Our experts have decided: whether brand new recordings or lovingly remastered, reissued and rediscovered treasures – these are our 14 jazz albums of the year. Go directly to each write-up by clicking on the covers below or scroll down to read them all via the drop-down menu.

READ THE REVIEWS

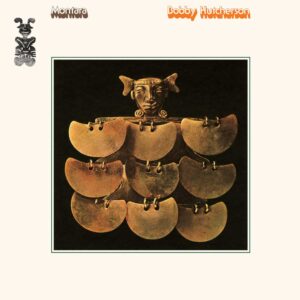

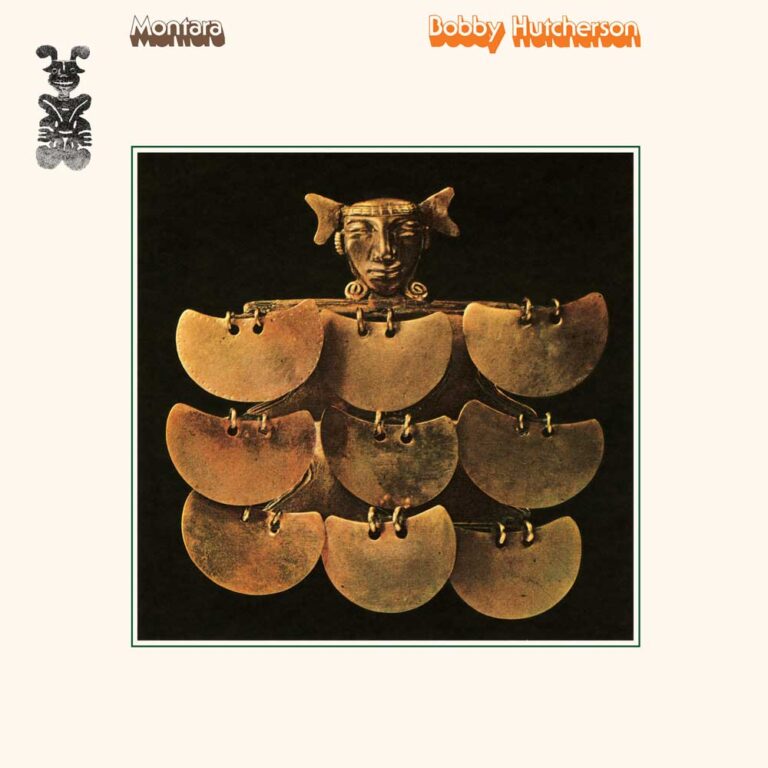

This may not seem like your typical choice, especially since it was originally released over five decades ago.

Album reissues have seen an exponential resurgence since the start of the pandemic. Overall, these past five years have been a period of reflection for perhaps the entire world – a time to take stock of our own lives and of life in general. And while the output of creativity seems boundless today, and across many disciplines, there has arguably been very little that best captures the disillusionment and despair, as well as the lasting hope for the future.

A first-call vibraphonist, Hutcherson’s oeuvre at Blue Note ranks only behind Horace Silver’s, with album releases spanning from 1963 to 1977. As a sideman, he appears on recordings like Jackie McLean’s “One Step Beyond” (his first Blue Note session), Grant Green’s “Idle Moments”, and Eric Dolphy’s seminal work, “Out To Lunch!”. While his idol, the great Milt Jackson, was known for his subtle vibrato and human-like tone, Hutcherson had a pulsating rhythmic drive that was equally melodic and harmonic. His innovative sound rightfully positioned him among the vanguard of post-bop musicians of that era.

Hutcherson worked as a part-time taxi driver before turning to music full-time. While those early hustling days were long gone, the pervasive racism nonetheless persisted. In 1967, he lost his cabaret card (a requisite for performers at NYC clubs) for marijuana possession while in Central Park with his long-time drummer, Joe Chambers. Not long after, in that same year, the cabaret card system was abolished.

By 1975, Hutcherson was just 34 and already an established artist. In those eight years, he would return to his native California, reunite with his collaborator, tenor saxophonist Harold Land, who honed his post-bop style in Max Roach and Clifford Brown’s band, and embark on a whole new sound, fusing jazz with funk and soul.

Between the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War, any one of these feats alone would have been remarkable. Perhaps it wasn’t even a conscious choice to forge ahead. Jazz artists, much like the rest of the world, were at the very least trying to make sense out of the utter confusion and despair that surrounded them. It is that resiliency and determination to forge ahead that you hear in many of the more progressive jazz releases, which speak volumes and resonate with more listeners today.

“Montara” is no exception. Sampled and covered extensively, Hutcherson would enlist a veritable who’s who of artists to capture his newfound direction, especially on the title track: Larry Nash on Fender Rhodes, Ernie Watts on tenor saxophone and flute, percussion from Johnny Paloma, Rudy Calzado, Bobby Matos and Victor Pantoja, Dave Troncoso on bass, Eddie Cano on piano, and Oscar Brashear and Blue Mitchell rounding it out on trumpet.

Named for the small coastal town where Hutcherson settled, “Montara” is equally meditative and infectious, rendering a quixotic escape from the mundanity of ordinary life. Hutcherson’s arrangement leaves ample room for an endless and hypnotic samba groove. Evocative of Bobby Humphrey’s “Harlem River Drive” and The Blackbyrds’ “Rock Creek Park,” “Montara” captures not only the spirit of the times, but the essence of the place itself.

Shannon J. Effinger (Shannon Ali) has been a freelance arts journalist for over a decade. Her writing on all things music regularly appears in The New York Times, Washington Post, Pitchfork, Downbeat, and NPR Music. She lives and works in New York City.

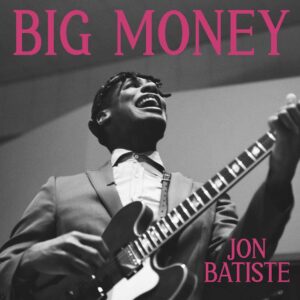

Jon Batiste exhorts on the title track “Big Money”: “You can buy a house, but you can’t buy a home!” This dark but joyful album is the one I have turned to most during this politically troubling year. To me, it feels like an album that documents the deep blues of our times.

Caribbean critic Stuart Hall once commented that “the blues takes you to a dark place, but it doesn’t leave you there”. “Big Money” is like this, we hear the abyss, but it does not drag us into it. Baptiste asks, “What is the truth serum that we don’t want to take? What are we dealing with, and what do we run away from?”

The corrosive power of money and greed is Batiste’s first target. As the descendant of slaves whose humanity was reduced to commercial chattel, Batiste offers a warning against conflating culture with property. In the promotional film made for the album, he comments: “That this is music from an African-American lineage… something that is not for sale and never should be.”

Batiste’s blues is an injunction to live despite the political state of things, from the environmental destruction alluded to in the beautiful track “Petrichor”, to the corruption of truth in the era of tyrants and state violence.

Another central theme in the album is individualism and loneliness. Amongst the eight original songs is an arresting cover of Doc Pomus’s standard “Lonely Avenue” featuring Randy Newman. A languid protest against what I would call the individualisation of everything, including both our successes and failures. You can be surrounded by people but be alone, hyperconnected but also in utter isolation. Batiste’s vision of collective “social music” offers an antidote to what Noreena Hertz calls the century of loneliness. The fact that the music is recorded by the musicians playing together live in the studio enhances this message.

What I love about this album is that it is like a jazz and blues jubilee, a summoning of ancestors to make something new and vital. You can hear them gathering in the album’s sound picture from Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk to Howlin’ Wolf, Professor Longhair. There is also a reference to reggae in the final track, “Angels,” reminiscent of Toots and the Maytals featuring producer Dion “No I.D.” Wilson, nicknamed the Godfather of Chicago hip-hop. Wilson collaborated closely with Batiste throughout the five years it took to make the album.

As Batiste says, the music offers “a gateway for people to have a real understanding of American identity.” It is euphoric protest music that grooves and dances, and insists on a more inclusive sense of American life. He appeals to us to face our times without fear.

“We all inherit a lot of fear, but truth drives out fear and replaces it with an urgent, blazingly fearless love. Don’t let fear break you down… No matter how dark it gets, we can win.” The album is a powerful injunction to be braver and truer as we anticipate what is before us in the year ahead.

Les Back is a sociologist at the University of Glasgow. He has authored books on music, racism, football and culture, and is a guitarist.

