Horace Ward Martin Tavares Silver was an enlightened individual who believed in the healing power of music. His glittering Blue Note solo career is a testament to that philosophy, and the 1965 classic “Song For My Father” is arguably its primary tenet.

Silver is also one of the few jazz pianists who always prioritised horn-led ensembles, perhaps not surprising as he started out on tenor saxophone at school. But, inspired by Bud Powell, he moved over to the keyboard in the late 1940s, quickly picking up work with Stan Getz, Lou Donaldson and Miles Davis, and in an early incarnation of The Jazz Messengers with Art Blakey. But it was his own infectious compositions – premiered at Minton’s Playhouse during 1954 – that really put him on the musical map, fusing bebop, gospel, Latin and R&B styles.

The million-selling “Song For My Father” arguably represented the peak of his career. The album showcased his knack for simple, catchy melodies that were neither trite nor grating – often the hardest to write. Silver was also a meticulous rehearser who insisted that his music was played correctly. And what an ensemble he selected to achieve that – Joe Henderson on tenor sax, fresh from other Blue Note classics like Andrew Hill’s “Black Fire”, Lee Morgan’s “The Sidewinder” and Grant Green’s “Idle Moments”. Trumpeter Carmell Jones came to Silver’s band from Frank Sinatra, while drummer Roger Humphries was somewhat of a child prodigy who went on to play with Ray Charles after recording “Song”.

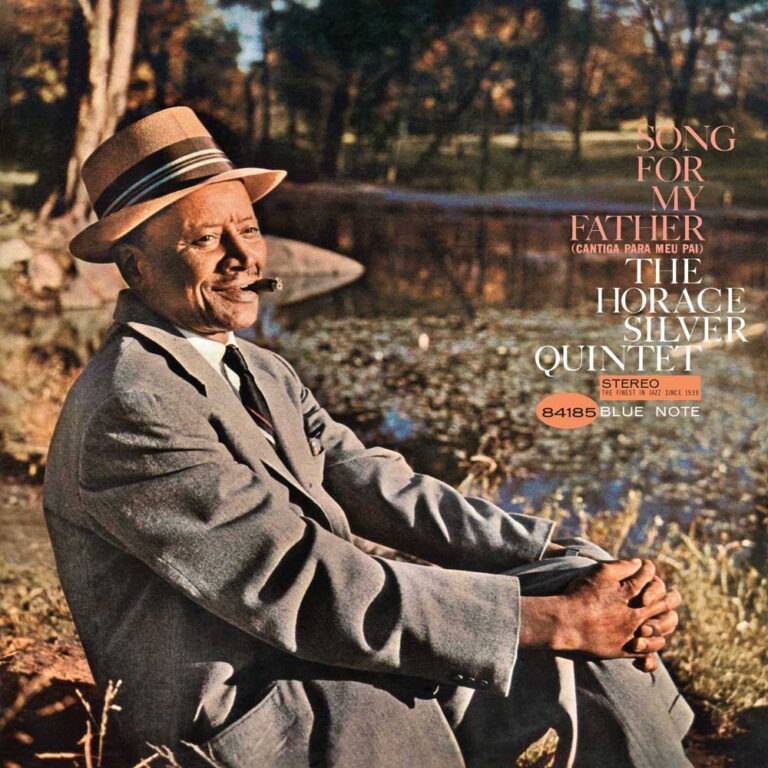

HORACE SILVER Song For My Father

Available to purchase from our US store.

The resplendent title track was influenced by the bossa nova craze of the early 1960s, but Silver later reported that its famous melody was “inspired by some very old Cape Verdean/Portuguese folk music” – his guitar-playing father hailed from Cape Verde, an island country in West Africa, and often involved Horace in family jam sessions. The tune features Silver’s irresistible chord vamps and memorable question-and-answer phrases – in his 2014 JazzTimes obituary of Horace, pianist Jason Moran said that “Song” was the first complete solo he ever learned.

Steely Dan fans will also recognise a distinct similarity between “Song” and “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number”. Fagen and Becker can probably count themselves lucky that Silver didn’t seek royalties – the Dan weren’t so fortunate with Keith Jarrett, who successfully sued them after picking up on (extremely tenuous) similarities between their 1980 song “Gaucho” and Jarrett’s composition “Long As You Know You’re Living Yours”.

