Nonetheless, it’s true to say that, from the mid-1960s onwards, key jazz artists started to make music that was intrinsically bound up in overtly spiritual sounds and ideas, and which has continued to influence successive generations of artists ever since.

John & Alice Coltrane

The foundation is undoubtedly John Coltrane’s masterpiece, “A Love Supreme”. Recorded at the end of 1964, during a period of deep introspection, it was meant as a devotional offering to God – both intensely personal and, simultaneously, a reflection of the wider search for new modes of self-expression and identity experienced by African American artists at that time. For Coltrane, it let the genie out of the bottle, and thereafter his music became more explicitly spiritual at the same time as it became more turbulently aligned with free jazz. “Om”, recorded in 1965, is named after the sacred sound and symbol central to Indian religions and begins with a chanted recitation from the Bhagavad Gita.

JOHN COLTRANE A Love Supreme (60th Anniversary)

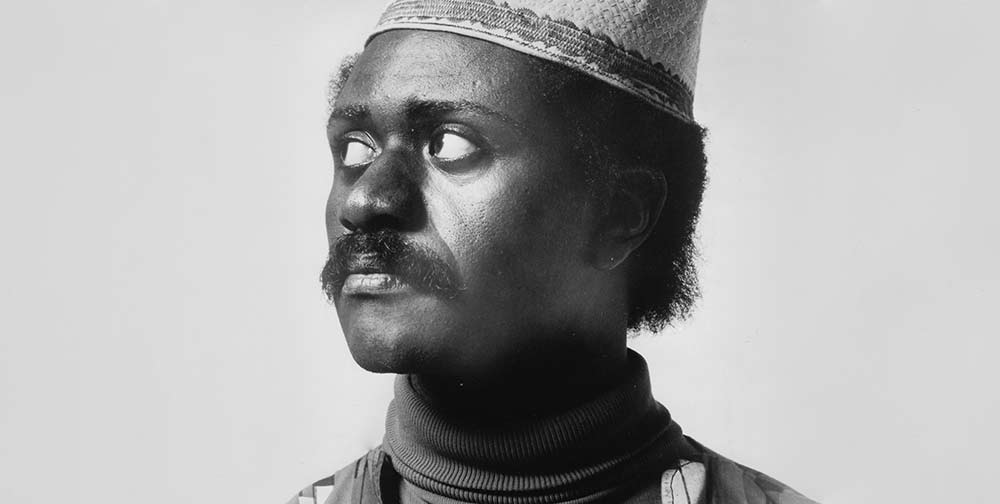

Available to purchase from our US store.After Coltrane’s death in 1967, some of the musicians who had been closest to him sought to continue his mission to forge a deeply spiritual music that explored non-Western sounds and philosophies in an attempt to heal an ailing humanity. Chief among these was his widow, pianist and harpist Alice Coltrane. A devotee of Indian guru Swami Satchidananda, she released a string of albums in the late 60s and early 70s that were increasingly influenced by Hindu Vedic religious traditions. Her 1971 date, “Journey in Satchidananda”, remains an eternal blueprint for the music that has subsequently become known as spiritual jazz: deeply meditative, drenched in the humming drone of the Indian tambura and built around elemental bass vamps.