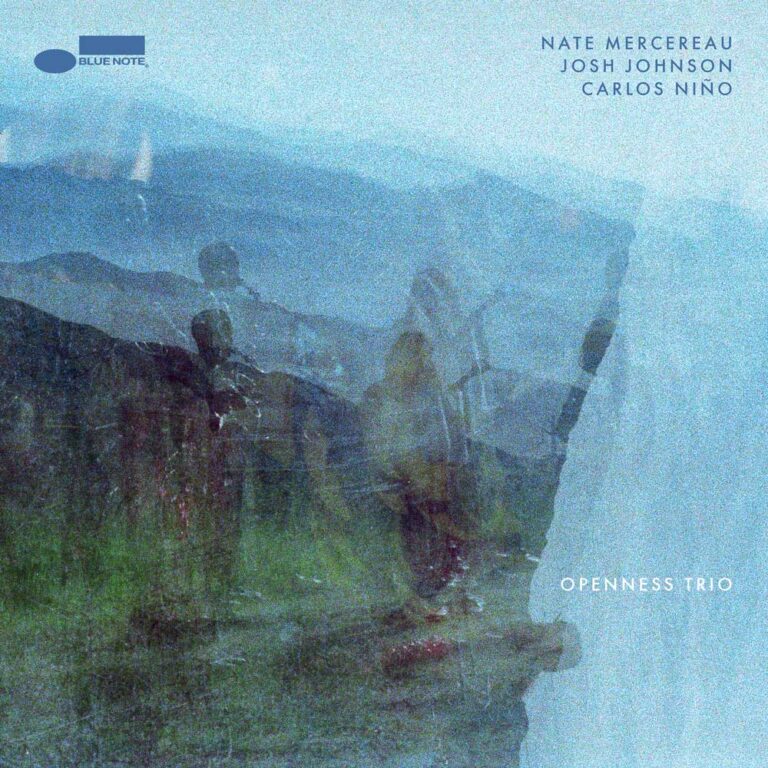

Nate Mercereau, Josh Johnson, Carlos Niño / Openness Trio

Available to purchase from our US store.In Timothy Snyder’s pocket-sized book “On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century”, one suggestion reads: “Make eye contact…and understand whom you should and should not trust…you will want to know the psychological landscape of your daily life.”

On its placid surface, the new age spiritual jazz drifts that Californians Nate Mercereau, Josh Johnson, and Carlos Niño render on Openness Trio might not scan as a means to resisting the malignant forces that otherwise dominated the 2025 news cycle, but something to just chill out to.

But that couldn’t be further from the reality. Like mistakenly perceiving a binary in fiery free jazz and the more mellow spiritual jazz of the 1960s, these two sounds are in fact one expression. That music then and the jazz of now retains that sense of urgent freedom, of connection and belief in others that is vital to remaining together through the turbulence of these times.

“Trust music” is literally how Niño and Mercereau described their music in a recent interview with JazzTimes. “That’s a big one because we’re showing how we care to be with each other…We’re sonically reporting from the inner depths.” Great depths and dizzying heights are both unlocked on the five extended sonic meditations that comprise Openness Trio. Johnson’s enigmatic saxophone, Mercereau’s mercurial fretwork, and Ninõ’s energy waves of percussion create something greater than their individual parts.

There’s a true sense of freedom to be found within this music. Pieces were recorded in the paradisiacal landscape of Ojai, California, in a living room setting in Elysian Park, under a pepper tree in Topanga Canyon, and you can feel how those magical landscapes seeped into the music itself. It’s right there in the opening number “Hawk Dreams,” wherein all three players seem to be a mile up in the clouds, drifting yet highly alert.

While the three have performed in numerous permutations out on the West Coast over the years (and across a number of International Anthem releases, not to mention Niño and Mercereau being in André 3000’s New Sun band), this album marks their Blue Note debut. Openness Trio conveys that tactile sense of a previously underground sound rising to the surface of the mainstream. Which is how all musical revolutions arise. As one song title puts it: “Anything is possible.”

Andy Beta is the author of the forthcoming book, “Cosmic Music: The Life, Art, and Transcendence of Alice Coltrane”. He is based in New York City.

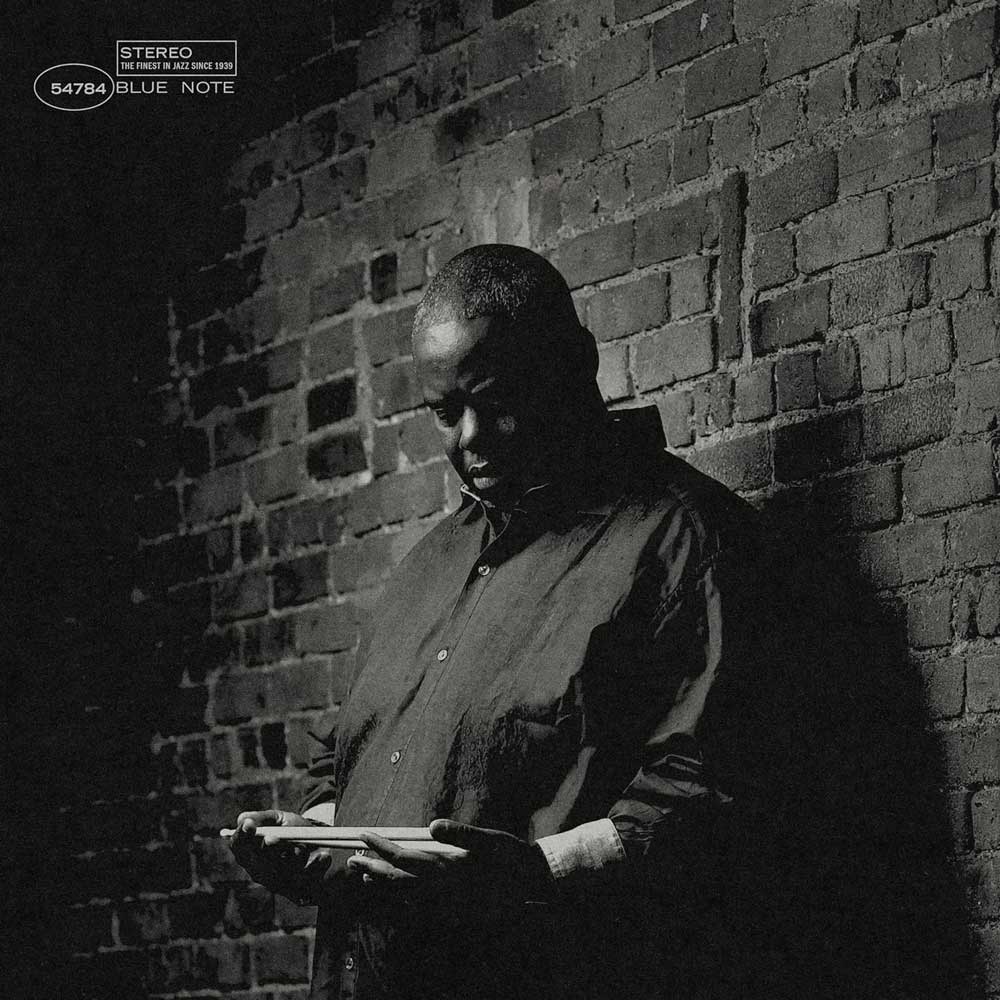

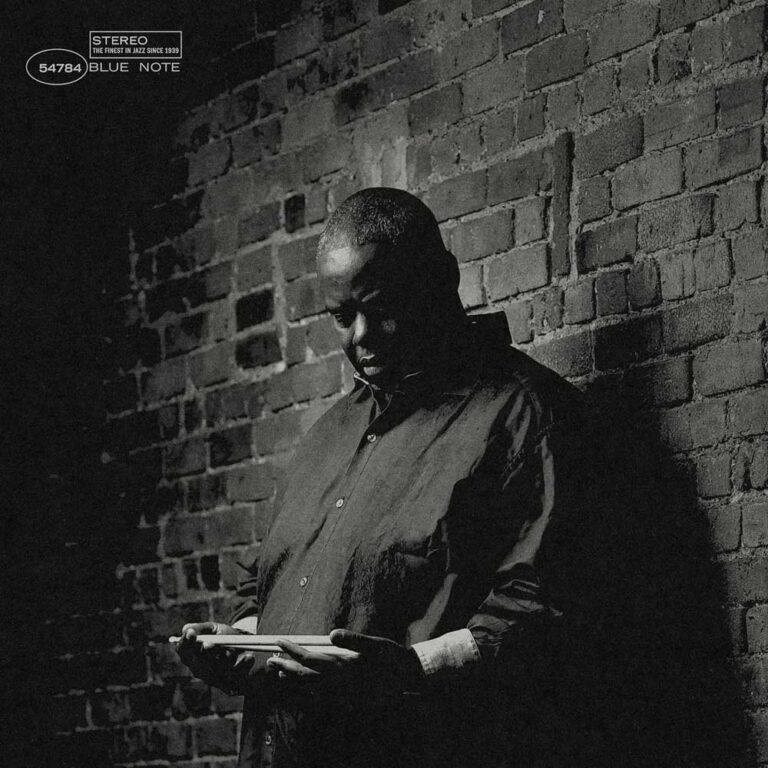

There’s a hallowed tradition of conscious music in African-American culture, and of artists working within the jazz idiom in particular, creating powerful, socially engaged and socially impactful music. This music is still needed in our time, perhaps more than ever. Drummer-composer Johnathan Blake follows in the tradition with great reverence, skill and creative expression on his third Blue Note album, ”My Life Matters”.

