Don Cherry originally rose to fame as part of Ornette Coleman’s first quartet in the late 1950s. Born in Oklahoma and raised in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, the trumpeter – who often played cornet, or pocket trumpet – joined the group in 1957, then still a quintet with pianist Paul Bley. Cherry was present on Coleman’s most influential early recordings, including the breakout album “The Shape of Jazz to Come” (1959) and the genre-defining “Free Jazz” (1961).

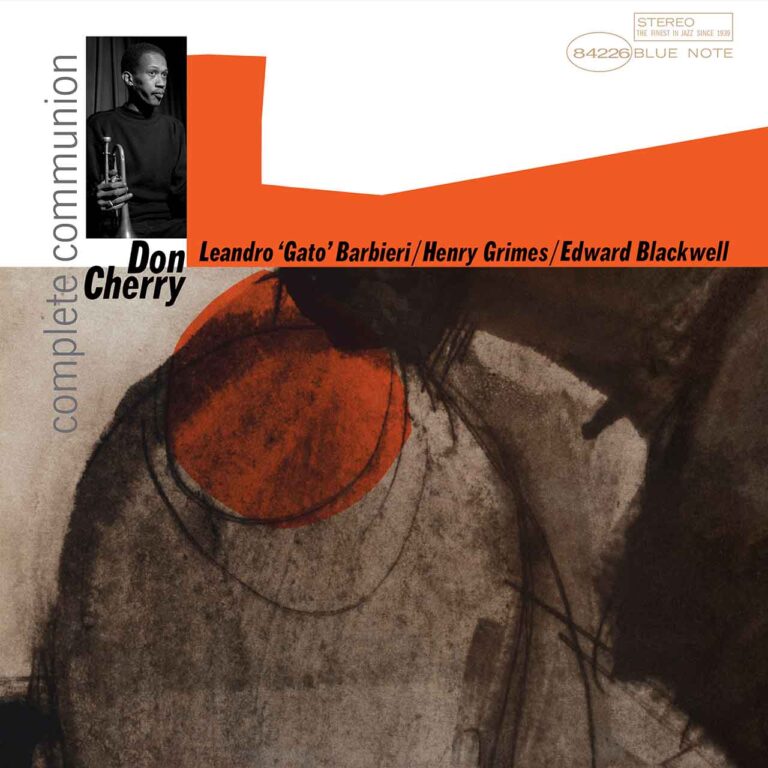

DON CHERRY Complete Communion

Available to purchase from our US store.In 1960, he recorded with John Coltrane; material from the session was released six years later, ineptly titled “The Avant-Garde”, as it felt rather tame and restrained in comparison to the music he’d made with the Ornette Coleman quartet. During the first half of the 1960s, Cherry joined Sonny Rollins’ group as the bebop legend turned towards freer forms of jazz. He also played and recorded with other young proponents of the “New Thing” such as Archie Shepp, John Tchicai, and Albert Ayler.

Cherry was a nomadic soul, and in the 1970s he’d move to Sweden to found a commune with his Swedish wife Moki. But even back in the early 1960s, he was traveling to Europe frequently to play, assembling a group with improvisers from Germany, France and Italy, and making a deep impact on young European free jazz musicians such as Peter Brötzmann and Evan Parker.