Elsewhere, “The Natives Are Getting Restless” initially showcases Silver’s patented fast jazz/calypso feel before becoming a vehicle for wonderfully expressive solos from Jones and Henderson. “Calcutta Cutie” is a modal classic with especially creative drumming from Humphries, mainly using soft sticks. “Que Pasa” has a Spanish lilt, as its title suggests, and yet another catchy melody and harmonically-intriguing Silver solo, while Henderson’s “The Kicker” is simply a prime slice of bluesy post-bop with incredibly tight ensemble playing. The closing trio ballad “Lonely Woman” – not to be confused with Ornette Coleman’s famous tune of the same name – is deceptively simple, never quite going where you think it will.

Silver’s Blue Note career continued apace after “Song For My Father”, despite brushes with back trouble and a repetitive strain injury, and he also found time to mentor all-time greats such as the Brecker brothers and Billy Cobham. The album resonates through the years, and remains an absolute must-have for anyone even remotely interested in jazz.

Matt Phillips is a London-based writer and musician whose work has appeared in Jazzwise, Classic Pop, Record Collector and The Oldie. He’s the author of “John McLaughlin: From Miles & Mahavishnu To The 4th Dimension”.

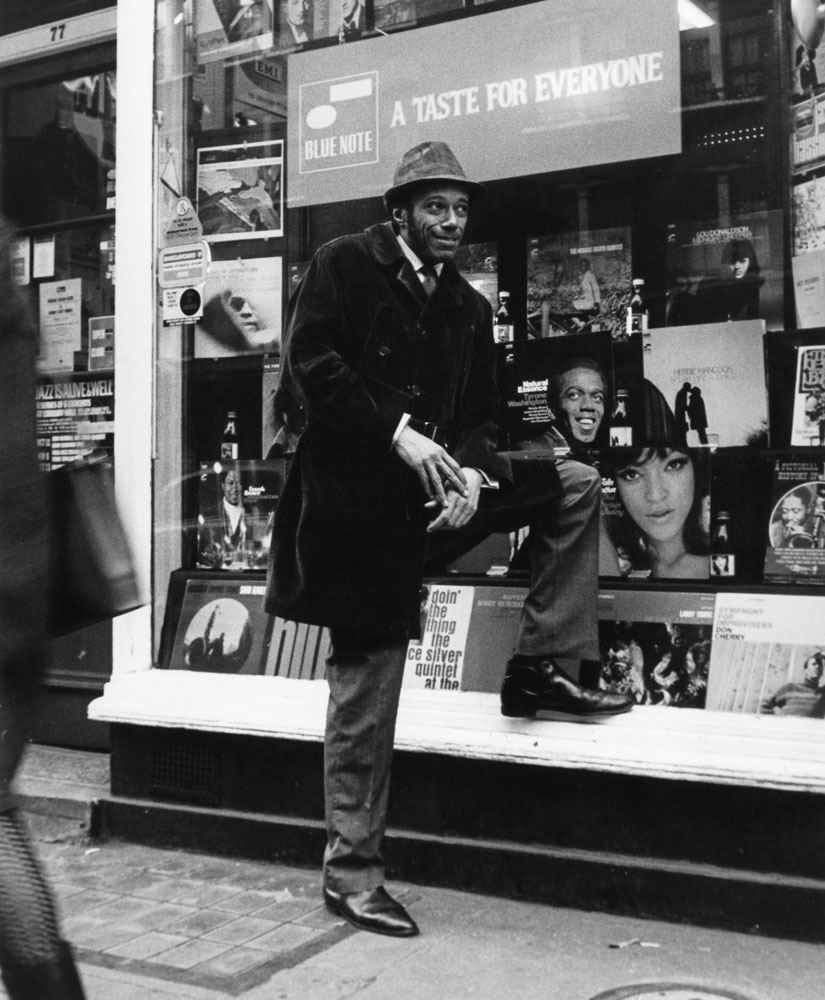

Header image: Horace Silver. Photo: David Redfern/Redferns.