Among the African-American jazz artists who pioneered the use of music as a form of social commentary and activism, particularly in response to racism, inequality, and calls for freedom and justice, were Charles Mingus, who addressed school segregation (“Fables of Faubus”) and other forms of racial injustice and hypocrisy in America; John Coltrane, whose haunting “Alabama” and “A Love Supreme” reflect a spiritual and moral striving for unity and higher consciousness; Oscar Peterson, composer of “Hymn to Freedom,” which became a Civil Rights anthem; Max Roach (“We Insist! Freedom Now Suite”); vocalists Abbey Lincoln and Nina Simone, whose voices expressed both the pain and force of the struggle for Black freedom. “Those musicians set the bar very high for us to follow,” muses Blake. “If we’re not following their lead, then we are doing them a disservice.”

It is within this tradition that Blake operates, responding to the realities he encountered as he composed. “Right around that time when I was writing this music, it seemed like every other day I was watching or listening to the news, and it was another person of color – another Black and Brown person – being taken away from us at the hands of people that were supposed to serve and protect us,” recalls Blake. “I didn’t want to become numb to the things that were unfolding in front of me. I wanted to speak up through my music.”

Co-produced by celebrated bassist and labelmate Derrick Hodge, the album features the potent core quintet of pianist Fabian Almazan, vibraphonist Jalen Baker, bassist Dezron Douglas and saxophonist Dayna Stephens, with special guests DJ Jahi Sundance and vocalist Bilal. The music was composed for the Fellowship program of The Jazz Gallery, a New York performance venue, back in 2017. Blake had already been working as a professional musician for over two decades, collaborating with some of the most prominent artists in the jazz world: Pharaoh Sanders, Kenny Barron, Maria Schneider, Tom Harrell, Ravi Coltrane, Donny McCaslin and others. But he had not yet made his mark as a composer. This commission offered the opportunity to share his artistry.

The album, comprised of 14 tracks, weaves six expansive compositions and eight interludes featuring solo / duo expressions. The opening “Broken Drum Circle for the Forsaken” sets the tone, showcasing Blake’s compelling playing from the outset, his urgency enhanced by DJ Jahi Sundance’s turntables and samples. The following “Last Breath” is a haunting tribute to Eric Garner, an African-American man who died after being placed in an illegal chokehold by an NYPD officer in 2014; his dying words – “I can’t breathe” – alluded to in the song title, became a rallying cry for Black lives. The track features Baker’s airy vibes, Stephens soaring on EWI, and Almazan’s propulsive playing, matching Blake’s intensity. Other spacious tracks (“My Life Matters,” “Can Tomorrow Be Brighter?”) reveal more of Blake’s creative talents as a composer; “Requiem for Dreams Shattered” offers powerful piano/electronics and soprano sax solos, Bilal enhancing the tune’s emotional charge. The tender, mournful “We’ll Never Know (They Didn’t Even Get to Try)” features Blake’s son Johna on an electric bass solo. Equally powerful are the brief interludes; on “I Still Have a Dream,” Douglas’ pizzicato accompanies daughter Muna Blake, reciting a poem penned by her mother, Rio Sakairi. “Can You Hear Me?” is an aching roar, Blake solo on drums and cymbals.

“When my sisters and I were growing up, my folks used to always say that if you see injustice happening and you do nothing, you are just as much the problem,” shares Blake. Bridging the deeply personal and the universal, navigating through time, tragedy and hope, this music is his contribution to an important tradition of social engagement through music, reminding us of what we share as human beings on this planet, and also of the fact that there are still many whose fundamental aspirations are mired by the color of their skin.

Sharonne Cohen is a Montreal-based writer and editor. Passionate about arts, culture and the creative imagination, she has been a music journalist since 2001, contributing to publications including DownBeat, JazzTimes, Okayplayer, VICE/Noisey, Afropop Worldwide, The Revivalist, and La Scena Musicale. Her photographs often accompany her writing.

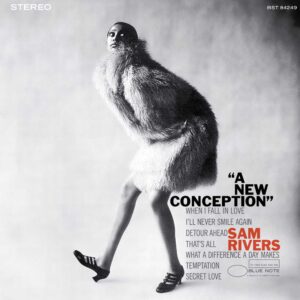

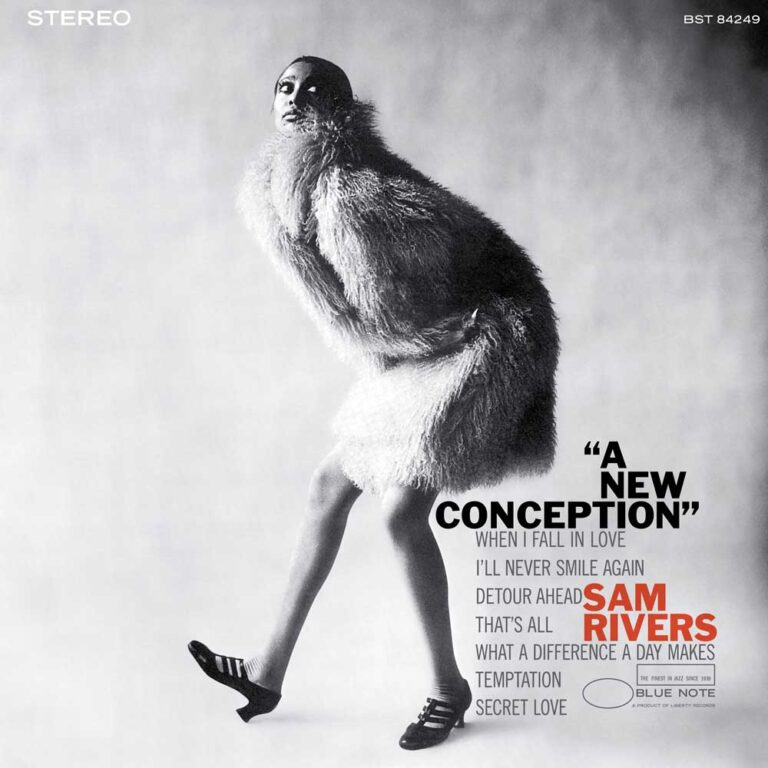

Twenty years ago, I’d only ever seen “A New Conception” on the back wall of the record store, complete with an eye-watering price tag. Even though it was reissued around ten years ago (a couple of years after Rivers passed away in 2011), this album has remained somewhat under the radar still, so I’m very happy to see it getting another new lease of life this year.

With “A New Conception” Rivers took a diversion from his preceding two albums that were more in the then-modern free jazz vein and turned his attention to some of his favourite standards. With that Rivers found this sweet spot, disassembling jazz classics into trail-blazing statements of intent, mutations of their original selves. Rivers and his band apply his “inside-outside” approach to turn these familiar standards into wholly new creations, while still sticking to the chord progressions.

Interestingly, Rivers saw keeping to the original chord structures as liberating. “If I were to stay only within free form,” said Rivers in the liner note, “that would be as constricting as if I were to play only in traditional ways. Furthermore, when I do play standards, I respect the songs as they are. In this album for example, I stayed with the regular changes on every tune. It’s very easy to come up with substitute chords, but it seems to me that it’s difficult for most musicians to play the regular changes and still sound fresh.”

At the time of this album’s release, ‘fresh’ often meant playing in a hair-raising “on-the-edge-of-the-chair” style – a sound Rivers was well-known for. But with “A New Conception”, Rivers proves that creativity can thrive precisely because of restrictions, or in this case, chord changes – and I guess that’s an addendum to the old adage, “necessity is the mother of invention”. Rivers paid homage to the great composers and forebears in the most respectful way he knew, by stamping his unique voice on jazz’s foundational structures. Many think of Rivers as mainly playing free jazz, but his approach was of course steeped in bebop and standards, and the version of “Detour Ahead” included here is a nod to the time he played with Billie Holiday.