ALICE COLTRANE Journey in Satchidananda

Available to purchase from our US store.The 1970s

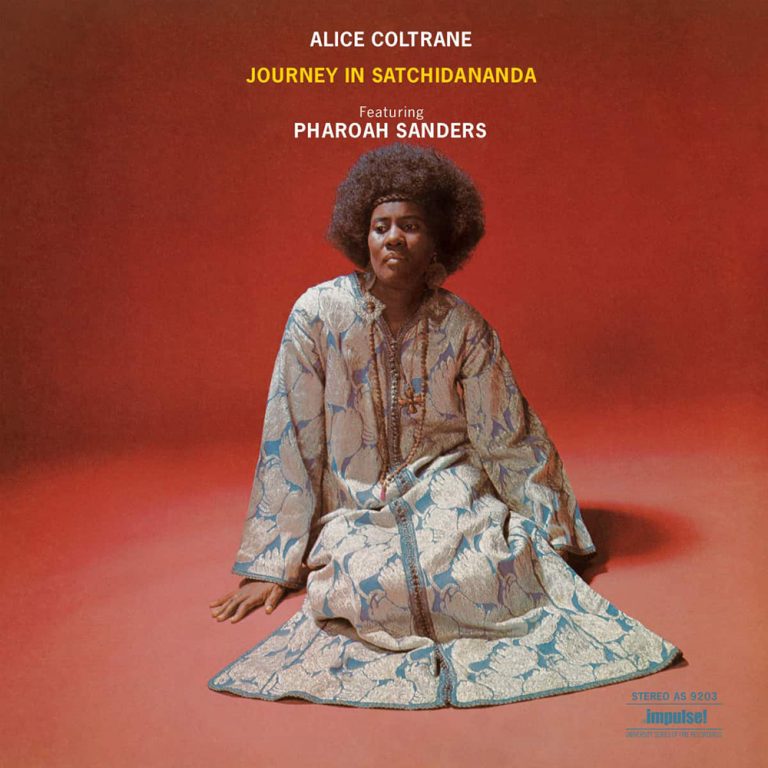

Another cornerstone of spiritual jazz can be found in the works of saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, who played in John Coltrane’s final bands. Albums like “Karma” (1969) – with its central track “The Creator Has a Masterplan” – and “Izipho Zam (My Gifts)” (recorded 1969) were open-hearted declarations of spiritual yearning that combined free jazz with deep grooves influenced by Indian and African music. On “Prince of Peace,” from the latter, vocalist Leon Thomas drops into the repeated lyrical refrain “Hum-Allah,” adding a layer of Sufi mysticism to the potent brew. Even without overt lyrical exhortations, the largely instrumental albums Sanders recorded moving into the 1970s, such as 1971’s “Thembi”, remain templates for spiritual jazz, imbuing expansive grooves with a wide-eyed sense of cosmic wonder – a sound that was further developed by Sanders’ collaborator, pianist Lonnie Liston Smith, throughout the decade.

PHAROAH SANDERS Thembi LP (Verve By Request Series)

Available to purchase from our US store.In the early 1970s, British guitarist John McLaughlin – a devotee of Indian spiritual teacher Sri Chinmoy – adopted the Sanskrit name Mahavishnu and began to direct his energies towards deeply-felt spiritual offerings. His 1971 album, “My Goals Beyond”, features two long tracks (“Peace One” and “Peace Two”) that sit neatly beside Alice Coltrane’s contemporaneous explorations, fusing Indian musical forms with gently undulating, open-ended jazz jams. While the blazing jazz-rock behemoth he went on to form, Mahavishnu Orchestra, sits a little outside the conventional idea of spiritual jazz, his project Shakti, a collaboration with Indian classical musicians including violinist L. Shankar, spawned deeply devotional music. Their 1975 self-titled debut album includes the track “What Need Have I for This–What Need Have I for That–I Am Dancing at the Feet of My Lord–All Is Bliss–All Is Bliss,” which leaves little doubt about McLaughlin’s motivations.

It’s worth mentioning another pioneering musician whose work is not generally considered to be part of the spiritual jazz canon, but who made some of the most intensely searing declarations of spirituality ever recorded: free jazz pioneer and tenor saxophonist Albert Ayler. Titles like “Spiritual Unity”, “Spirits Rejoice” and “Holy Spirit” bear witness to the apocalyptic spiritual vision that underpinned his fiercely explosive music.

In fact, since the innovations of Ayler and John Coltrane, much free jazz has remained deeply infused with a burning sense of all-embracing spirituality. Saxophonist David S. Ware – a longtime practitioner of Transcendental Meditation – released albums such as “Great Bliss” (1991) and “Renunciation” (2007) before his death in 2012. Bassist William Parker’s 2007 album “Double Sunrise Over Neptune” is a sprawling, groove-heavy date featuring North and West African instruments and Indian-influenced vocals by Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay, which can easily be filed next to McLaughlin’s and Alice Coltrane’s work. Today, young tenor saxophonist Zoh Amba continues the tradition: a committed practitioner of the Hindu Advaita Vedanta tradition, her scorching, post-Ayler sound (heard on albums such as 2025’s “Sun”) resounds with intense longing – a musical quest she describes as “searching, discovering the Creator.”

Spiritual Jazz Today

In the 21st century, other artists continue to probe and investigate the legacy of spiritual jazz. For some, that means going right back to the source. Over the last 15 years or so, British tenor saxophonist Nat Birchall has – with albums like 2022’s “Spiritual Progressions” – built a reputation for creating deep, modal jazz that plugs directly into the sound and sincerity of mid-1960s John Coltrane. It’s a vibe also explored with wild energy by young US saxophonist Isaiah Collier on his expansive 2021 date “Cosmic Transitions”.

