My son, aged five, has made it fairly clear that he wants to learn how to play the piano. Actually, to be more accurate, he’s made it clear that he wants to own a piano, because he enjoys playing it, whether he’s learned how to or not.

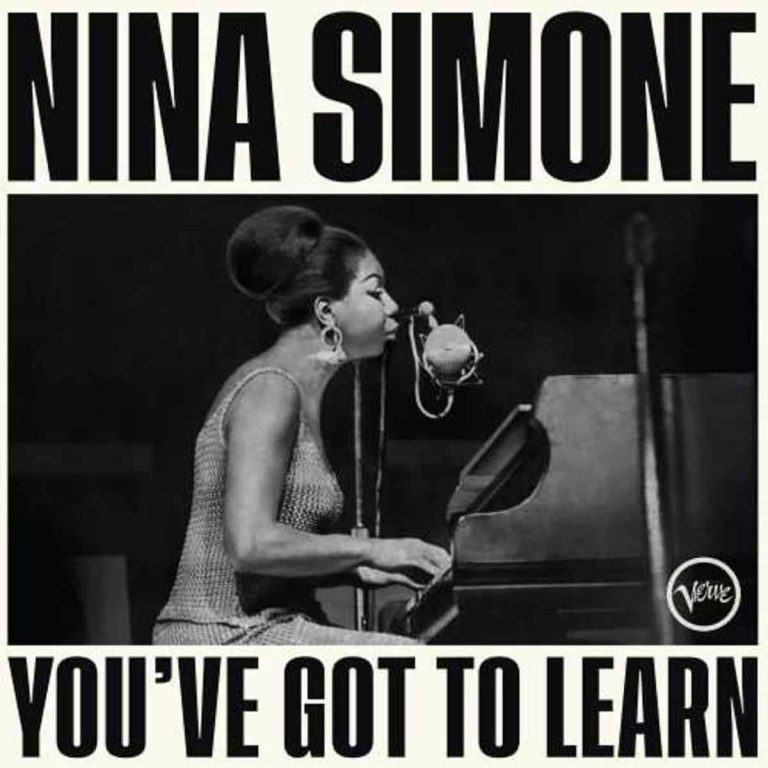

I’ve started this article about Nina Simone with an anecdote about my son because they share the same musical impulses, a couple of generations apart. The difference is that Nina Simone (born Eunice Kathleen Waymon in 1933) started her journey about two years earlier in her life than my budding pianist has. She started playing at the age of three, famously too little to even reach the pedals.

There were other barriers too; bigger ones that couldn’t be solved by simply growing taller over time. An early student of a classical repertoire, Nina’s aim was to become a renowned African-American classical pianist. And with those two first prefixes, African-American, we suddenly find ourselves facing racial tensions that three year-old Nina would have been blissfully unaware of.

It’s easy to define an artist like Nina Simone by what she wasn’t allowed to do, what she was denied, and the struggles she was forced to overcome. This is one of the many occupational hazards of being a black artist, of any discipline, in the modern western world. You can find yourself characterised by racism and race politics. At the same time, it would be naive to ignore these contexts. After years spent learning her craft, playing in churches and winning a one year scholarship at New York’s internationally renowned Juilliard School for the performing arts, Nina Simone still found herself hindered from progress by the colour of her skin. After being denied a scholarship to Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music, she later stated in an interview that she was refused ‘because I was black.’

Her blackness shines through the legacy of her work. In an important sense, she stands as a figure synonymous with black excellence: regal, powerful and poised. It’s hard to find a photograph of her that isn’t exuding a confidence that feels difficult to separate from her identity as a black woman, having grown and lived in an era of overt racism and discrimination.

It’s no accident and little surprise that by the 1960s, Nina had become active in the US Civil Rights movement, recording songs that become anthems for the cause. One example, “Mississippi Goddam,” was banned across parts of the US South for its unflinching critique of the racism common in the region, set to an upbeat, almost jaunty tune. The contradictions are fascinating – using popular music to define the experiences of black communities who were terrorised by state sponsored white supremacy.

And yet, Nina Simone has never been archetypal. One of her enduring hits, 1968’s “Ain’t Got No / I Got Life” is a glorious celebration of being your truest self and living your own life. The lyrics chant through a list of everything that makes you you, from your hair to your toes to your soul, alongside an exhilarating dismissal of all the things you might not have: be it wine, schooling or religion. It’s a powerfully universal idea: that the only person who gets to define you, is yourself – insecurities and contradictions in tow.

In many ways, Nina Simone pushed back against accepted norms. The music that made her popular leaned away from the Eurocentric conformity of a classical canon, towards a distinctly African-American heritage. Jazz, Blues, Soul… genres of music that are political by nature if not definition, challenging the status quo and centring black creative expression. In an important sense, Nina Simone is an emblem of this kind of political populism; simultaneously enigmatic and inviting.

Of course, her legacy lives on. If you examine hip hop, the biggest American cultural export of the 20th century, it’s not long until you find nods to Nina Simone and the black pride she represents. One resonant moment for me is in 1996’s “Ready Or Not” by the Fugees, where Lauryn Hill chastises so-called gangsta rappers for ‘imitating Al Capone’, asserting that she’ll ‘be Nina Simone’ instead. Then In 2017, Jay Z’s “The Story of OJ” employed a sample of Nina Simone’s “Four Women”, itself an essay into colourism, racism and the post-slavery stereotypes levelled at black American women.

The references might be subtle, but the depth of criticality and humanity in Nina Simone’s catalogue can be felt as well as heard, even if they aren’t academically understood. For many listeners, the song “My Baby Just Cares For Me” will be a stand-out, a jazz standard that Nina recorded for her debut album, “Little Girl Blue,” in 1957, that was then revitalised via a perfume advert in 1987. The song has a whimsical simplicity that speaks to the sociable, intimate side of jazz, one of the many tones that the artist could paint with sound.

Now, ninety years after her birth, Nina Simone remains a cultural figure deserving of critical attention and praise alike. But more than this, her music remains both resonant and relevant in an age where we’re still grappling with racial discrimination and black women continue to face the harsh intersections of racism and sexism. Here, Nina Simone will always be an example of how to illuminate dark places and turn social challenges into creative insight.

Jeffrey Boakye is an author, broadcaster and educator with a particular interest in issues surrounding race, masculinity, education and popular culture. He provides training for schools, universities and businesses, and co-hosts BBC Radio 4’s award-winning “Add to Playlist” programme.

Header image: Jack Robinson/Hulton Archive/Getty