For me “A New Conception” is packed with transformative power in the same way as, say, a cubist portrait. While it’s not as explosive as other avant-garde jazz albums of the time, or even Rivers’ own albums like “Fuschia Swing Song” and “Contours”, “A New Conception” is all the more striking precisely because it dances with the formative structures of the standard. The sound is both classic and progressive at the same time, and that’s what gives it a certain timeless quality. It’s like the jazz version of helping an old lady across a busy street – there’s an endearing, respectful quality while at the same time reassuring, as if to say: “Don’t worry. Progress is nothing to be afraid of!”

Max Cole is a writer and music enthusiast based in Düsseldorf, who has written for record labels and magazines such as Straight No Chaser, Kindred Spirits, Rush Hour, South of North, International Feel and the Red Bull Music Academy.

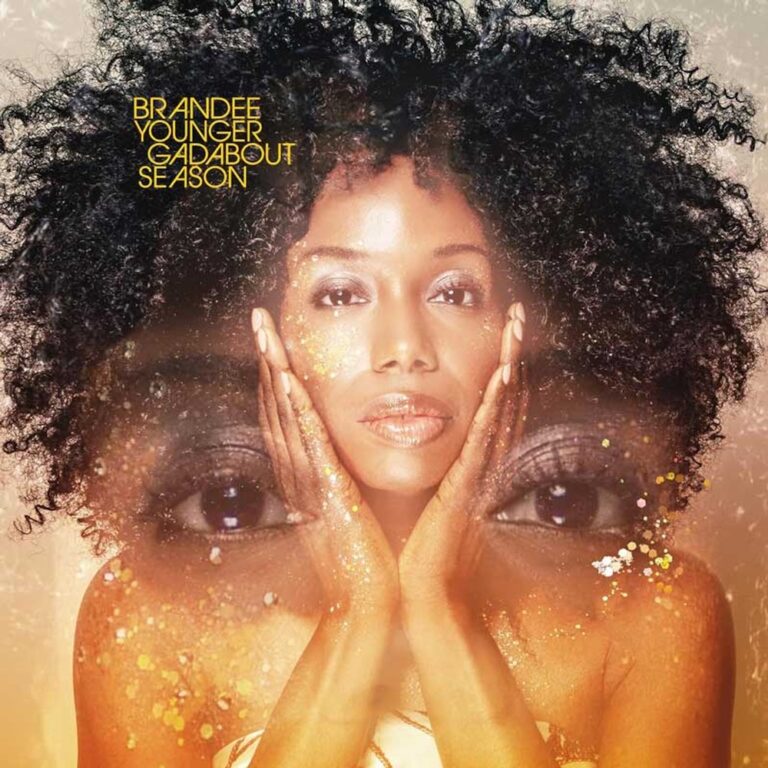

It’s not just that the harp used on “Gadabout Season” is the same Lyon and Healy Style II instrument, hand-gilded with gold, that once belonged to Alice Coltrane. But as you sit, contemplating, after taking an all-original journey signposted by reflection and fire and heart, it ties things up with a bow.

John Coltrane gifted this harp to his wife, who posed with it for the cover of her 1969 debut “A Monastic Trio”. Entrusting the restored treasure to the custodianship of Brandee Younger, the Grammy-nominated musician, composer, bandleader and educator, is a measure of how damn good she is.

Younger’s previous recordings, 2021’s “Somewhere Different” and 2023’s “Brand New Life”, positioned her out as an innovator bent on pushing the harp deeper into soul, hip-hop, R&B and indeed, spiritual jazz territory. The industry took note: the Grammy nod was for Best Composition for “Beautiful is Black” (she was the first black female solo artist ever nominated in the category). Younger collaborated with Beyoncé, Lauryn Hill and the late Pharaoh Sanders.

As much as I loved Younger’s earlier work, “Gadabout Season” got the repeated listens. Titled for the restless wanderer, the gadabout who finds joy and healing in movement, the album was born in the aftermath of personal hardship during a creative retreat in upstate New York. There, with bassist/producer Rashaan Carter and drummer Allan Mednard, Younger traced a narrative arc from loss to acceptance to renewal. Then they returned to Harlem and re-recorded it – this time with a top-tier selection of guests – in Younger’s apartment.

A sort of extended take on Kübler-Ross’s stages of grief (“A year of my life, told in ten tracks,” Younger has said), each tune has a distinct identity. “Reckoning”, the opener, finds tranquil harp flurries blending with hypnotic electronic textures. “End Means”, a declaration of closure, finds Makaya McCraven weaving drum patterns as Younger/Coltrane’s harp dialogues with maverick Shabaka Hutchings’ flute. The title track, with McCraven on percussion, Shabaka on clarinet and Blue Note signing Joel Ross on silvery vibraphone, is imbued with playful flashes of relief.

While “Breaking Point” is riven with fierce hip-hop beats and chaotic harp improvisations, it flows into the serene “Reflection Eternal” and onto “New Pinnacle” before finding stillness in “Surrender”, a beautiful, boisterous tune that takes its cue from Benjamin Britten’s “A Ceremony of Carols” and features pianist Courtney Bryant, flipping the script from 20th century cathedral to 21st century Black church. Younger grew up singing in choir: “The Black church is loud. It has gospel!”

“BBL” has a smouldering, confrontational groove. Featuring the ethereal vocals of the L.A.-based singer/songwriter Niia, “Unswept Corners” has an ambience aimed at healing. “Discernment”, the closer, is given further depth by the dub-tinted harmonics of saxophonist Josh Johnson.

“Gadabout Season” continues Younger’s mission to showcase the harp’s versatility. Centred, agile, expressive, the ease with which she moves between worlds, from the sacred and mythic to the streetwise and modern, warrants repeat listening – and does Coltrane’s gilded harp proud.

Jane Cornwell is an Australian-born, London-based writer on arts, travel and music for publications and platforms in the UK and Australia, including Songlines and Jazzwise. She’s the former jazz critic of the London Evening Standard.

For a number of years, Baltimore-born trumpeter Brandon Woody has been making waves in his home city and beyond. His fiery potential was clear to anyone who crossed his path, from horn player and legend of his local scene Theljon Allen to the wildly influential Robert Glasper.

With “For The Love Of It All”, Woody built on years of study, gigging and composition to deliver what is for me the album of 2025 – comprised of six perfectly considered cuts that pack a huge emotional punch.

Channelling hard-bop heroes of the Blue Note back catalogue such as Lee Morgan and Freddie Hubbard, it seemed only fitting that Woody should join the prestigious label too. His music references the sonic intensity of the aforementioned hard bop greats, while existing firmly in the lane of contemporary post-bop.

By the time Woody came to record “For The Love Of It All”, he and his backing band Upendo (the Swahili word for love), were already a well-oiled machine that had road tested much of the material that would make up the album.

Across the set, the listener is treated to stellar performances from each of the four core musicians. Alongside Woody’s dextrous trumpet work, Troy Long provides thoughtful and expressive piano accompaniment, Michael Saunders delivers fluid basslines while Quincy Philips completes the quartet with his detailed but powerful drum work.

On an album full of standout moments, the opener “Never Gonna Run Away” – an ode to Woody’s love of Baltimore – sees the band passionately firing on all cylinders as the guest vocals of Imani-Grace perfectly compliment the warm but potent lead trumpet lines.

Throughout the record, from the richly melodic and deeply emotional “Perseverance” to album closer and the band’s de-facto theme “Real Love Part 1”, Woody demonstrates a maturity as a composer and player that belies his years.

As I’ve come back to “For The Love Of It All” throughout the year, it has only grown on me, with new details and elements of the interplay between the musicians popping out freshly with repeat listens.

Ahead of the album’s release, I was lucky enough to interview Woody for Everything Jazz. I knew of him as an upcoming player and had heard a couple of cuts, but I wasn’t prepared for how much the album would blow me away ahead of our conversation.

My interview with him has been one of my most memorable this year. Zoom calls can make it harder to build up a rapport with an interviewee, but there was no such issue with Woody. His passion for the music, his band and the inspirations that have got him to where he is, shone through everything he said.

It was a wide-ranging conversation that touched on struggle, his upbringing, the power of music and his hopes for the future. Of the album, he told me that “it feels like Black struggle and Black success. And it feels like my ancestors.”

With “For The Love Of It All”, Woody has released one of the most fully realised jazz debuts I’ve heard in years. It’s a record that knows its history but firmly faces the future. I had high expectations going into it, but they were thoroughly exceeded. After this triumphant debut, the future looks bright for Brandon Woody.

Andrew Taylor-Dawson is an Essex based writer and marketer. His music writing has been featured in UK Jazz News, The Quietus and Songlines. Outside music, he has written for The Ecologist, Byline Times and more.