For others, the sounds developed by Alice Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders retain a magnetic attraction. British trumpeter Matthew Halsall – another lifelong practitioner of Transcendental Meditation – has patiently mined the treasures of classic spiritual jazz, evidenced most explicitly on his 2015 single, recorded with the Gondwana Orchestra, a note-perfect and deeply reverent cover version of Alice Coltrane’s “Journey in Satchidananda.” Meanwhile, Halsall’s Manchester-based Gondwana Records label provides a home for other British artists drawn to spiritual jazz. Saxophonist/flautist Chip Wickham’s 2025 joint “The Eternal Now” tips its beanie to Thembi-era Pharoah Sanders, while the Leeds-based Ancient Infinity Orchestra’s 2025 date “It’s Always About Love” has the 15-piece ensemble making a joyful noise awash with harp, twin double basses, strings, reeds and sundry percussion.

Even the sound of McLaughlin’s Shakti gets a 21st century make-over courtesy of London/Lahore-based outfit, Jaubi, which flings together young British jazz musicians and South Asian classical musicians playing traditional instruments such as sarangi and tabla. Their 2024 album, “A Sound Heart” – its title inspired by a verse from the Holy Qu’ran – is a transporting fusion of streetwise electric jazz and oceanic, meditative moods, including a version of the classical raga Bairagi Todi.

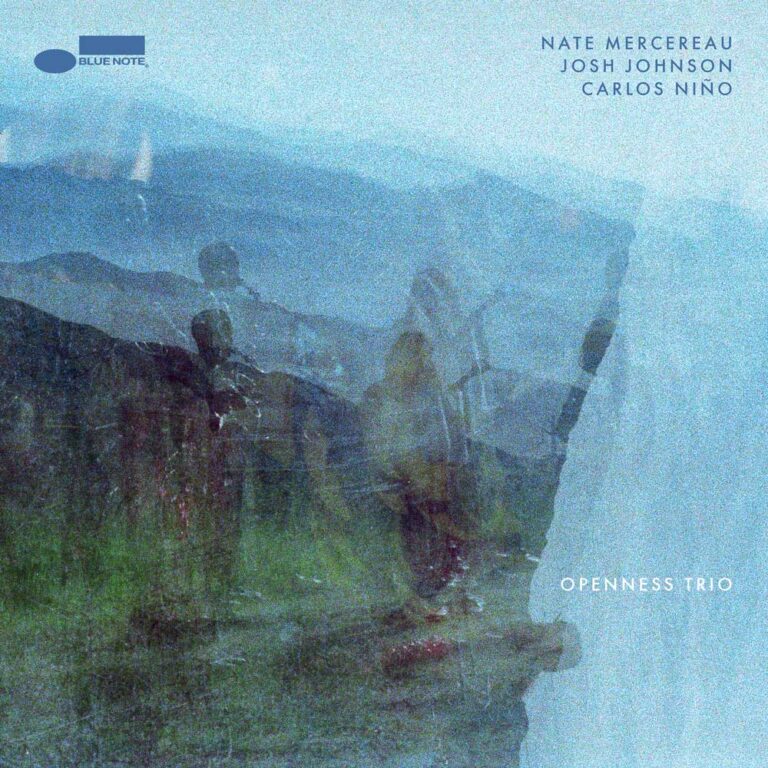

And the genre expands still. British saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings’ work with South African musicians – heard on 2016’s “Wisdom of the Elders” by Shabaka and the Ancestors – presents deep jazz with tough bass grooves and African elements, while his more recent move to concentrate on playing numerous flutes such as the Japanese shakuhachi, on albums like 2023’s “Afrikan Culture”, has opened up a delicate pan-global sound that touches on the warm, spiritually omnivorous impulses of New Age music. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, LA-based percussionist and producer, Carlos Niño, mines the possibilities of combining the New Age vibe with ambient soundscapes and electroacoustic improvisation on albums like the 2025 Blue Note date “Openness Trio”, recorded with guitarist Nate Mercereau and saxophonist Josh Johnson.

The search continues.

Nate Mercereau, Josh Johnson, Carlos Niño / Openness Trio

Available to purchase from our US store.Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of books on German free jazz legend Peter Brötzmann and Turkish psychedelic music.