Paul Chambers and Art Taylor on drums. The young Chambers and Art Taylor had played together as part of Red Garland’s trio, and had a dynamic intimacy, knowing exactly how much supportive space to leave for Clark’s piano, while propelling the group forward.

Clark chose to record a selection of three popular tunes of the day and two originals, and they are all rather unconventionally arranged. As Leonard Feather notes, “there are no fours at any point… there are enough 32s, 64s and even 128s to provide a maximum of improvisation and inspiration.”

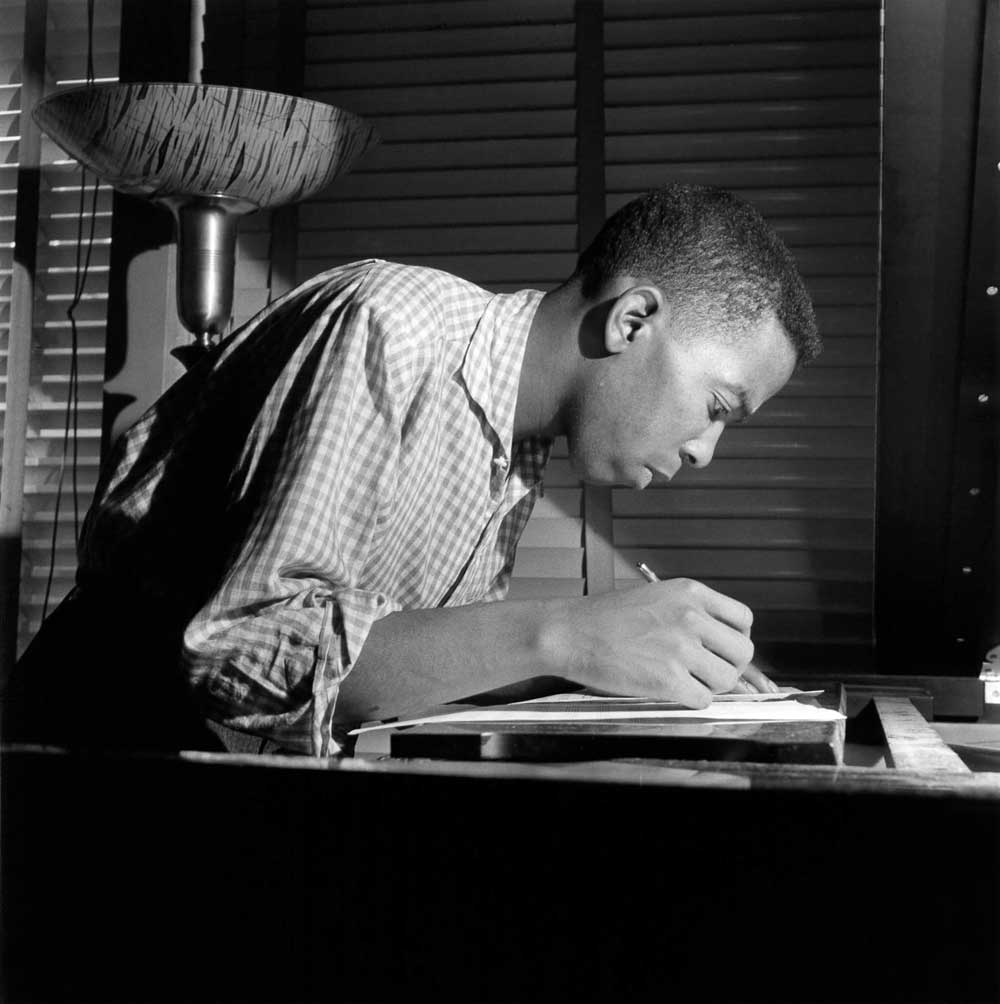

Indeed, the album cover depicts Clark sitting at the piano, pencil in hand, adjusting the charts. He refined the arrangements by stretching out the solos, giving each player enough space to fully develop their improvisational ideas, particularly on his own tunes “Sonny’s Crib” and “News For Lulu”. This was hard bop as Clark intended, his musical playground, elongated to accommodate as many improvisational ideas as possible.

“Sonny’s Crib” is fascinating for a number of reasons. Not only is it a stellar line-up that gels amazingly well, it also captures each of the players at a certain moment in their oeuvres, particularly Coltrane and Byrd. Coltrane proves he is light years ahead in his development as a soloist, shortly before his own recordings for Blue Note and his paradigm shift to modal jazz. Byrd is an ambitious 25-year-old who is about to embark on a career-defining run of albums for Blue Note the following year. He has plenty to say and is brimming with energy.

We can only imagine what Clark might have gone on to create, as modal and free jazz were emerging. He succumbed to the spiral of substance addiction until his death in January 1963, aged 31. Clark reportedly died at Junior’s Bar on 52nd and Broadway, a few blocks from Carnegie Hall – but the bar manager moved his body to a nearby flat to avoid the bad publicity. Despite the support of Pannonica de Koenigswarter, Clark’s death was tragically mishandled. The baroness had arranged for his body to be shipped to Pittsburgh to his family, but due to a mix-up, the wrong body was transported and Clark’s never recovered.

SONNY CLARK Sonny's Crib

Available to purchase from our US store.Despite posthumous releases, Clark’s albums were long overlooked until a reappraisal in the 1970s, led by Japanese fans, finally saw his work getting the acclaim it deserved. “Sonny’s Crib” is a prime slice of Clark’s genius, and how he helped define the whirlwind of jazz creativity in New York through the late 1950s into the very early 1960s. For the short time he was a part of it, one of its brightest stars.

Max Cole is a writer and music enthusiast based in Düsseldorf, who has written for record labels and magazines such as Straight No Chaser, Kindred Spirits, Rush Hour, South of North, International Feel and the Red Bull Music Academy.

Header image: Sonny Clark. Photo: Francis Wolff/Blue Note Records.