There’s an abundance of guitar-wiedling singer-songwriters, so what does it take to rise to the top? Don Was would know. Maya Delilah’s debut album came off the back of a call with the Blue Note president, who saw something exceptional in her on TikTok.

“The Long Way Round” is rich with ideas and marks a confident arrival from a promising artist. Inviting and nostalgic in tone, the album diarises the life of a young woman born in the 2000s who is navigating relationships, her place in the world and how to orientate a sense of self; a deeply relatable record for young ears during turbulent and fast-changing times.

With her guitar as a springboard, Delilah draws upon various corners of her instrument’s roots; jazz, folk, soul, country, funk and Western-tinted Americana all have their subtle moments. Alongside these elements, the North Londoner’s songwriting and voice – warm, relatively unprojected and deeply contemporary in style – unite her characteristic style.

Delilah’s songs are neat packages, each one clear in theme with memorable hooks. Some are made moreish with creative harmonies; check out the interplay between her guitar and Cory Henry’s organ on “Jeffrey”. Her lyricism is another pull. On “Maya, Maya, Maya” she sings, “Flicking through a magazine, seeing all the people that I will never be, I bet life was good before TV, where people said good morning and wrote in diaries”, evoking a mysterious yet relatable sense of loss for younger listeners. On “Did I Dream It All” she pulls us into romantic despair; “I see no other way, too late to hesitate, a lion in the cage, and as the days go by, you must be wondering why, my dreams won’t let us die.”

Delilah’s dexterity on the strings shines bright. Two wholesome solos feature on the bookends of the album, showcasing her skills as a guitarist-first and vocalist second. There’s also some groove amongst the gentleness. “Squeeze” drips with a propuslive bass line and a Lenny Kravitz kind of swagger.

Delilah dedicated herself to her instrument for eight hours a day during lockdown, further honing the skills that she’d been developing as the only female electric guitarist in her class at the iconic BRIT School in Croydon, South London. In good company, the school also counts Amy Winehouse, Adele, FKA Twigs and Cat Burns amongst its esteemed alumni. The fact that Delilah learnt to play the guitar predominantly by ear, in an effort to circumnavigate her severe dyslexia, could go some way to explaining her agility across the fretboard and skilled comfort in improvisation.

Inspired by the likes of Derek Trucks, John Mayer and Ella Fitzgerald, Maya Delilah has produced a stellar debut that documents the early days of a rising star. Much like what “Alas, I cannot Swim” was to fellow English singer-songwriter Laura Marling, I expect that “The Long Way Round” is similarly a precursor for even better things to come.

Tina Edwards is a music journalist, DJ and broadcaster. She’s the co-founder of curatorial platforms re:sonate and Queer Jazz, and hosts her own Bandcamp Club called Jazz-ish Jazz Club. She has bylines in Bandcamp Daily, Downbeat, Monocle and more.

A concept album where the concept doesn’t get in the way of beautifully crafted music – which holds a hidden secret.

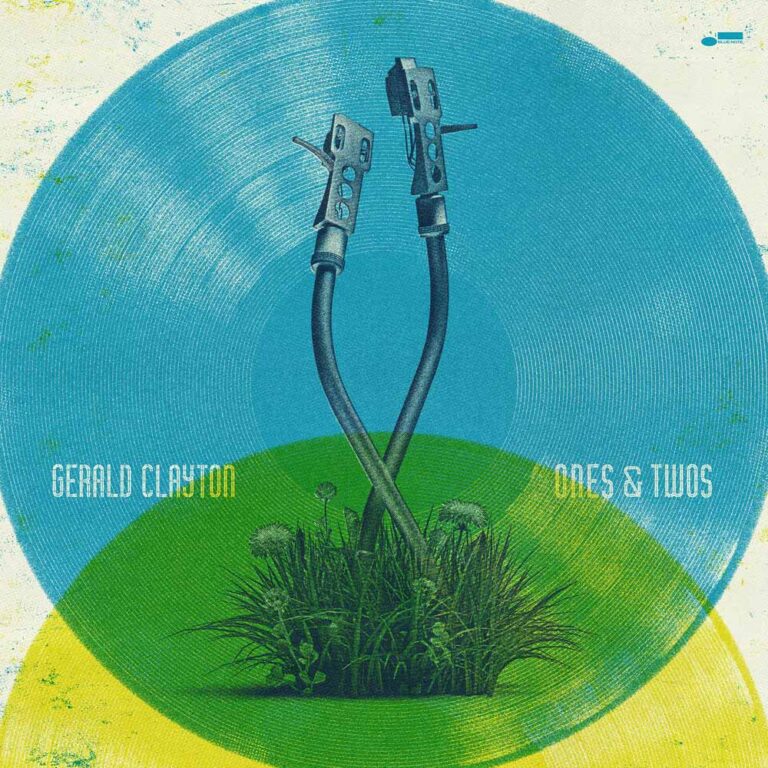

Pianist Gerald Clayton has had a good year and his new record “Ones and Twos” for Blue Note is testament to the pianist’s work ethic. Alongside this new album, he’s a member of new generation supergroup Out Of / Into – who have released two great albums within a year –, is sideman to the likes of John Scofield, and has a tour schedule that must garner the respect of the most seasoned of musical nomads.

So where did he get the headspace to come up with such an intricate and inventive record – or should that be two records?

In homage to the turntablists and DJs who formed the backbone of his teenage listening, Clayton pulls off what plenty before him have failed to do – he’s created a jazz record infused with a hip-hop mindset that is so much more than a concept.

“Ones and Twos” works as a regular album; 14 original tracks of tightly conceived music which range from soulful, to dramatic, to searching. But when both sides are played simultaneously, a whole new vista opens up – each track on side A interlocks perfectly with the side B cuts, delivering another 7 tracks which feel both familiar and new. Much as a DJ can conjure a new musical world using turntables and a mixer, Clayton has created the same effect with a whole band. And it works.

Once you’re in on the trick, it does feel like you’ve just won a bonus prize, but there are philosophical ideas behind the experiment; “the project asks questions,” Clayton says. “Is it possible for two melodies to exist at the same time? Will they inevitably become a melody and a countermelody, with one deferring to the other? Or can two really separate, strong melodies exist and even succeed together?”

For me, the answer is a resounding yes – and the resulting counterpoint feels all the more delightful for being able to be heard in its constituent parts before we hear the full effect.

A huge part of the success of “Ones & Twos” is down to the ensemble, chosen from Clayton’s circle of close collaborators: Out Of / Into bandmates Joel Ross on vibraphone and Kendrick Scott on drums; Elena Pinderhughes on flute (who can turn on a vibrato is so warm and wide it’s like a sonic hug); Marquis Hill on trumpet; and Kassa Overall on production and percussion duties.

The thoughtful arrangements and smart use of the instrumentation signal cinematic chamber jazz. Rolling piano solos emerge from blooming clouds of ensemble work and the distinctive, warm, clean sound of the band make this a record that will work for jazz lovers and newcomers alike. If you want extended solos of pianistic fireworks and grandstanding, you’re barking up the wrong tree.

Perhaps the reason why this creative outlook works so well, where so many other attempts have failed, is down to Clayton & Co’s generation. Now in his early 40s, Clayton came of age in the golden era of hip-hop, soul and R&B – he’s been steeped in the good stuff his whole life. Fellow jazzers like Branford Marsalis and the late Roy Hargrove pioneered a jazz / hip-hop / soul fusion before him, but Clayton’s music feels less like a blending of genres, and more like a new direction in its own right.

Blue Note’s habit of working with great pianists at all stages of their career shows no sign of slowing down – just take a listen to Paul Cornish’s debut “You’re Exaggerating” if you need evidence.

This is a chameleon of a record which shifts its shape depending on the perspective you bring to it. More importantly, perhaps a jazz record can do some of the societal bridge-building that has proved so elusive in much of our public discourse this year. We have a lot to learn from Gerald Clayton.

Freya Hellier is a content editor for Everything Jazz. She has spent many years making programmes about all genres of music for BBC Radio 3, Radio 4 and beyond.

Blake Mills and Pino Palladino are two of the most prolific sidemen working in music today. Bassist Palladino is perhaps best-known for his neo-soul work with D’Angelo, as well as for performances with John Mayer, Adele and The Who. Producer and multi-instrumentalist Mills, meanwhile, has worked with everyone from Bob Dylan to John Legend, Laura Marling and Perfume Genius. Theirs is a freewheeling, malleable sound, seemingly capable of slotting into all manner of genres and combos.