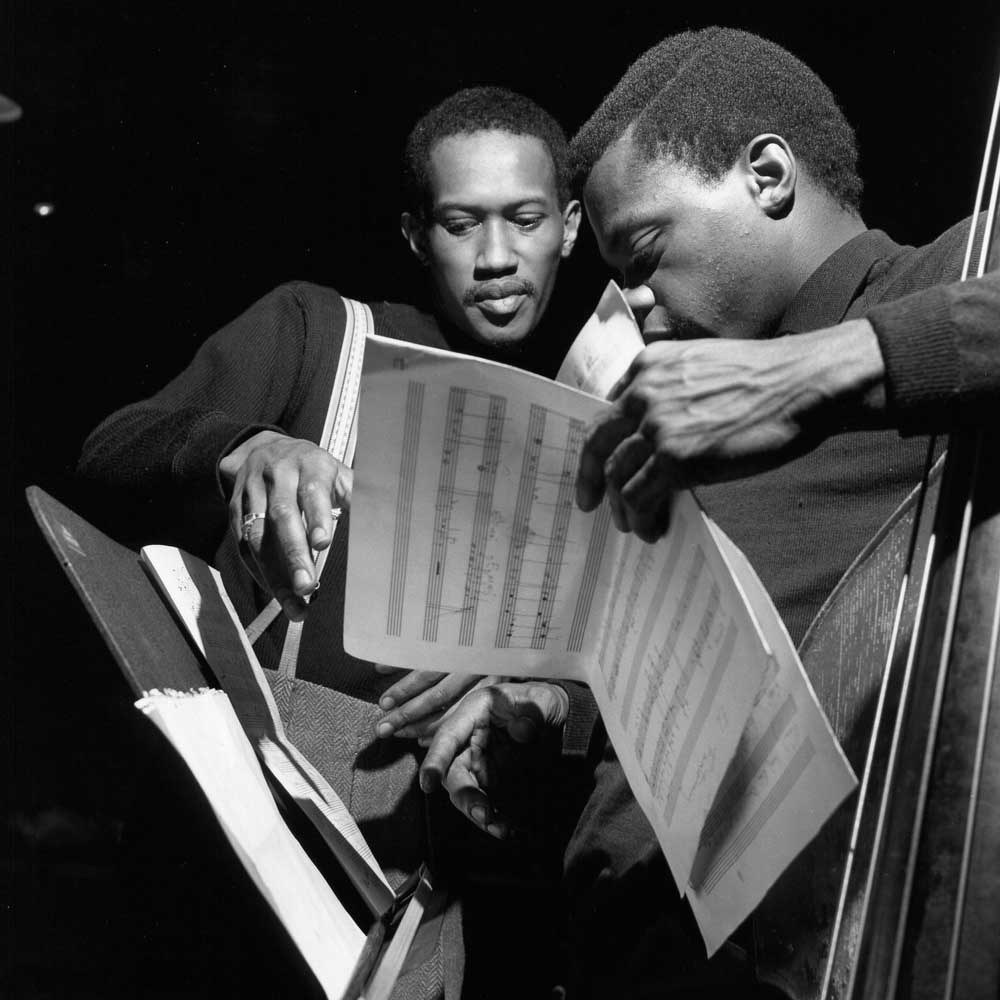

In late 1965, Cherry found himself back in New York City, together with the Argentinian tenor saxophonist Leander “Gato” Barbieri, whom he’d met gigging in Italy. Faced with the opportunity to record a session for Blue Note, he called upon two friends from the city’s avant-garde scene: Bassist Henry Grimes, with whom he’d played in the Rollins quartet, and drummer Ed Blackwell, another former member of Coleman’s group.

That quartet would record his debut as a bandleader, “Complete Communion” (1966), on Christmas Eve of 1965 at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio, and a second Blue Note date, “Symphony for Improvisers” (1967), where it was joined by tenor saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, nine months later. The late German jazz historian Ekkehard Jost rated these two albums “among the most important [LPs] in free jazz of the Sixties.”

“Complete Communion” introduced a new and unheard style of compositional structure to jazz recording. To reflect the music they were playing live, Cherry decided to record two long suite-like pieces of around 20 minutes duration, one for each vinyl side. These suites would follow several “thematic complexes” with a high degree of melodic familiarity, but woven together through sections of live group improvisation. That approach would become standard procedure in free jazz and co-opted in experimental rock music.

Within these new compositional frameworks, the players did not improvise on modes or chords anymore, as in bop and modal jazz, but on the abstract “motivic substance” of the symphonic themes. Unlike John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy, who experimented with “taking trips” from the tonal centre, Cherry often abandoned the modal frame completely; he’d rarely even adhere to the Western harmonics commonly used in jazz, and instead looked towards the microtonality of Indian Classical music or the scales of traditional Arabic music. At the same time, a slight hint of bop was always present as part of his musical identity.

DON CHERRY Complete Communion

Available to purchase from our US store.On “Complete Communion”, every one of the four players gets an equal voice. There is no bandleader, only bandleaders. No soloists, all soloists. It’s a spiritual thing, a communal thing. What makes this complex music so compelling is the non-verbal communication between the musicians. Cherry and Barbieri knew each other extremely well from months spent on the road together, and Blackwell and Grimes formed a bond that Jost aptly calls a “somnambulistic empathy”. All four know the basic material enough to come up with the most unpredictable transitions but always react to each other’s creative ideas in real time with ease.

With the Tone Poet audiophile remaster, this defining album of avant-garde jazz is finally available in a version that sounds as close as possible to the original master tapes of the recording. On the original 1966 pressings, Henry Grimes’ bass was barely audible; this deficit was corrected on later reissues, but as usual, curator Joe Harley and engineer Kevin Gray made sure that listeners will be able to hear for the very first time what really happened in Englewood Cliffs on 24 December 1965.

Stephan Kunze is a writer, book author and a commissioning editor for Everything Jazz. He writes the zensounds newsletter on experimental music and culture.

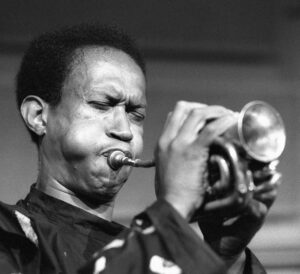

Header image: Don Cherry. Photo: Frans Schellekens/Redferns.