As a duo, Mills and Palladino’s 2021 debut record, “Notes and Attachments”, was a testament to their immense musical flexibility, delivering eight tracks of restless, genre-agnostic instrumentals. On this year’s follow-up, “That Wasn’t A Dream”, the pair double down on their omnivorous creativity, composing woozy instrumental arrangements that might initially play like downtempo background listening but that ultimately seep under the skin and linger thanks to their slippery indefinability.

Opener “Contour” sets the tone, delivering pleasant finger-picked Latin guitar and plaintive bass rhythm over hand percussion before reverb-laden woodwinds susurrate and set the melody off-kilter, destabilising this otherwise tight-knit composition. Ensuing track “Somnabulista” revels in this uneasiness, interjecting synth sound and fractal vocal melody into an otherwise pleasantly lilting arrangement, while “I Laugh In The Mouth Of The Lion” punctuates gently strumming guitar melody with what sounds like a pulsing alarm buried in the mix, adding a sense of unease each time the listener sinks into the groove.

Other tracks like “Taka” start in this disquieting mode, thanks to buzzing stabs of bass and snippets of melody that ring out before the duo ease into a sludgy take on P-Funk, with Palladino showcasing his signature head-nodding sense of bass groove over Mills’ electronically processed woodwind melody, while the Brazilian bossa references of the closing title track equally see the pair locking into a counterpoint-laden arrangement while whispered, keening vocalisations and a drowsy swing feel once again add a sense of difference and unfamiliarity to the track.

Much like the first moments when you wake from sleep and are still in the haze of your dreamworld, “That Wasn’t A Dream” luxuriates in a strange liminality, wafting through musical textures without remaining rooted or anchored in a single movement. It’s an album that constantly shifts beneath your feet as you listen.

The 13-minute album highlight “Heat Sink” is a perfect example of this mode, expertly enlisting featured saxophonist Sam Gendel’s synthesised horn sound to produce a yearning, detuned solo that riffs over Palladino’s steadfast, slowly building bass harmonics. Across the languorous runtime of the track, the trio tell a musical story that meanders like a journeying monologue, conveying impressionistic meaning without words.

In our current era of algorithmic predictability and AI deep-faking, the music made by Palladino and Mills is so enthralling because of its innate strangeness – the sense of imminent collapse or chaos that could only come from the imprint of human creativity. Their arrangements might sometimes be jarring and are certainly unpredictable but they never fail to hold our attention thanks to their distinct singularity of voice – a sound that individually might have previously appeared on other artists’ work but that together could only be the work of Palladino and Mills.

Ammar Kalia is a writer and musician. He is The Guardian’s Global Music Critic and writes for The Observer, Downbeat, Jazzwise and others. His debut novel, “A Person Is A Prayer”, is out now.

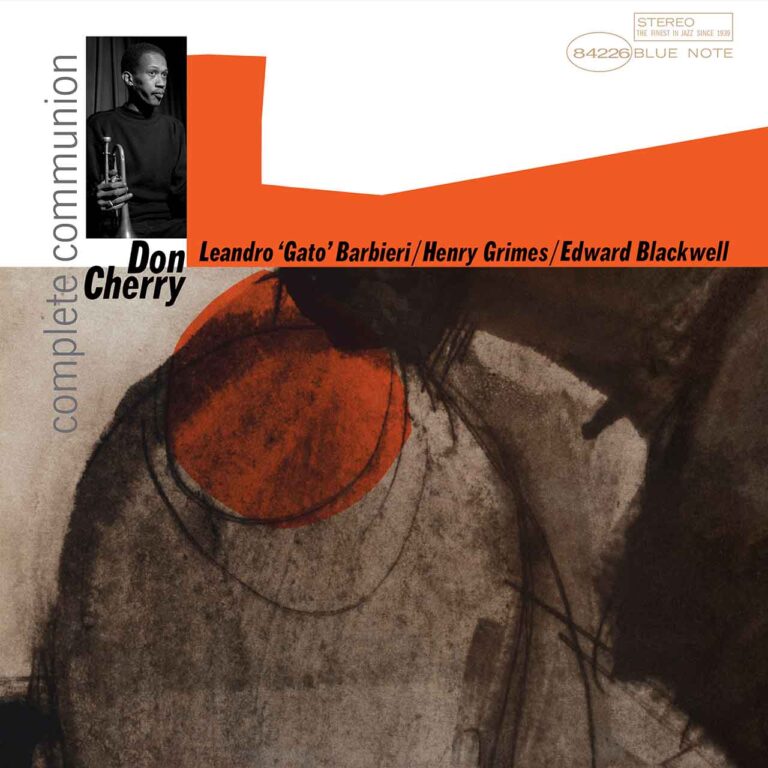

I still remember vividly when and where I heard this first. Madlib had sampled a portion of the A-side for the Quasimoto tune “Microphone Mathematics”; at the time I was constantly seeking out sources that my favorite hip-hop producers had used in their tracks, and often ended up liking the originals even more than the songs that sampled them. The same thing happened to me with “Complete Communion”.

Fast forward to 2025. Whenever I’m skimming through music business news and headlines, I immediately get frustrated. One of the bleakest recent developments in the industry is the completely unjustified hype about generative AI, which will soon have us all drowning in a sea of slop. My immediate reaction is to seek refuge and turn the other way. I ditch my streaming service and start spending an unreasonable amount of money on physical records. Musically, I return to a pre-digital era when skilled human musicians were still recording their ad hoc improvisations directly to tape, without much room for error correction.

My favorite rediscovery of the year is Don Cherry’s revolutionary 1966 slab of free jazz, “Complete Communion”, his first album as a leader for Blue Note, recorded with a stellar group of players, among them a rhythm section that Cherry had played with since his early days in Ornette Coleman’s group (Henry Grimes and Ed Blackwell), and the Argentinian saxophonist Leander “Gato” Barbieri.

The late German jazz writer Ekkehard Jost called this album one of the most important documents of the 1960s avant-garde in his influential book “Free Jazz”. I’m happy that Joe Harley included a remaster in his revered Tone Poet series this year.

In my original piece recounting the backstory of the album, I write that “every one of the four players gets an equal voice. There is no bandleader, only bandleaders. No soloists, all soloists. It’s a spiritual thing, a communal thing.”

What I love most about Cherry’s compositions is that they’re firmly rooted in the bop framework, while allowing the musicians to break out at any given time, in any imaginable way. In terms of moving away from the tonal centre, Cherry and his peers go even a step further than Coltrane’s or Dolphy’s modal jazz innovations; nevertheless I find these suites closer in spirit to Jackie McLean’s and Sonny Rollins’ work of the time than, say, some of Anthony Braxton’s or Cecil Taylor’s post-classical abstractions. They’re still steeped in Black music history.

“Complete Communion” is proof that free jazz can be great listening music – not just in a live setting, but as recorded music too. For me, returning to it in 2025 isn’t about glorifying a better past; it’s about looking backwards to find the right way forward, actually reliving what is to be cherished about human-made live music, and what we’re about to lose in a world where 97% of listeners can’t even discern creative work from AI-generated background fodder. This music reminds us what is currently at stake, and it serves as a gateway to reconnect with everything I love about it.

Stephan Kunze is a writer, book author and a commissioning editor for Everything Jazz. He writes the zensounds newsletter on experimental music and culture.

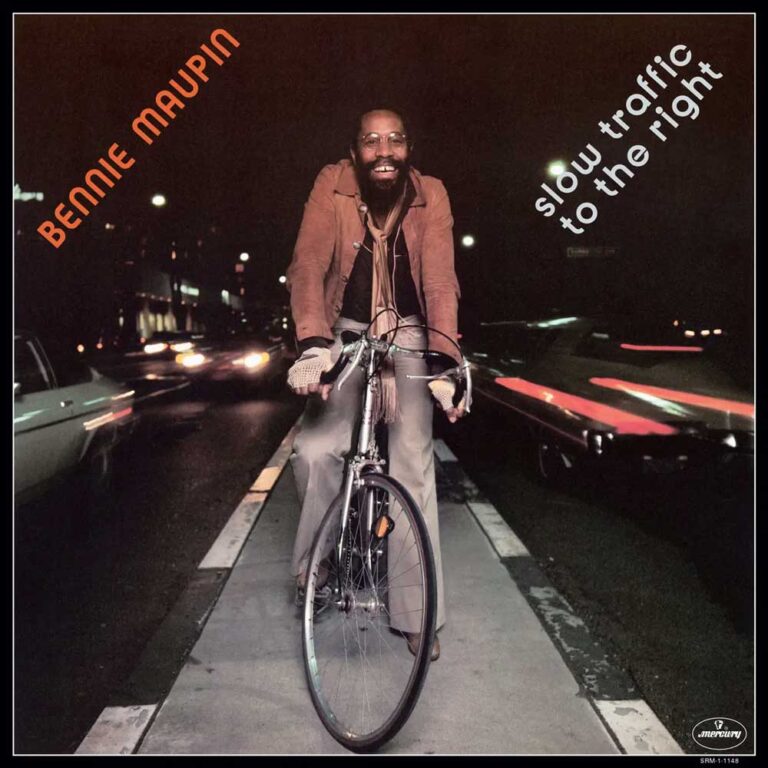

What a treat to see Bennie Maupin’s 1977 album “Slow Traffic To The Right” getting a posh vinyl reissue this year. It’s a key artefact of a time when all kinds of Black Music subgenres were merging: jazz/funk, spiritual jazz, modal jazz, free jazz.

In a way the album also brings to an end a golden era of material by artists like Gil Scott-Heron, Leon Thomas, Gary Bartz, Lonnie Liston Smith and Herbie Hancock, just before machine-made R’n’B and disco really took hold (it’s probably worth noting that the streaming version of Maupin’s follow-up album “Moonscapes” features a really weird disco take on Gerry Rafferty’s “Baker Street”…).

Maupin is of course best-known as the multi-reed player in Herbie’s Head Hunters band, but “Slow Traffic” was only his second solo album. He brought a few key players over from Hancock’s “Secrets” – drummer James Levi, maybe the unsung hero of 1970s groove music, never overpowering but always probing, synthesist/sound designer Dr Patrick Gleeson (who also lent his San Francisco studio Different Fur for the recording) and master bassist Paul Jackson. Just 23 at the time of recording, Patrice Rushen was the “Herbie” of the album, playing superb Fender Rhodes and clavinet.

Opener “It Remains To Be Seen” could have been on “Secrets”, while “Eternal Flame” features a Latin beat and minor-key bass vamp, but the keyboards play in a major key over the top – another Herbie trick. Arranger Onaje Allen Gumbs is key here – check out Marcus Miller’s online tribute to read all about Gumbs’ illustrious career.

“Water Torture” has a serpentine Maupin melody, classic bass vamp in G (with lovely, unexpected drop down to E now and again) played by ex-Mahavishnu Orchestra bassist Ralphe Armstrong and some funky Rushen Rhodes comping. But the strings and chanted vocals hint at something much more menacing.

Even “You Know The Deal” – not written by Maupin – should be standard cop-show funk but comes complete with bizarre touches like the spacey synths, phased bass and heavy electric guitar from Funkadelic’s Blackbyrd McKnight.

“Lament” features some strikingly McCoy Tyner-esque piano playing from Gumbs, who also writes the closing “Quasar”. With its weird 7/8 groove and epic strings, you can imagine Leon Thomas singing on this. Eddie Henderson also arrives to fire off a typically incisive flugelhorn solo.

“Slow Traffic” is a relatively brief album, and Maupin doesn’t feel the need to overpower with long solos, rather letting each player offer something unique on each track. He followed it up with “Moonscapes” – also a fascinating listen, if a little smoother round the edges – but has hitherto pretty much avoided R’n’B-tinged “fusion” during his solo career. And one doubts how commercially successful this period was for Bennie – the era of “Birdland” and Chuck Mangione’s “Feels So Good” was relatively short. So it’s a good time to merge with the “Slow Traffic”.

Matt Phillips is a London-based writer and musician whose work has appeared in Jazzwise, Classic Pop, Record Collector and The Oldie. He’s the author of “John McLaughlin: From Miles & Mahavishnu to the 4th Dimension” and “Level 42: Every Album, Every Song”.

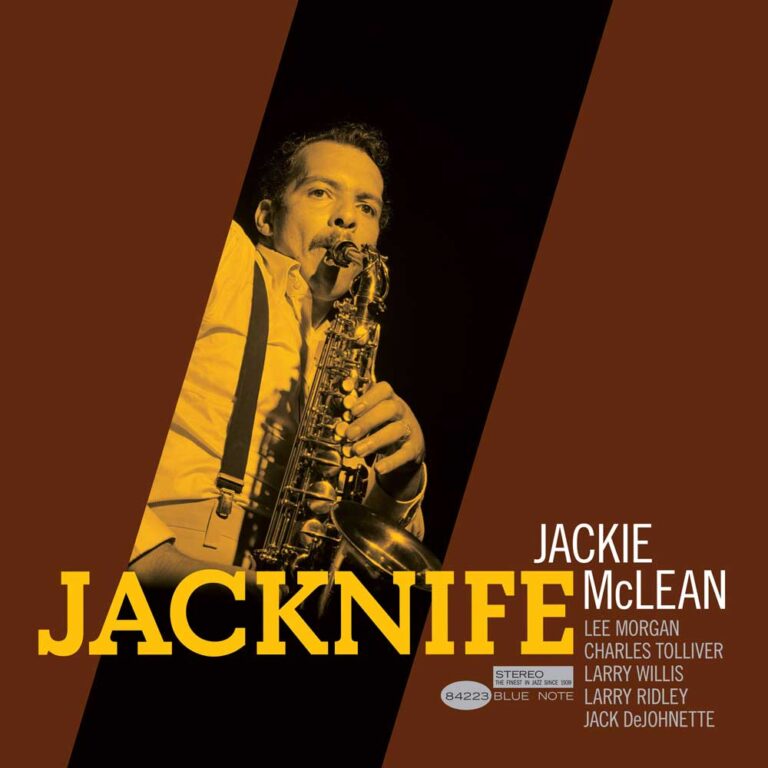

Alto saxophonist Jackie McLean’s extensive discography of recordings made from the mid-1950s to the early 1960s – first for Prestige and then for Blue Note – cements his reputation as one of the key voices of hard bop: tough, deeply swinging, with an unshakable foundation in the blues. But he was a searcher too, with a keen ear for the radical changes jazz was going through during that turbulent period and a desire to let his art evolve and absorb new developments.

1962 was the year this transformative urge first bore fruit, with the release of “Let Freedom Ring” ushering in a fresh sound that, though still firmly grounded in hard bop, incorporated some of the harmonic innovations of Ornette Coleman’s world-shaking conception of free jazz, while also hinting at McLean’s increasing interest in modal jazz. It also saw McLean starting to play with a wider roster of musicians with experience in the avant-garde New Thing – most notably drummer Billy Higgins who had played on Coleman’s groundbreaking first albums in the late 1950s.

Recorded just a few years later in September 1965 (though not released until a decade later), McLean’s “Jacknife” is a blazing example of this twin imperative to honour the tradition while simultaneously making things new.

The band he assembled for the date included a handful of young players just starting to make waves. On drums, and a month shy of his 23rd birthday, was Jack DeJohnette, making his recording debut and still a year away from joining saxophonist Charles Lloyd’s quartet. On trumpet was 23-year-old Charles Tolliver, who had made his debut the previous year on McLean’s “It’s Time!” 22-year-old Larry Willis was at the piano, having recorded for the first time in January that year on McLean’s “Right Now”. Bass duties were held down by 32-year-old Larry Ridley, who had contributed to “Destination… Out!” in 1963. And, providing second trumpet, was Lee Morgan – aged just 27 but already a hugely experienced architect of hard bop who had spent years in Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and who, just a week before the recording of “Jacknife”, had recruited McLean to play on his album, “Cornbread”.

With such young and hungry talent in the band – most of them composers in their own right – it’s no surprise that “Jacknife” is packed with memorable tunes. Kicking it off – and, at 12 and a half minutes, the album’s longest cut – is Tolliver’s “On The Nile.” A stately exercise in modal jazz with a suitably pharaonic theme reminiscent of a Technicolor sword-and-sandal epic, it’s pushed along by DeJohnette’s oddly limping polyrhythms, setting the stage for a McLean solo that bathes in mystery from its very first notes.

DeJohnette’s “Climax” begins with an urgent, staccato rattle like a teletype machine in overdrive, before diving into racing hard bop with McLean utterly at home in a brisk tempo, flying high and bright with his debts to bebop and the blues on full display – and Morgan demonstrating his mastery of the horn with high, tight peals delivered with utmost precision. Morgan’s contribution as a composer, “Soft Blue” – the only track on which both he and Tolliver play – is easy-going soul-jazz with a hint of bossa, hung on an irresistible bass vamp.

The title track, composed by Tolliver, bursts out of the gate with a tangled fanfare and hunkers into another furiously fast hard bop blow-out with McLean swinging hard, boisterous drums and Tolliver blowing taut, insistent lines. Finally, “Blue Fable” – McLean’s only original on the album – is a louche blues crawl with a complex head full of unexpected key changes that nevertheless finds McLean at his most smoky and nocturnal as he sails effortlessly over the changes.

Jacknife is a prime document of the questing sound of mid-1960s Blue Note, conceived by one of the true godfathers of the hard bop milieu it sought to transcend – the one and only Jackie McLean.

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music, a book about German free jazz legend Peter Brötzmann and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

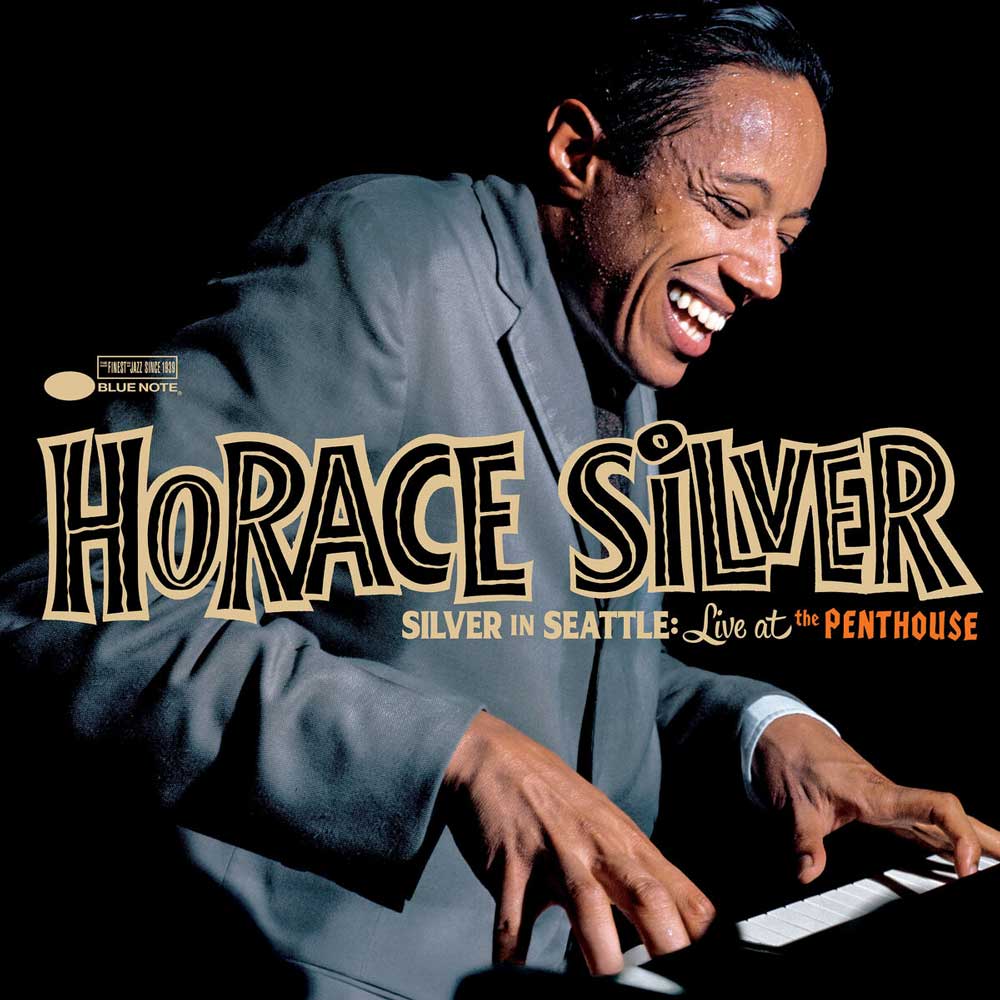

Blue Note engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s aim was to capture the natural warmth, realism, intimacy and in-the-moment presence of live jazz in the studio. So it was somewhat surprising that despite well-known LPs like “The Ornette Coleman Trio: At The Golden Circle, Stockholm” and Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers’ “Meet You At The Corner of the World” there weren’t more live jazz albums released by Blue Note during the golden era.

When I came to write a feature for Everything Jazz on live albums recorded for Blue Note, it left me wondering how some of the famous line-ups would have sounded in a small jazz club when these legendary artists were at the peak of their powers. Thanks to the serious investigative work of Zev Feldman aka The Jazz Detective, some of the gaps are now being filled and the results are every bit as incredible as you might expect.

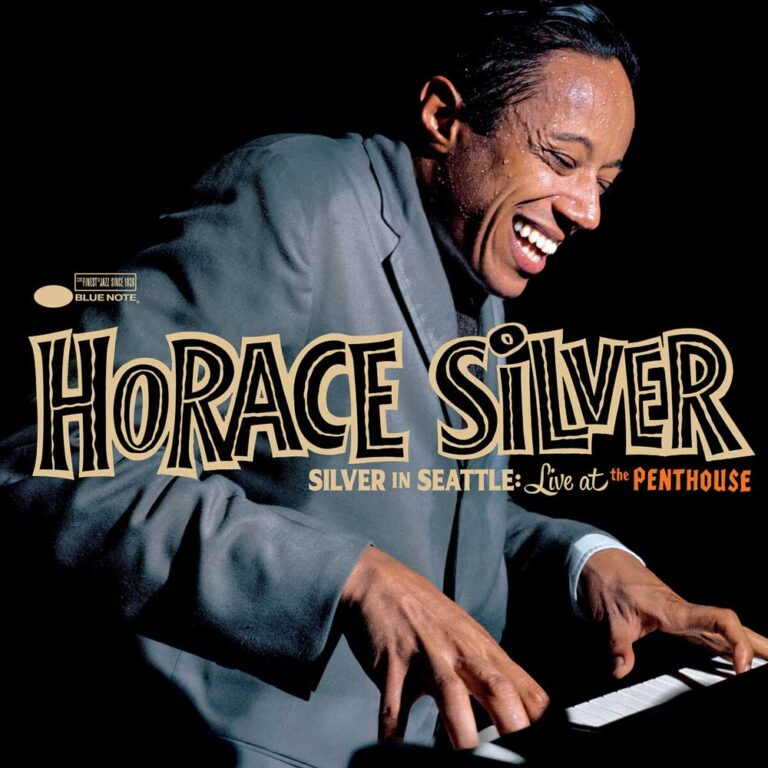

Following Elvin Jones’ “Revival: Live at Pookies Pub” from 1967, Art Blakey’s “First Flight to Tokyo: The Lost 1961 Recordings”, and McCoy Tyner & Joe Henderson’s “Forces of Nature Live at Slugs” from 1966, this year Blue Note released a lost live recording by Horace Silver’s Quintet that caused a storm with label aficionados.

It was in August 1965, a year after the release of his classic Blue Note album “Song For My Father”, that Silver took his Quintet (Woody Shaw on trumpet, Joe Henderson on tenor saxophone, Teddy Smith on bass, and Roger Humphries on drums) to The Penthouse in Seattle, where a concert of John Coltrane’s would also be recorded that year.

Two nights of the run of concerts, from August 12th to 21st, were recorded by radio host and engineer Jim Wilke. His tapes have now been transferred to vinyl for this beautifully presented release, produced by Zev Feldman who first tracked down Wilke back in 2010.

The beads of sweat running down the face of Silver as he hits the keys on the beautiful cover photograph by Francis Wolff suggest the intensity of the pianist’s live performance. Drop the needle on the record and the warm applause of the crowd evokes the atmosphere of that summer night in Seattle as the Quintet powers into the opening number “The Kicker”.

You can only begin to imagine what it was like to be there that night when the opening strains of “Song for My Father” filled the room. Extended from the album track by two minutes, the notable additions on this joyous number are an Eastern modal passage by Henderson. Even more jaw dropping is the epic 18-minute version of “Sayonara Blues”, taken from the 1962 album “The Tokyo Blues”, a big favourite of Gilles Peterson who waxed lyrical about the album on its release.

The album was presented in a majestic booklet with words by Zev Feldman, Bob Blumenthal, Roger Humphries, Silver alumni Randy Brecker and Alvin Queen, pianist Sullivan Fortner, next to photos by Francis Wolff, Burt Goldblatt and Jean-Pierre Leloir with snaps and flyers of The Penthouse. Such loving attention did justice to one of the greatest live jazz records of all time by one of the greatest quintets.

As Blue Note President Don Was writes in the intro of the booklet: “Silver in Seattle provides a missing link in our understanding of Horace Silver’s music.” Essential for any Blue Note or jazz fan. It’s hardly been off my turntable since buying it.

Andy Thomas is a London based writer who has contributed regularly to Straight No Chaser, Wax Poetics, We Jazz, Red Bull Music Academy, and Bandcamp Daily. He has also written liner notes for Strut, Soul Jazz and Brownswood Recordings.